Employers now find it much easier to find workers, particularly those with lower skill levels, according to the most recent recruitment data from Jobs & Skills Australia.

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo of Antipodean Macro, the percentage of workers reporting difficulty obtaining employment has returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Lower-skilled workers are plentiful, whereas higher-skilled workers are relatively harder for employers to find. However, both lower-skilled and higher-skilled workers are experiencing recruitment difficulties that are consistent with pre-pandemic levels.

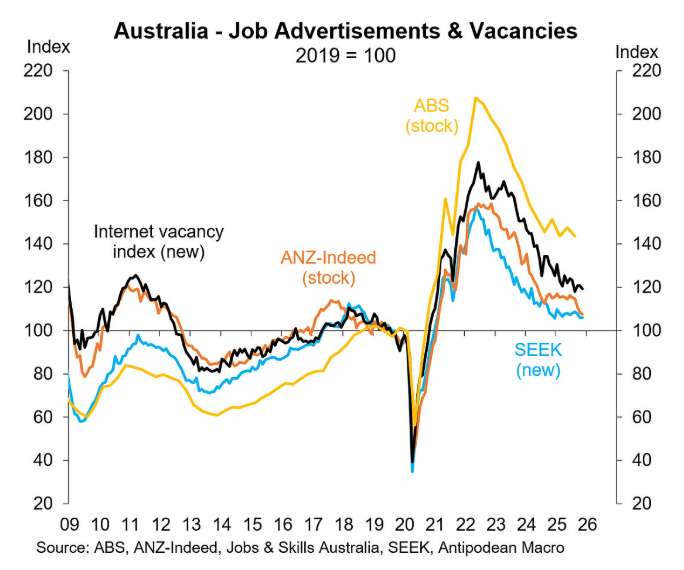

The decline in recruitment difficulty has followed a commensurate fall in job ads and job vacancies toward pre-pandemic levels:

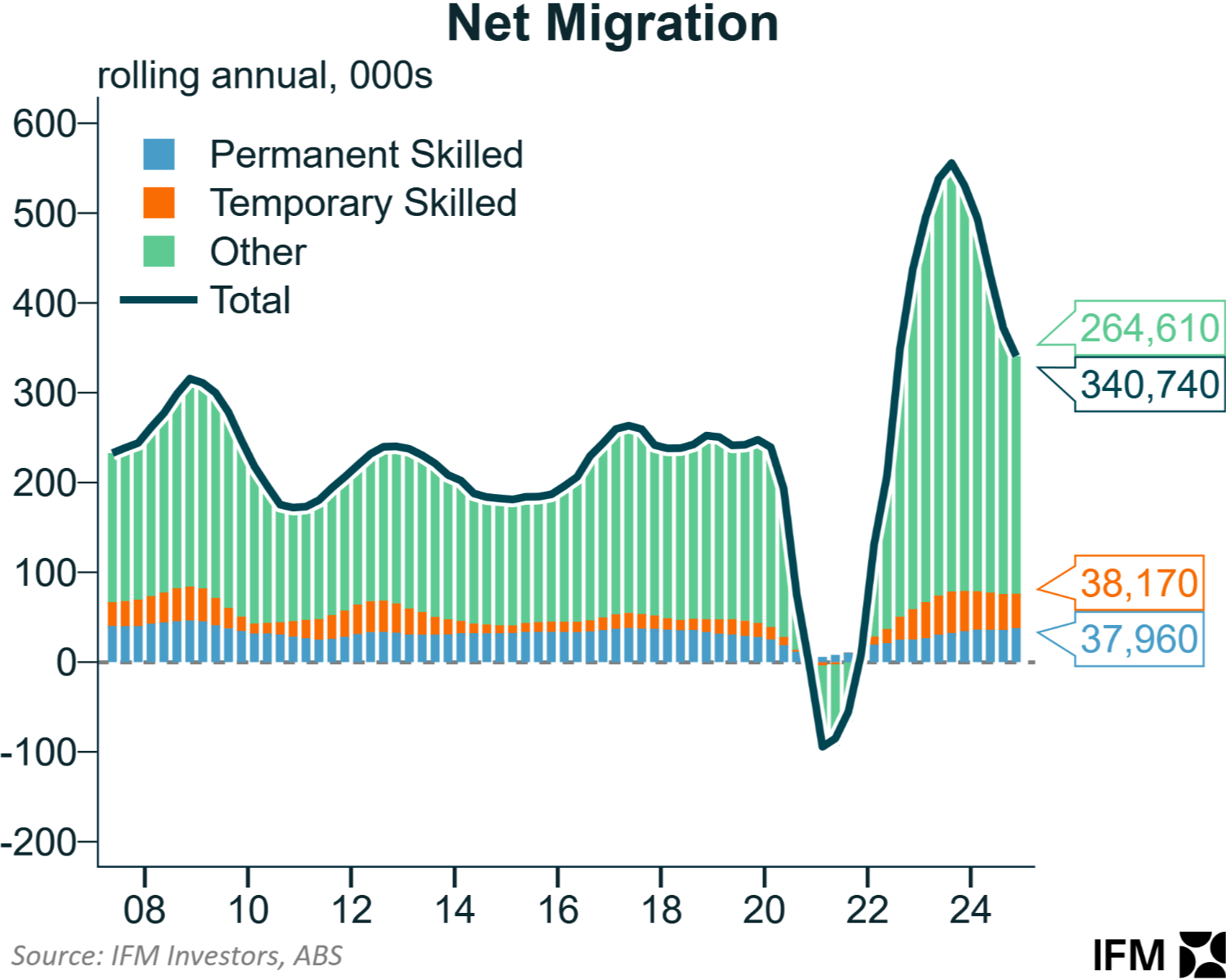

The relative oversupply of low-skilled workers is understandable, considering that the overwhelming majority of migrants arriving in Australia are unskilled.

As noted recently by pro-Big Australia shills Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen:

“Australia’s migration programme has failed to deliver what it promises”...

“It brings in relatively few genuinely skilled workers, while favouring family migration. It delivers few new skilled workers while being clogged with family visas”.

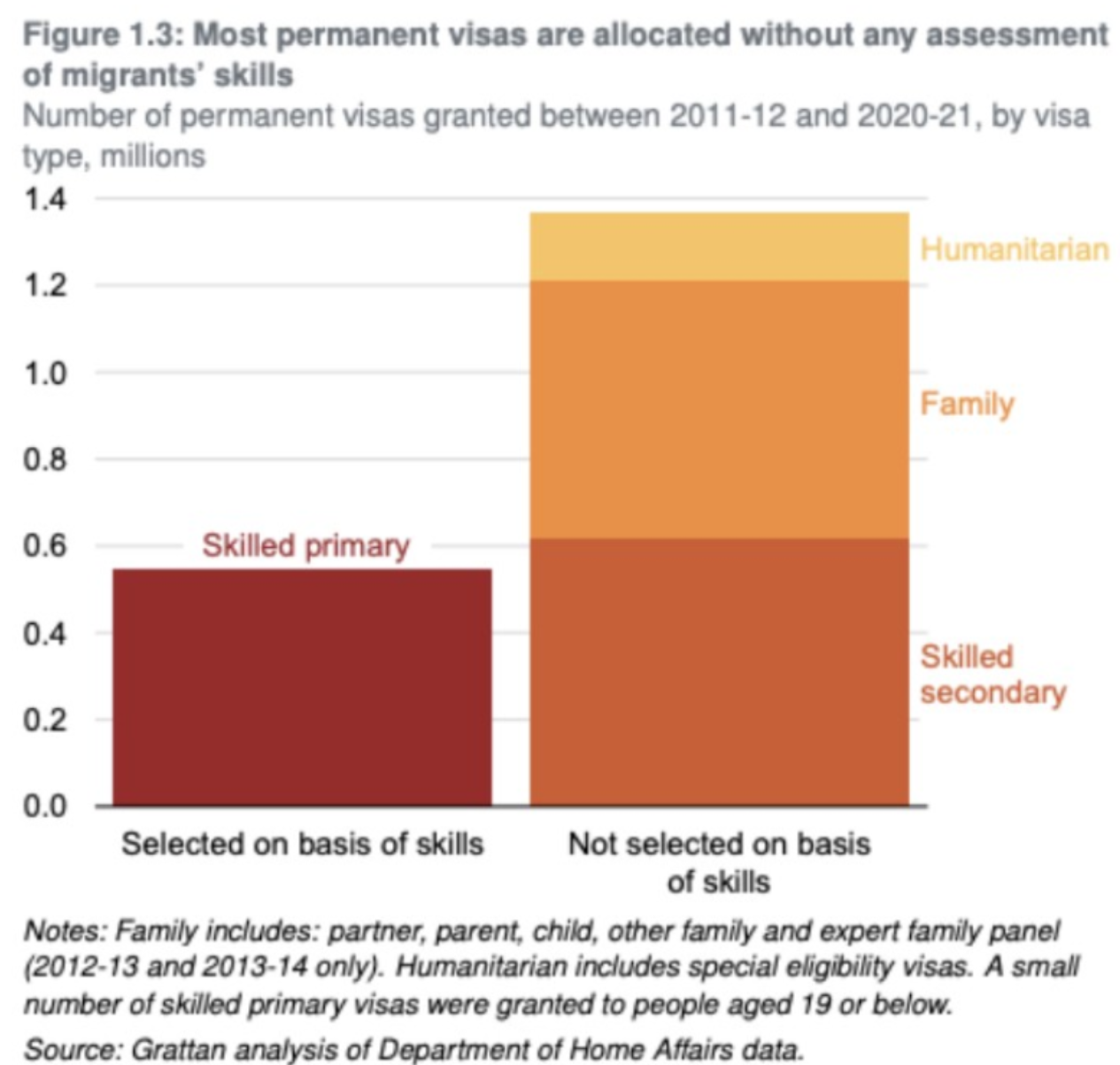

The following chart from the Grattan Institute shows similar outcomes:

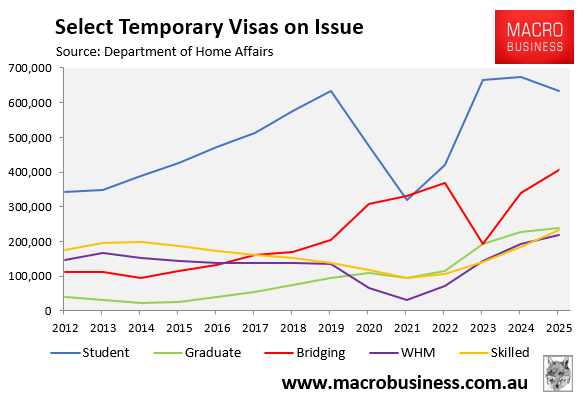

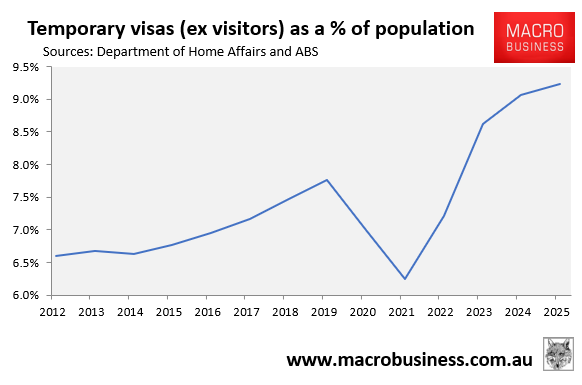

Australia’s temporary visa system, which has grown to nearly 2.6 million, is also overwhelmingly unskilled:

Even many migrants with skills are working in lower-skilled jobs.

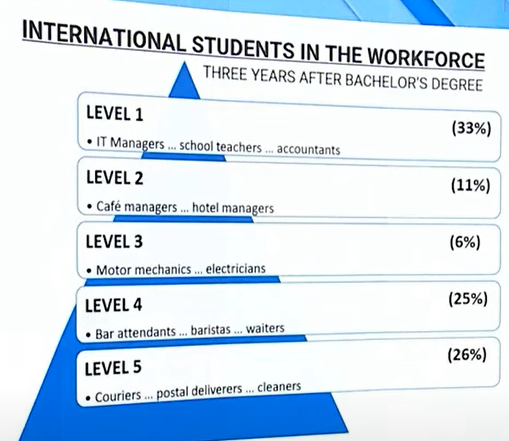

For example, the federal government’s 2023 Migration Review found that 51% of overseas-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review, 2023.

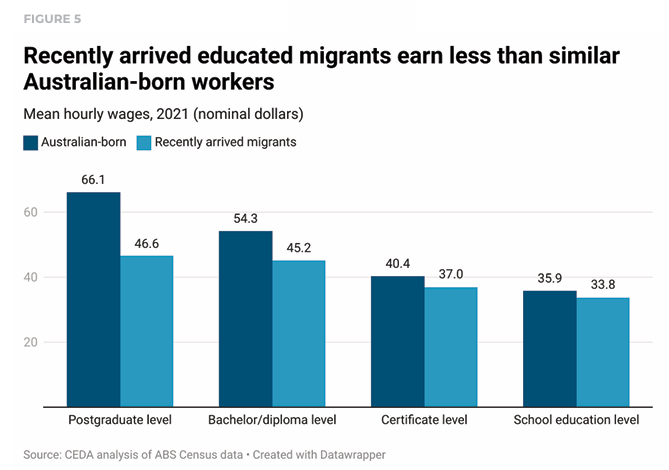

The Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) also reviewed the most recent census and discovered that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migrants are persistently underemployed and underpaid.

The Albanese government recently announced that it has raised the planning level for international students by 25,000 to 295,000 for 2026. Labor also watered down some English-language test requirements and lowered risk weightings for universities and students from South Asia.

As a result, Australia’s international student and temporary visa numbers—which are already the highest in the advanced world relative to our population—will inevitably increase.

The data is clear that Australia is importing giant volumes of people with the wrong skills, which is adding to housing and infrastructure strains and delivering lower productivity growth.

Australia needs to run a significantly smaller migration system focused on quality over quantity and importing genuine skills that the nation actually needs.