Melbourne’s water storages have recorded their steepest annual decline since the Millennium Drought, driven by extreme dryness, record‑low inflows, and rising household demand.

Melbourne’s storages dropped from 86% to 75.1% in a single year—a fall of 239 billion litres.

Inflows from July 2024 to June 2025 were 36% below the 30‑year average, with January–June inflows being the lowest on record.

Daily household water use rose to 169 litres per person, up from 163 litres the year before. Melbourne also added some 38,000 new households, increasing pressure on the system.

Authorities are urging conservation and planning for new water sources (e.g., desalination and recycling).

“Melburnians have always adapted in dry times, and we need to do that again now”, said Yarra Valley Water Managing Director, Natalie Foeng, speaking on behalf of Melbourne’s water corporations.

“Our storages are secure today, but this year’s sharp fall shows how quickly they can drop in dry conditions and when rainfall is low. By using water wisely now, we can avoid or delay restrictions and protect supplies for our growing city”.

The reality is that Melbourne faces permanent water shortages amid rapid population growth, explosive growth in data centres, and possible reduced long-term rainfall.

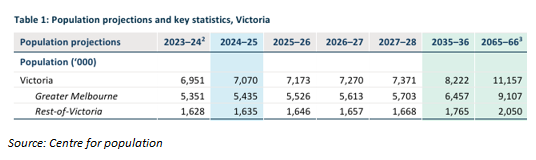

Population growth is sharply increasing household water demand. The 2025 Population Statement from the Centre for Population projected that Melbourne’s population would balloon by 3.6 million (65%) over the 40 years to 2065-66, driven by net overseas migration of 2.6 million:

Given that migrants having children also drives natural increase (i.e., births minus deaths) and that Melbourne’s birth rate is well below replacement, net overseas migration will be responsible for all of the city’s future population growth.

Having 65% more people living in Melbourne implies 65% more household demand for water. Where will the extra water supplies come from and how much will they cost?

Data centres, which require large volumes of potable water for cooling, are also expanding rapidly and consuming a growing share of Melbourne’s supply.

Last year, it was reported that Greater Western Water was reviewing 19 applications from data centres that would collectively consume almost 19 billion litres of water per year – equivalent to the annual usage of 330,000 Melburnians.

Saul Kavonic, head of energy research at MST Maquarie, said the sudden water demand from data centres had caught state governments “on the back foot”.

“Policy makers appear to have not adequately planned for rising water demand from population growth, let alone new demand from data centres”, Kavonic told news.com.au.

“Limitations on water availability are seeing data centres resort to using more electricity for cooling instead, shifting more of the burden on our limited water supply onto our fragile electricity grid”.

“This is not sustainable”, Kavonic said.

Desalination is also costly and energy-intensive, demanding large amounts of electricity from a grid that would already be stretched once the data centres were complete.

The upshot is that Melbourne is rapidly approaching a critical supply threshold, as demand surges faster than the water authorities can sustainably handle.

If the federal government had any sense (which it doesn’t), it would dramatically cut immigration so that water supplies (let alone housing and infrastructure) can keep pace with demand.

Big Australia immigration is literally a recipe for endless shortages, rising costs, and lower living standards.