In 2024, The Age reported the YIMBY (‘Yes In My Backyard’) manifesto as follows:

“Key to the YIMBY manifesto is the idea that a restrictive planning system, including existing height and heritage controls, is blocking a potential deluge of apartment construction in inner and middle Melbourne that – if allowed – would force down prices and rents”.

The YIMBY’s argument is that if planning systems were relaxed to allow more high-density apartments to be built anywhere, then home prices and rents would be forced lower by the resultant supply.

While the argument has superficial appeal, the actual economics of development get in the way.

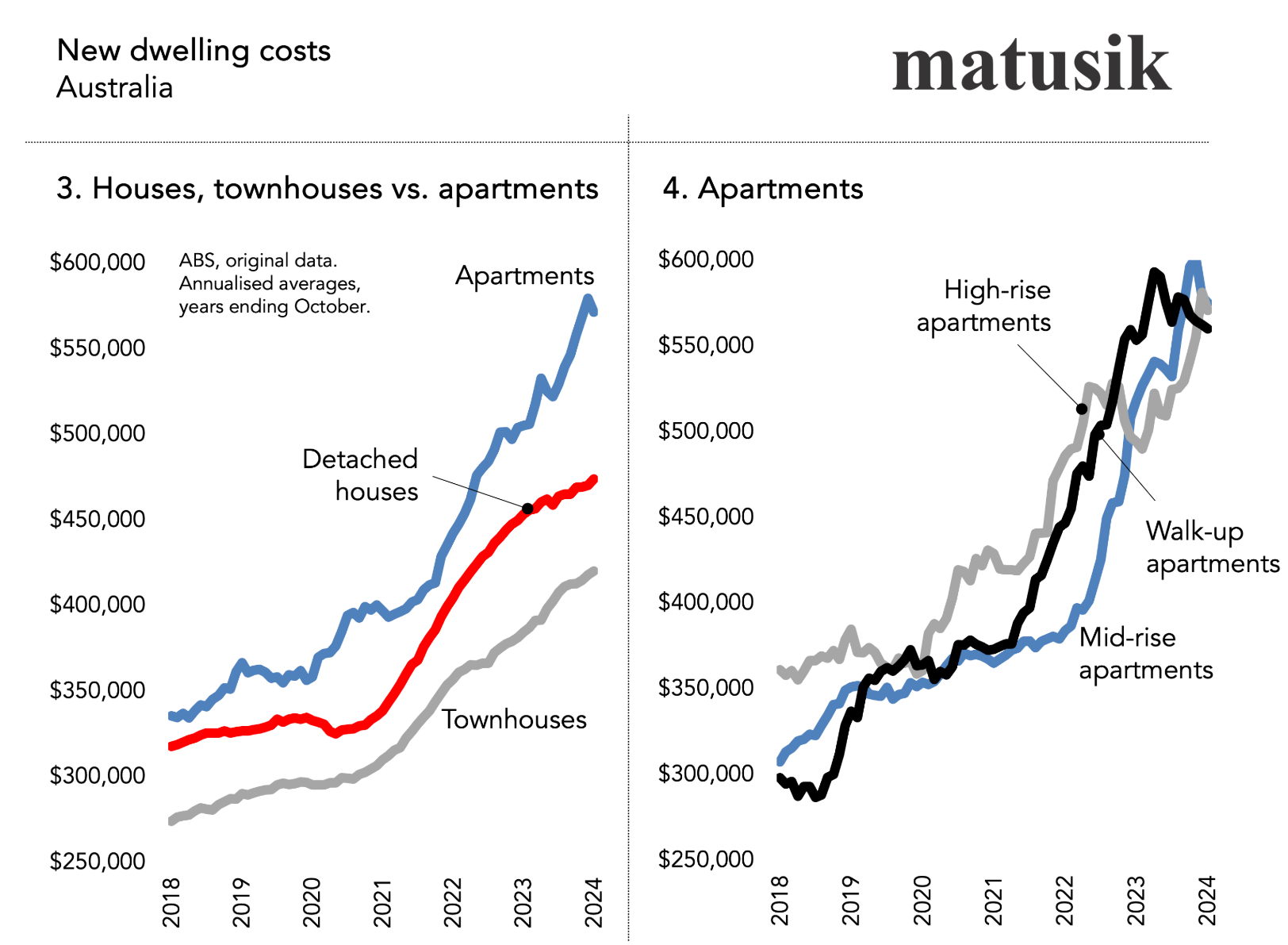

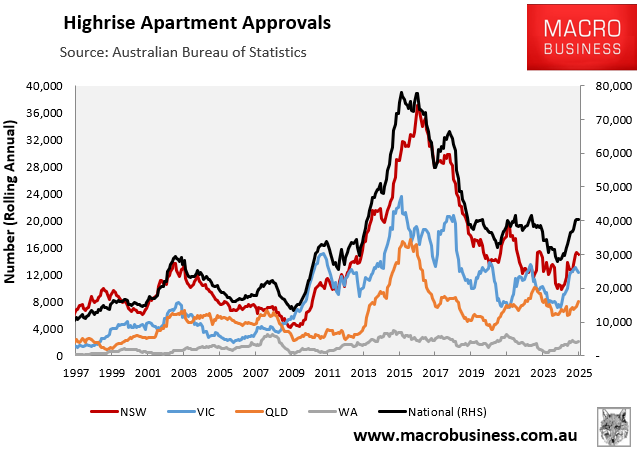

First, the cost of building apartments is exorbitant, as Michael Matusik illustrates below. This means that apartments cannot be delivered at a reasonable cost to buyers. Therefore, apartment construction rates will remain stillborn and won’t improve affordability.

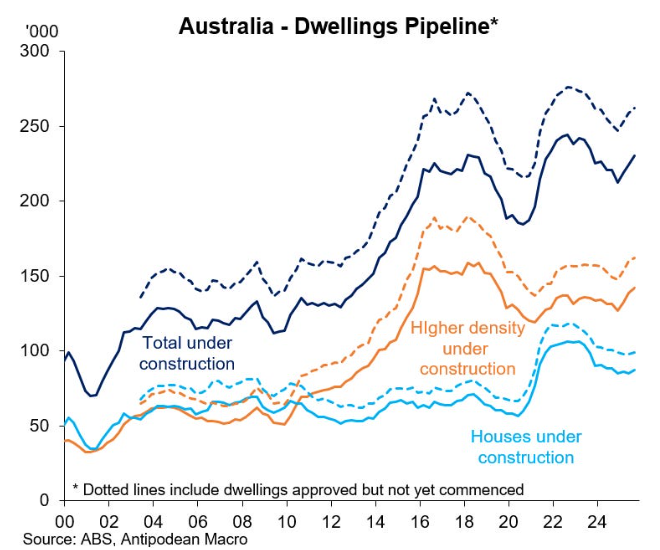

Second, Australia’s homebuilding industry is stretched to capacity, bulging with homes that have been approved for construction but not yet built. This means that any extra approvals will merely be added to the already bulging backlog of work to be done:

As illustrated above by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, “the pipeline of unfinished/unbuilt dwellings in Australia increased further in Q3 2025, with 230k dwellings under construction and a further 32k homes approved but not yet commenced”.

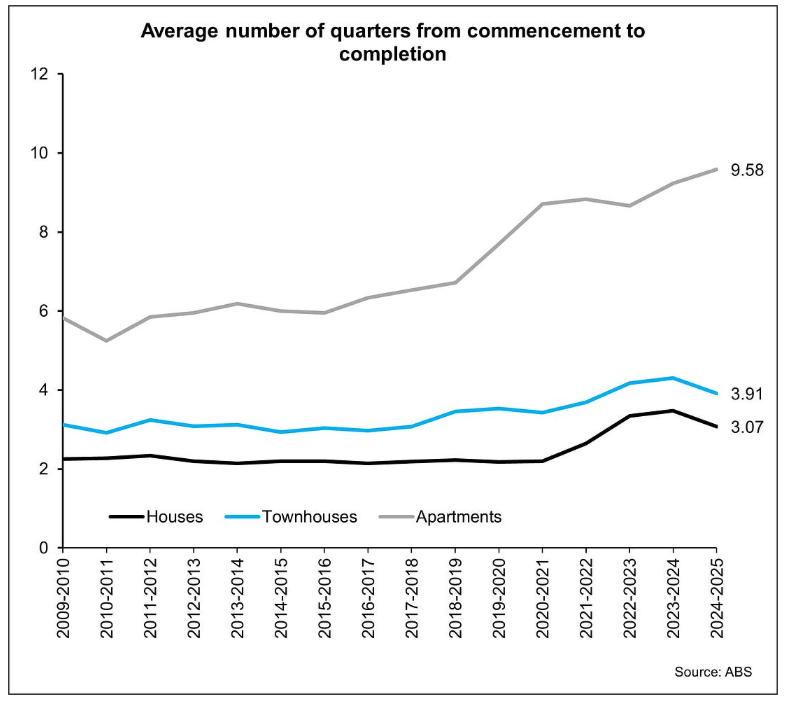

In a similar vein, the time taken to build housing has also ballooned, further emphasising that the homebuilding industry is stretched to the limit:

Thus, without a significant increase in capacity, adding more approvals to the backlog will result in the pipeline swelling, rather than homes actually being built.

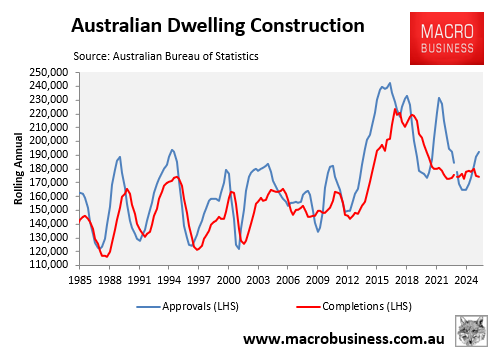

This is precicely what has happened since the pandemic. In the five years to September 2025, there were 957,600 dwellings approved for construction but only 879,900 dwellings completed, a difference of 8.2%:

The reality is that there are sound economic reasons why Australia’s housing construction system has become constipated, unable to lift supply to meet demand. Factors include:

- Structurally higher interest rates.

- Structurally higher construction costs.

- Structurally higher residential lot costs.

- Government infrastructure projects have exacerbated construction sector labour shortages.

- High insolvency rates in the construction sector.

Even if it were magically possible to lift construction rates to record levels, would it be desirable?

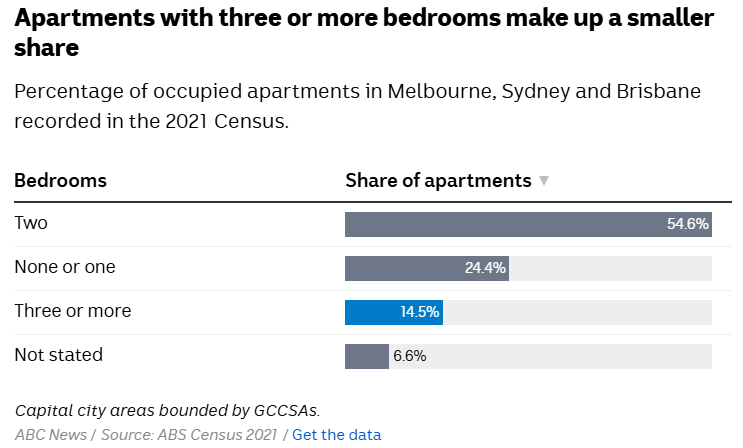

The 2015 to 2019 housing construction boom was driven by the mass building of high-rise apartments, many of which were low quality and defective and have exorbitant strata fees.

The bulk of the apartments that were built were also the shoebox variety, totally unsuitable for raising children:

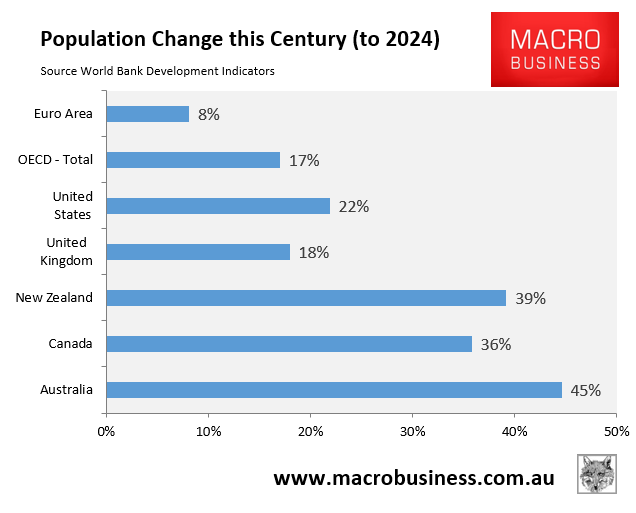

Instead of focussing on the planning bogeyman with the mistaken notion that it will boost supply, policymakers should moderate Australia’s rapid population growth to a level that aligns with the availability of housing and infrastructure.

Australian cities would not need to transform into slums of poor-quality high-rise shoeboxes if the federal government did not expand the population so aggressively via immigration.

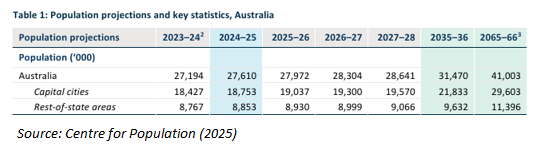

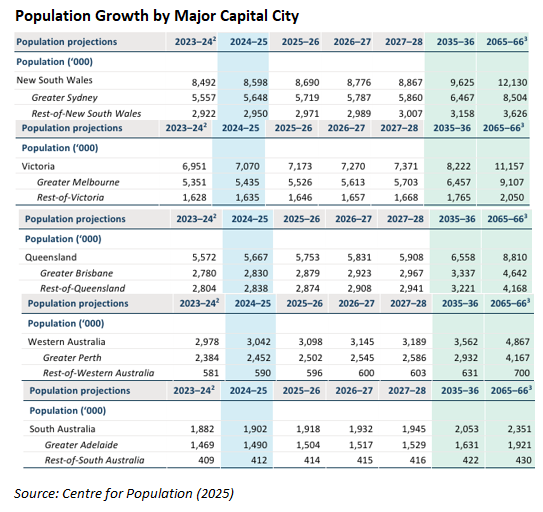

Sadly, the latest projections from Treasury’s Centre for Population suggest that Australia’s major cities will transform into high-rise slums, with the capital city population projected to expand by 10,850,000 (58%) over the 41 years to 2065-66:

This extreme population expansion will transform Melbourne (9.1 million) and Sydney (8.5 million) into mega-cities:

Who wants this outcome? Who voted for it? Answer: nobody.