The Pulse’s Ross Elliott has written an excellent article on the administrative bloat that has engulfed Australia’s planning industry.

Elliott notes that lawyers he has spoken with told him “they didn’t really know how many [planning-related] pages of rules and regulations were now in force—just that it would be so many as to be impossible to count”.

This complexity has led the Planning Institute of Australia to call for more town planners rather than calling for less red tape.

“The idea of a university-educated Town Planner with a HECs debt now devoting their mind to what are often mindless administrative processes seems a terrible waste of human intelligence”, argues Elliott.

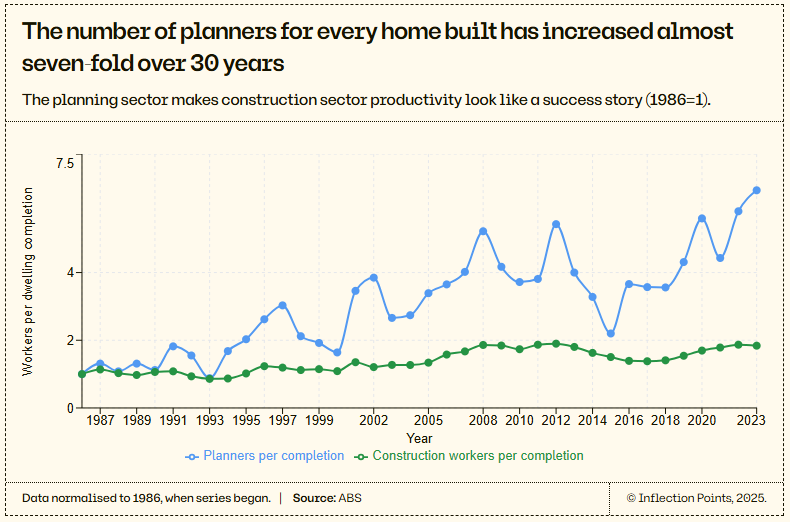

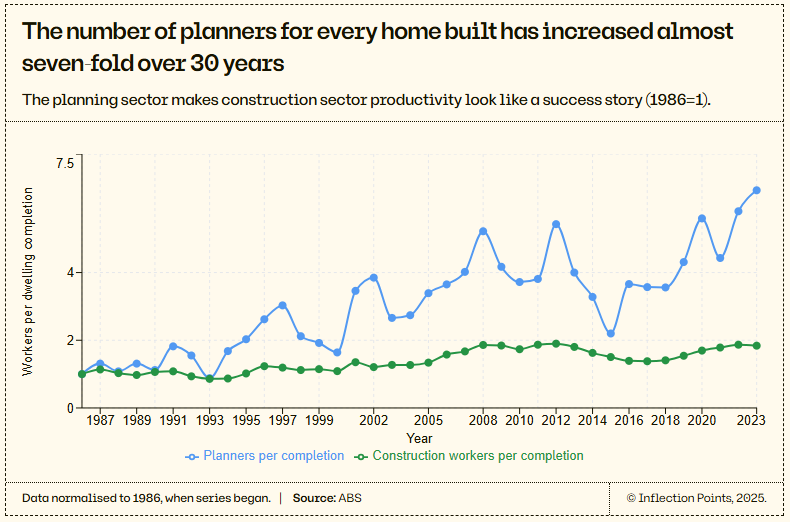

To highlight his point, Elliott posted the following chart from Jonathan O’Brien—founding editor-in-chief of Inflection Points—showing the explosion in the number of planners relative to construction workers over the past 30 years:

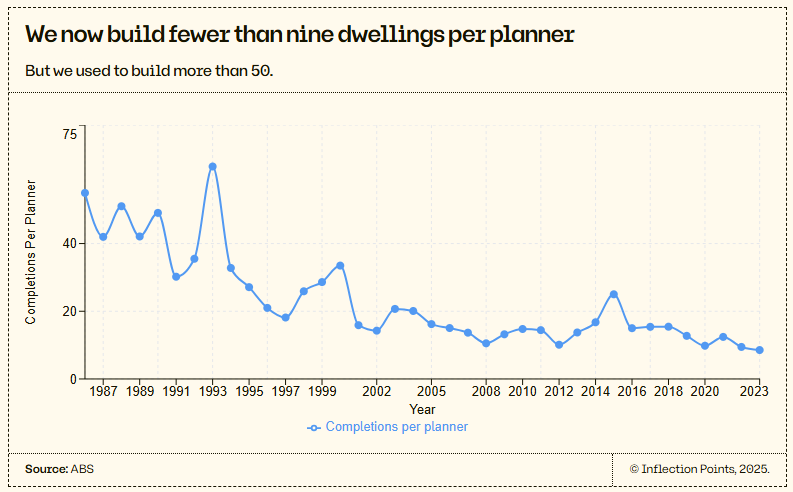

O’Brien also published the following chart showing that Australia is building far fewer homes per planner than it was 30 years ago:

Finally, O’Brien showed that Australia has experienced faster growth in planners than dwelling values:

Thus, the evidence clearly shows that administrative complexity has engulfed the planning industry, reducing productivity.

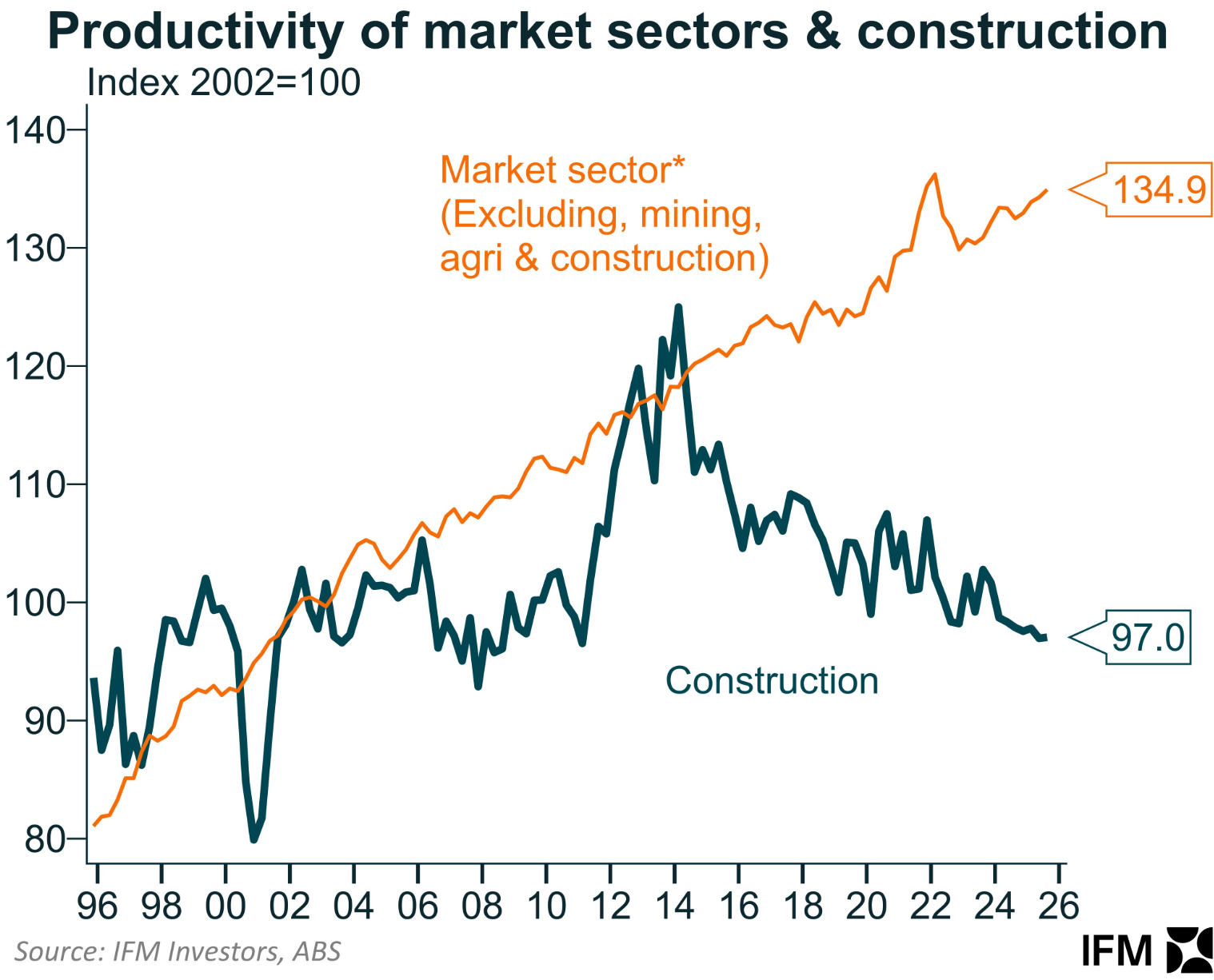

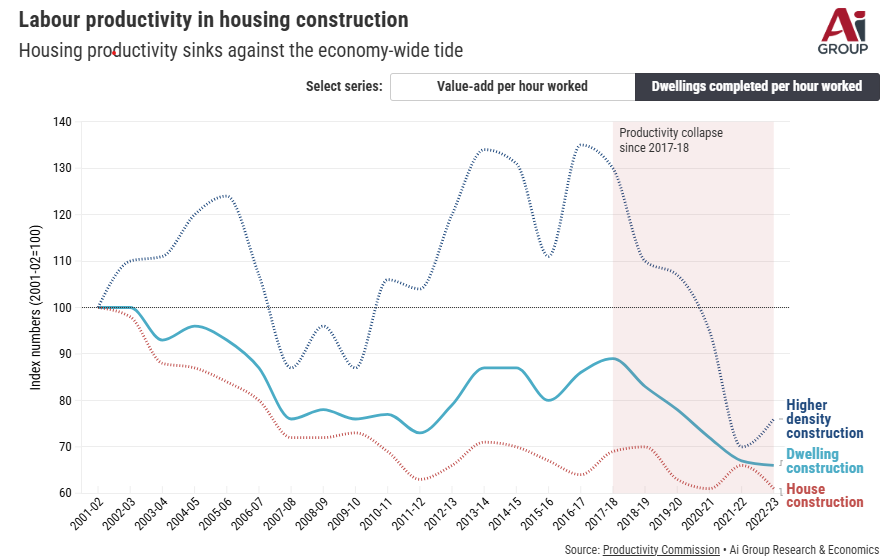

This administrative bloat extends to the broader construction sector, which has experienced a long-run collapse in construction sector productivity:

Chart by Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

A recent analysis by the Australian Industry Group showed a corresponding decline in the number of homes built per hour worked, reflecting lower productivity.

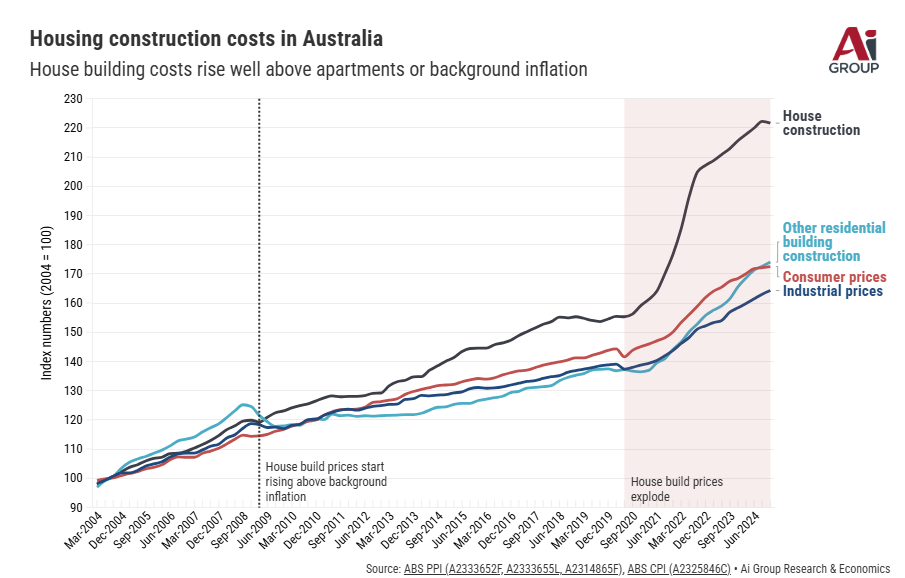

This decline in construction sector productivity has been accompanied by a surge in housing construction costs since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic:

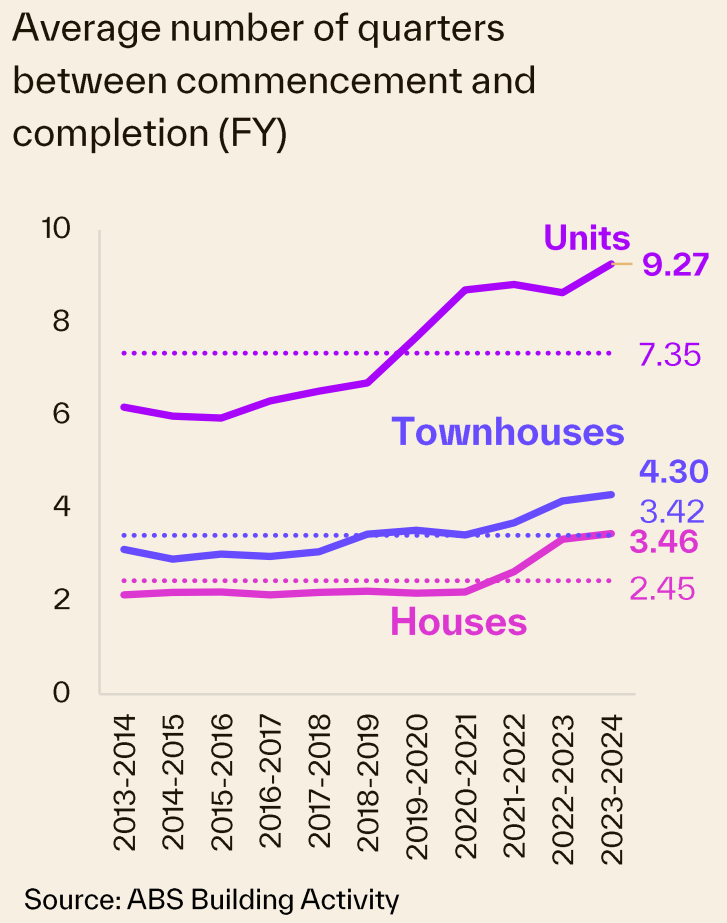

The average time to build new housing in Australia has also ballooned, as illustrated below by Cotality:

“Trying to extract more houses from an industry with declining productivity is like filling a bucket with a widening hole”, Australian Industry Group CEO Innes Willox said. “Without action to turn around this decade-long decline, Australia has little chance of meeting its targets, or ensuring affordable and secure housing for our changing population”.

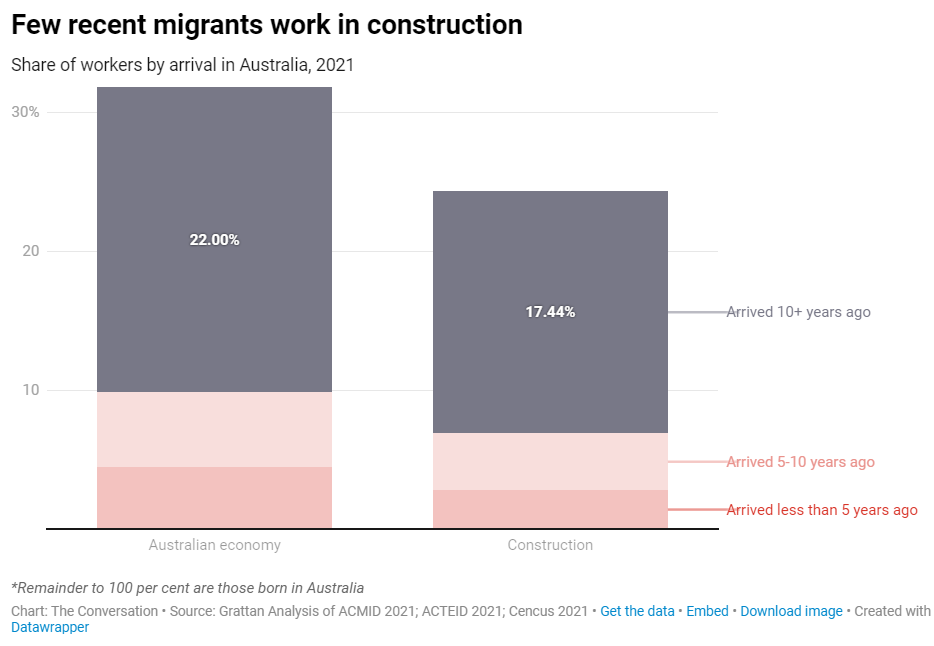

The situation is made worse by the fact that few migrants work in the construction sector.

“Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”, Grattan reported.

As a result, Australia’s migration program significantly increases demand for housing and infrastructure without boosting supply.

The Takeaway:

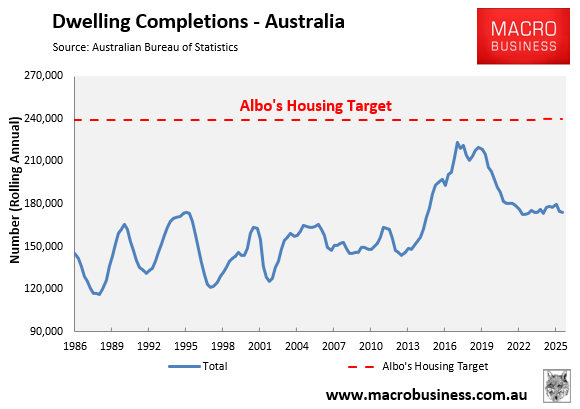

The Albanese government set a target to build 1.2 million homes over five years, requiring 240,000 homes to be built annually, starting from 1 July 2024.

However, as of the September quarter of 2025, only 219,000 dwellings had completed construction, 27% fewer than the 300,000 required run rate to meet the target.

Without significant improvements in productivity in the construction sector, Australia’s rate of housing construction will remain inadequate.

Australia needs to reduce administrative complexity and red tape, alongside running a smaller and better-targeted migration system.