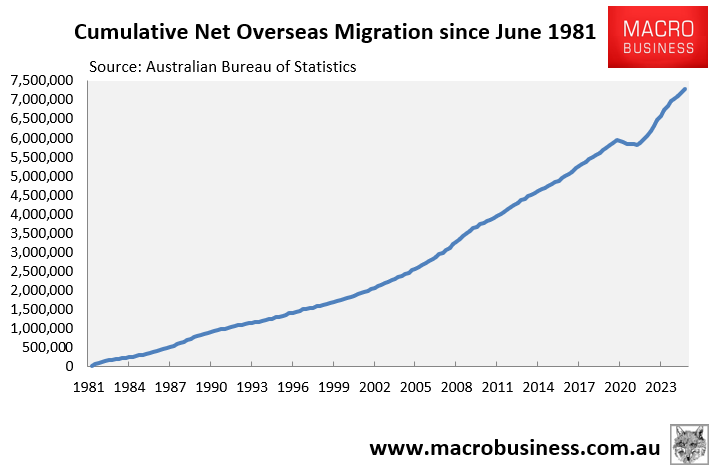

In mid-2023, just as Australia’s net overseas migration was ramping up toward record levels, the mouthpiece of big business, The AFR Chanticleer, proclaimed that Australian businesses were “licking their lips” at the prospect of higher migration, “with few doubting that a bigger Australia is better”.

“It is boosting retailers’ sales, increasing landlords’ ability to collect rent, helping miners and contractors find staff, bolstering the big four banks’ customer numbers, lifting pathology providers’ testing volumes, filling up Macquarie’s IT department”, the AFR Chanticleer wrote.

“You name it, chief executives are talking about it. For a lot of them, migration is the new growth”.

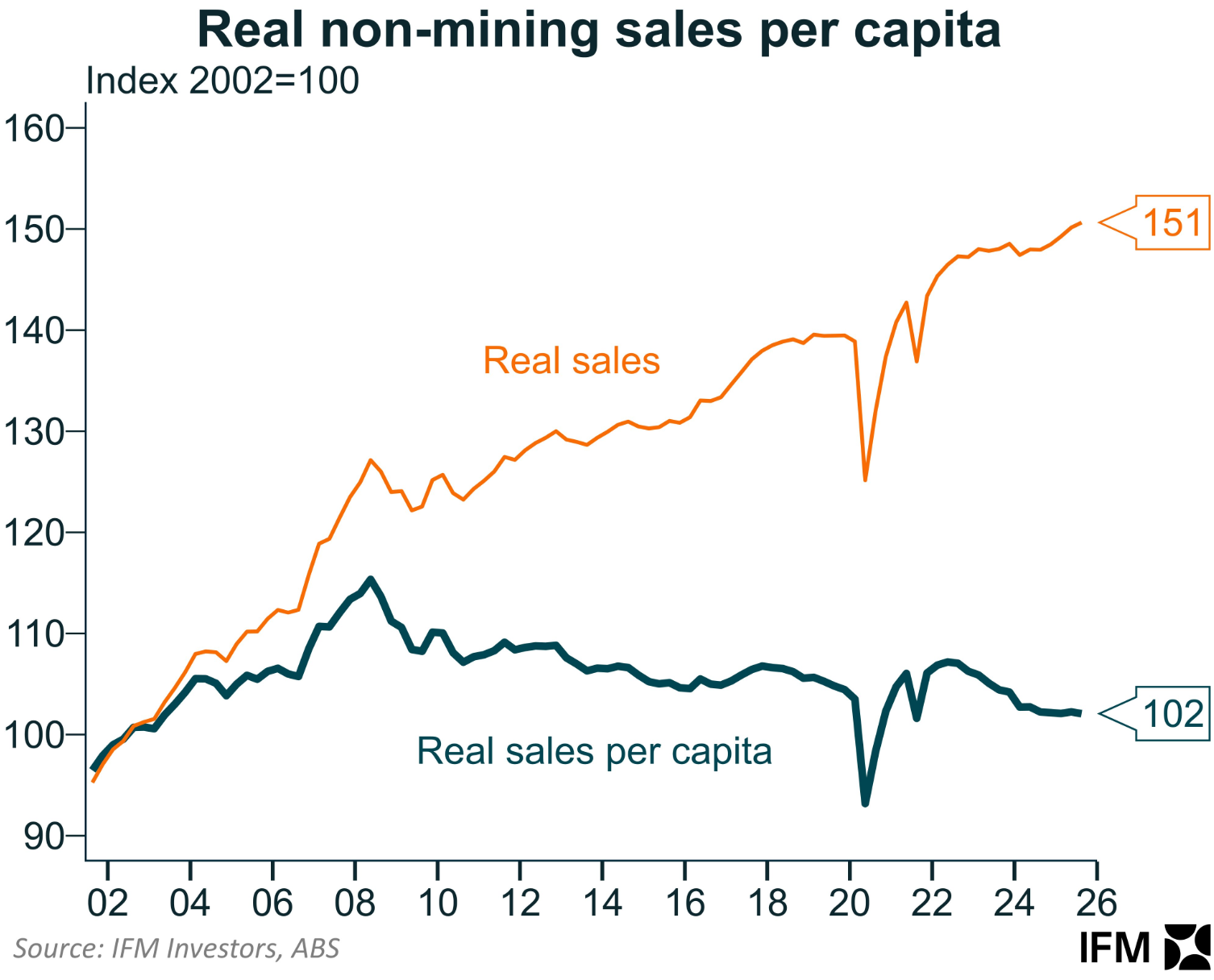

On Tuesday, Alex Joiner, the chief economist at IFM Investors, published the following chart on Twitter (X) showing how real non-mining sales of goods and services in Australia have grown by 51% since 2002. However, when adjusted for population growth, real sales have remained flat, growing by just 2% since 2002:

“A key political agenda to maintain population growth is unambiguously support the interests of big business first and foremost”, Joiner wrote in relation to the above chart.

Indeed, Australian real corporate sales revenue would barely have grown and profits would be far lower without the strong and continuous influx of migrants into Australia, which accelerated from the mid-2000s.

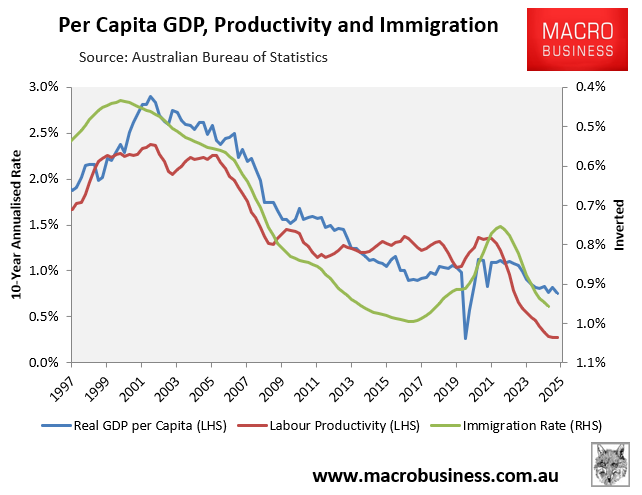

Meanwhile, labour productivity and per capita growth have collapsed alongside the surge in immigration:

The economy’s dependence on immigration, rather than productivity growth, has piqued the interest of Martin Conlon, head of Australian equities at Schroders, who is “betting against Australia’s great Ponzi scheme”—i.e., the economy’s unsustainable mix of high house prices and immigration:

An economy driven by, and dependent on, very high house prices that are supported by what Conlon says are unsustainable levels of immigration, is not healthy, and cannot last in the long term.

“It’s easy to stand back and say, oh, don’t worry, we can keep on importing people to hold up a Ponzi scheme. No one’s ever been able to hold up a Ponzi scheme forever,” Conlon says. “Affordability has to matter, global competitiveness of wages has to matter. It gets more dangerous when you move a long way away from sustainable policy”.

Conlon is seeking to short companies and sectors exposed to housing growth, such as banks heavily reliant on mortgage lending and developers and property-linked businesses.

While his view about Australia’s Ponzi economy is certainly correct, Conlon’s contrarian stance is risky because government policy often intervenes to support housing. Mass immigration is also used by policymakers as a growth driver.

However, Conlon argues that high debt levels and affordability constraints will eventually force a correction.

Private businesses like toll road operators, retailers, banks, property developers, and education providers love mass immigration because they get to enjoy the easy growth in revenue and profits that comes from an ever-expanding customer base.

Meanwhile, households suffer from the increased competition and reduced bargaining power at work, rising housing costs, rising infrastructure costs, a degraded environment, and longer and more expensive commutes.

The hidden costs of a ‘Big Australia’ essentially consist of massive private taxes, which the government conveniently ignores.

Now the Albanese government is doubling down on this junk policy by attempting to push immigration higher.