Last year, I claimed that the Australian Treasury’s modelling of Labor’s 5% deposit scheme for first home buyers demonstrated that the Treasury had become the federal government’s propaganda arm.

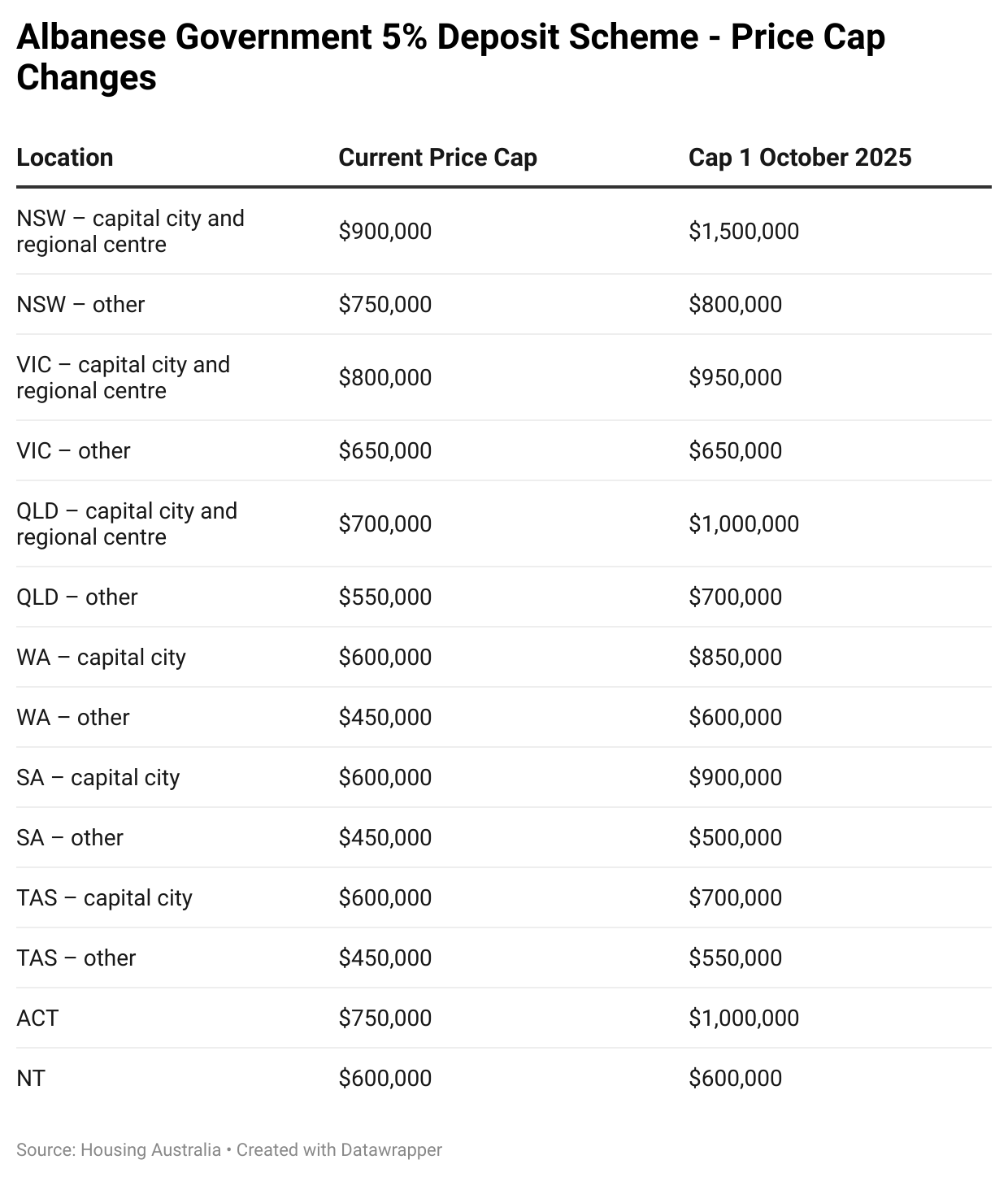

Labor’s First Home Buyer Guarantee program, which went into effect in October 2025, allows nearly all first home buyers to purchase a property with only a 5% deposit and no lenders’ mortgage insurance because taxpayers will guarantee 15% of the mortgage.

The Treasury’s analysis of the scheme, released prior to its introduction, forecast that the policy would only increase home values by 0.6% over six years.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Housing Minister Clare O’Neil used this modelling to deflect allegations that the policy would make housing less affordable by increasing home prices.

No analyst truly believed Treasury’s model.

For example, Lateral Economics anticipated that the 5% deposit scheme would increase national property values by 3.5% to 6.6% in 2026 and for several years afterwards.

Property prices were also forecast by Lateral Economics to increase by 5.3% to 9.9% in areas targeted by first home buyers, who fall below the scheme’s generous price caps.

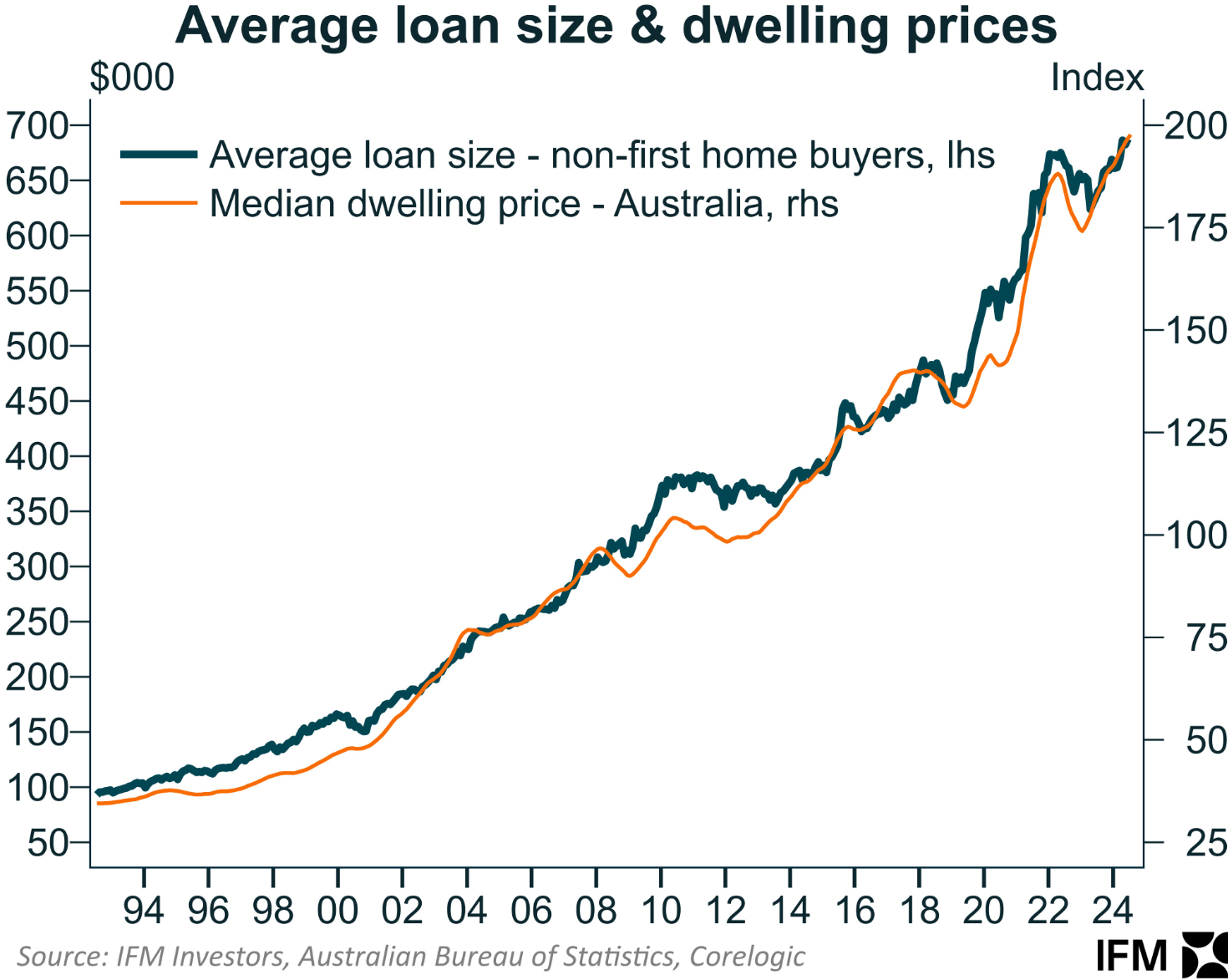

The 5% deposit program, like every other demand-side policy stimulus introduced in the last 25 years, will inevitably be capitalised into higher prices and larger mortgages, making the policy self-defeating in terms of affordability.

With this background in mind, internal Treasury documents cited by The Australian newspaper reveal that Labor’s expansion of the First Home Buyer Guarantee was expected to create “demand shocks” that would push up home prices more in the short term than the 0.6% over six years that the government publicly stated.

Treasury clarified that this figure averaged out 10 years of demand shocks and that short‑term effects would be significantly higher.

The first year alone was expected to see demand more than 30% above normal levels.

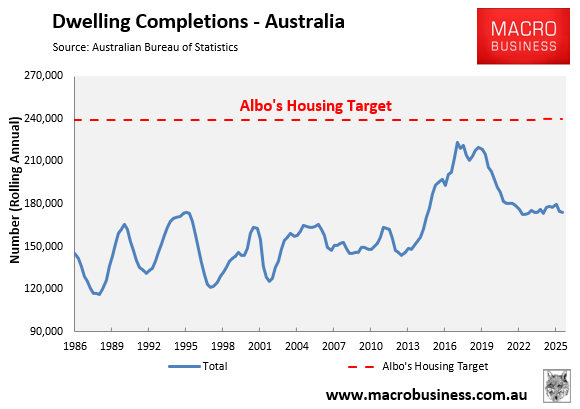

To prevent price rises, Treasury estimated Australia would need:

- 18,560 additional homes in the first year, and

- 3,524 extra homes each year after.

However, actual dwelling completion rates have fallen, meaning the anticipated supply increases have not materialised.

Several analysts argue the First Home Buyer Guarantee scheme boosts demand without increasing supply, making housing less affordable.

Peter Tulip from the Centre for Independent Studies told The Australian newspaper that early evidence shows price effects “substantially greater” than Treasury’s estimate, and claims that the scheme worsens the housing crisis because it does not address supply.

Cotality research director Tim Lawless noted stronger price growth in homes under the scheme’s price caps. That is, 3.6% growth for eligible homes versus 2.4% for ineligible ones in the December quarter.

Lawless believes the scheme has not improved affordability and has likely made it worse. He also warned that first‑home buyers in the coming year will face even higher prices.

“I can’t think of anybody that would think it’s improved housing affordability”, Lawless told The Australian newspaper.

“This is a demand-side stimulus that I guess the objective was to boost home ownership”.

“And if that’s the case, it’s probably had a short-term effect on achieving that objective. But if you’re a first homebuyer, say in October this year—a year down the track—it’s just going to be all the harder to access the marketplace because prices have been pushed higher in the price points that you’re looking in”.

“It’s not done anything for affordability apart from probably making it worse”, Lawless said.

The Treasury’s 0.6% price impact over six years would only be realised if prices corrected drastically lower after the initial price rise.

However, in this scenario, recent first home buyers would be driven into negative equity, with taxpayers bearing the brunt of any subsequent mortgage defaults.

Furthermore, the federal government will be incentivised to pursue policies that favour growing housing values because it has encouraged first home buyers to enter the market with low deposits and guaranteed 15% of their mortgages.

This puts Australia’s housing market at risk of becoming even more state-sponsored and supported than it already is.