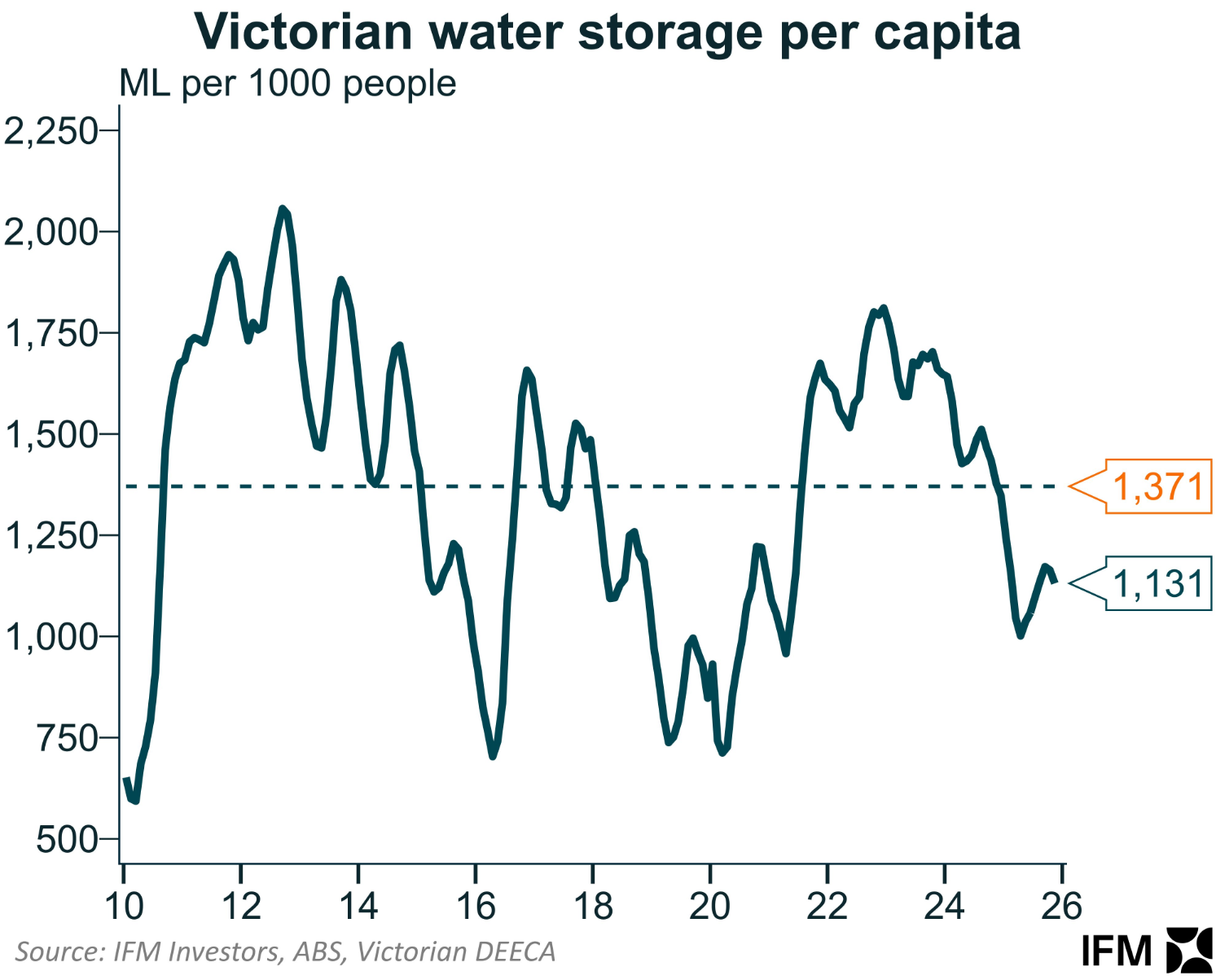

In late December, Melburnians were warned that they could soon face severe water restrictions following the steepest annual decline in water storage levels since the Millennium Drought.

Melbourne’s water storages dropped from 86% to 75.1% in a single year—a fall of 239 billion litres—and authorities urged conservation measures and planning for new water sources, such as desalination and recycling.

IFM Investors’ chief economist, Alex Joiner, likened Melbourne’s water predicament to the housing market, where talk is always about a lack of supply rather than pressures from excessive population growth.

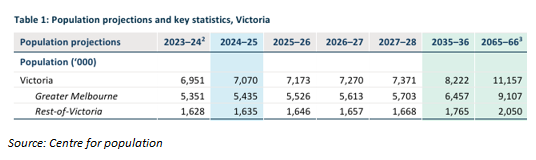

Melbourne’s population is projected by the Centre for Population to balloon by 3.7 million (67%) by 2065-66, which will place massive demands on the city’s water supplies.

To add further insult to injury, the Victorian Government has embarked on a plan to ramp up investment in data centres, which will require large amounts of energy and water for cooling.

Victoria’s Minister for Economic Growth and Jobs, Danny Pearson, has announced that the government will fast-track data centre investment.

“This is a race”, Pearson told the Australian Financial Review. “We’ve got to bring in the capital. We’ve got to make sure that we’ve got a really good investment climate here in Victoria, so they want to come here to set up shop, and let them innovate, let them come up with new products, new services, through super computing or through quantum computing”.

Pearson said:

- Victoria will not introduce new regulations or even a fast‑track approvals system, arguing the fast‑moving AI sector cannot wait 18 months for new processes.

- The state wants to create a “really good investment climate” to lure hyperscale data centres.

- Intervention will occur only if unforeseen negative consequences arise.

Victoria’s approach contrasts sharply with NSW, which is considering charging data centres for their heavy use of power and water to protect households from higher bills.

Melbourne’s Lord Mayor Nick Reece has called on the government to better manage the environmental impact of data centres, warning that proposed centres in Melbourne’s west could use up to 20 gigalitres of water a year—equivalent to 4% of the city’s total water—alongside significant amounts of energy.

“The rise in data centres is the biggest thing to hit our energy systems since the introduction of air conditioning in the 1950s”, Reece told the ABC.

“So we need to make sure we get this right in terms of energy consumption, in terms of water systems—and at the moment we don’t have the proper regulatory frameworks in place”.

The state government has scheduled the closure of the Yallourn coal power station in mid-2028 and Loy Yang A coal power station in 2035 in order to meet its legislated target to source 95% of the state’s electricity from renewable energy by 2035.

However, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) estimates that data centres will use 19% (14.1 terawatt hours) of Melbourne’s electricity grid by 2050, up from 2% in 2025.

The projected 67% increase in Melbourne’s population, the need for new energy-guzzling desalination plants to augment water supplies, and the state’s 50% electric vehicle target will also massively increase electricity demand.

Consequently, Melbourne’s energy and water systems are under threat.

Unless drastic policy action is taken on immigration, energy, and data centres, Victoria faces an energy- and water-scarce future.