Australia’s federal budget uses two main deficit measures, and they differ because they treat certain transactions differently—especially asset sales, loans, and off‑budget funds.

The headline balance captures all cash flows in and out of the Commonwealth government, including:

- day‑to‑day spending

- tax revenue

- capital spending

- asset purchases and sales

- loans issued and repaid

- equity injections

- transactions with government investment funds (e.g., Future Fund, CEFC, NAIF).

The headline budget balance shows the total change in the government’s cash position and can be volatile due to large transactions (e.g., equity injections into off‑budget funds).

The underlying balance receives most of the attention and excludes many large, lumpy, or non‑recurring financial transactions, such as Future Fund earnings

- student loan repayments

- equity injections

- loans to government businesses

- asset sales

- investments in off‑budget funds

- net Future Fund contributions.

The underlying balance is the difference between recurrent spending and recurrent revenue, and is what most economists, the Treasury, the RBA, and ratings agencies focus on.

In short, the headline deficit counts everything, including loans and asset purchases, whereas the underlying deficit strips out those financial transactions to show the government’s real operating position.

The Problem:

The gap between the two measures has blown out because the federal government has increasingly pushed spending off the balance sheet via:

- off‑budget investment vehicles

- special funds

- equity injections

- government loans

As a result, the headline deficit has ballooned relative to the underlying deficit.

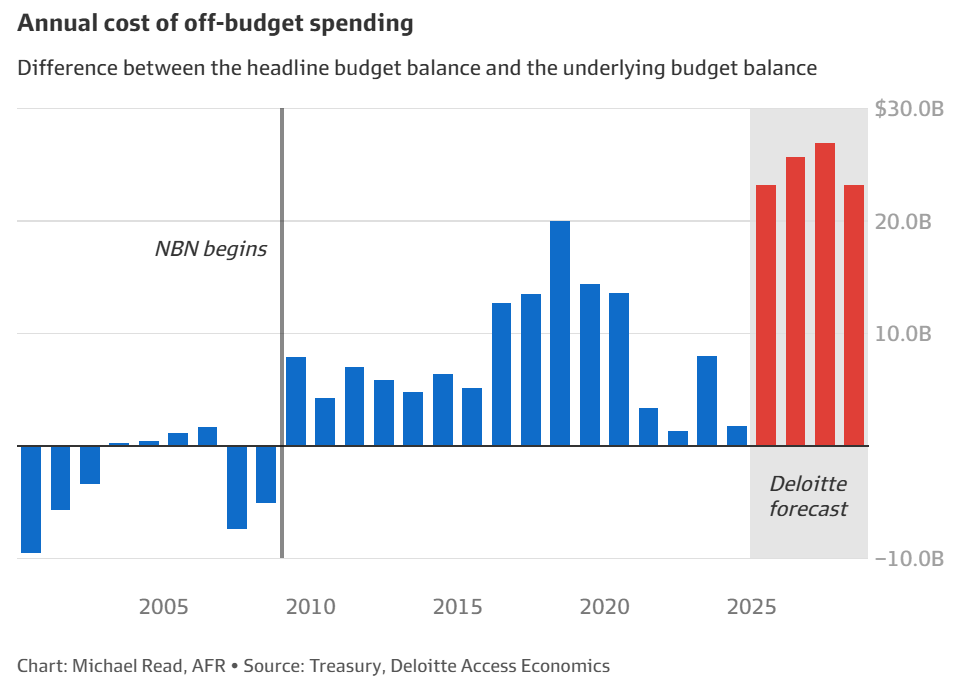

The following chart from The Australian Financial Review illustrates the expansion in “off-budget” spending by the federal government.

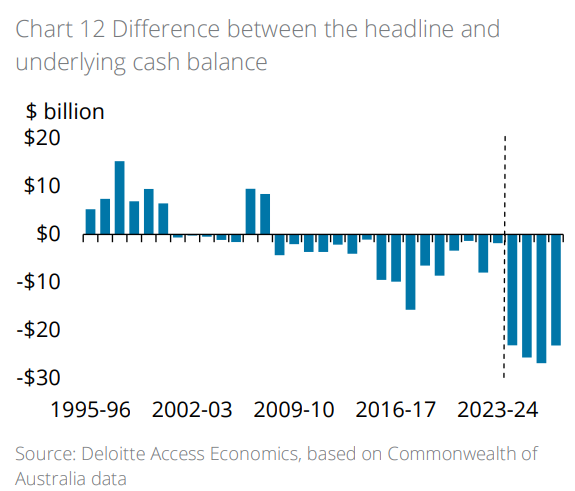

Last year, Deloitte produced the following chart showing the growing gap between the headline and underlying budget balance:

The growth in off-budget spending obscures the true state of the federal government’s finances, fuels inflation, and reduces transparency and scrutiny of spending programs.

“All these tricks obscure the debate around Australia’s long-term fiscal outlook and detract from an honest conversation about the fiscal challenge”, noted Deloitte Access Economics partner Stephen Smith.

“This is just a sleight of hand, as while it doesn’t show up in the budget deficit, it adds to public debt. Hardly consistent with [the charter of budget honesty”, added AMP chief economist Shane Oliver.

With Commonwealth debt approaching $1 trillion, Dimitri Burshtein has called on the federal government to wind up the spurious network of government‑run financial vehicles that borrow heavily and invest in markets under the banner of “nation‑building” or “future funds”.

Writing in The Australian newspaper, Burshtein noted that more than $400 billion—roughly 40% of Commonwealth debt—is tied up in government investment funds and special vehicles. He labelled them “leveraged bureaucratic playthings” that allow governments to speculate with borrowed money:

The commonwealth now operates seven Future Funds and eight Special Investment Vehicles, overseeing more than $400bn of public capital. At the same time, with federal debt closing in on $1 trillion, interest costs are now the fastest-growing item in the budget; rising faster than the NDIS, childcare, and defence, and far faster than the economy itself.

The alphabet soup of this fiscal melange includes the FF, CEFC, NRFC, HAFF, NAIF, AIFFP, ARENA, RIC, MRFF and DRF.

Strip away the branding and these entities are simply leveraged investment vehicles operating on the government’s balance sheet. Unlike private funds, however, their managers put no personal capital at risk. Instead, they enjoy generous taxpayer-funded salaries and one-way incentives: bonuses for gains, while losses are quietly socialised.

Burshtein called on the government to liquidate these funds to pay down debt, reduce interest costs, and free fiscal space for productivity-enhancing tax reform:

“Households are being squeezed by higher taxes, higher interest rates and falling real incomes while Canberra borrows ever more to play investor with other people’s money”.

“Every dollar locked away off budget is a dollar not used to pay down debt, relieve bracket creep, or reward work and enterprise”.

Burshtein argued that unless “fiscal seriousness returns”, Australians will continue to become poorer while the government pretends to invest in the future.

The Takeaway:

Tighter controls are required on government spending, and transparency is desperately needed regarding the various off-balance-sheet slush funds utilised by the government.

In addition to cutting wasteful and inefficient spending, the federal government should revisit the 2010 Henry Tax Review and initiate a fundamental tax reform process.

We must broaden the tax base beyond personal income and corporate taxes by expanding taxes on consumption, resources, and land.

Otherwise, Australia’s shrinking pool of workers will be taxed into oblivion.