Indians exploit Australia’s visa system

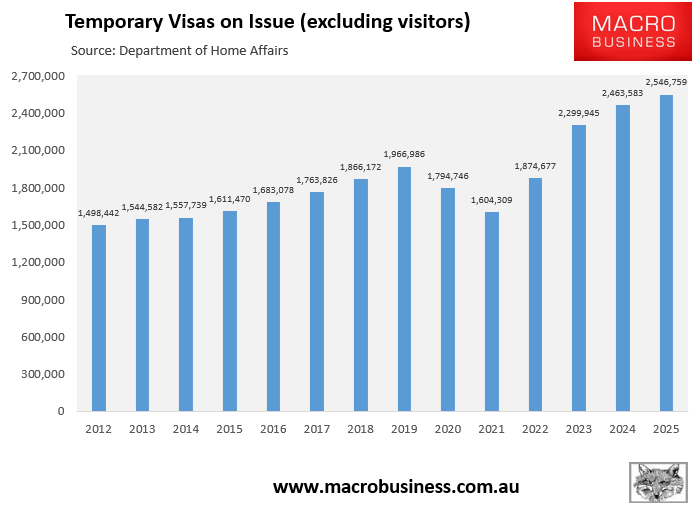

I reported earlier this week that the number of temporary visa holders in Australia (excluding visitors) hit a record high of 2,547,000 in the September quarter of 2025, up 83,200 on the prior year’s record:

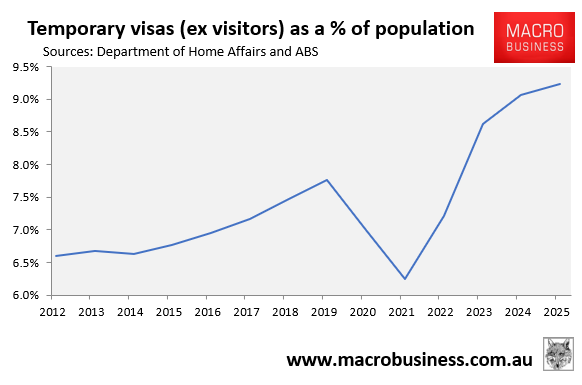

The share of Australia’s population on temporary visas has also ballooned to a record high of 9.2%, up from 7.2% in Q3 2022 just after Labor came to office and from the previous peak of 7.8% just prior to the pandemic.

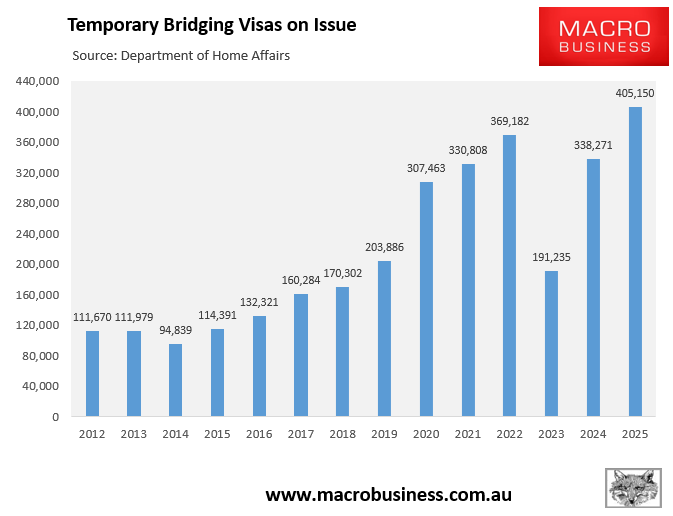

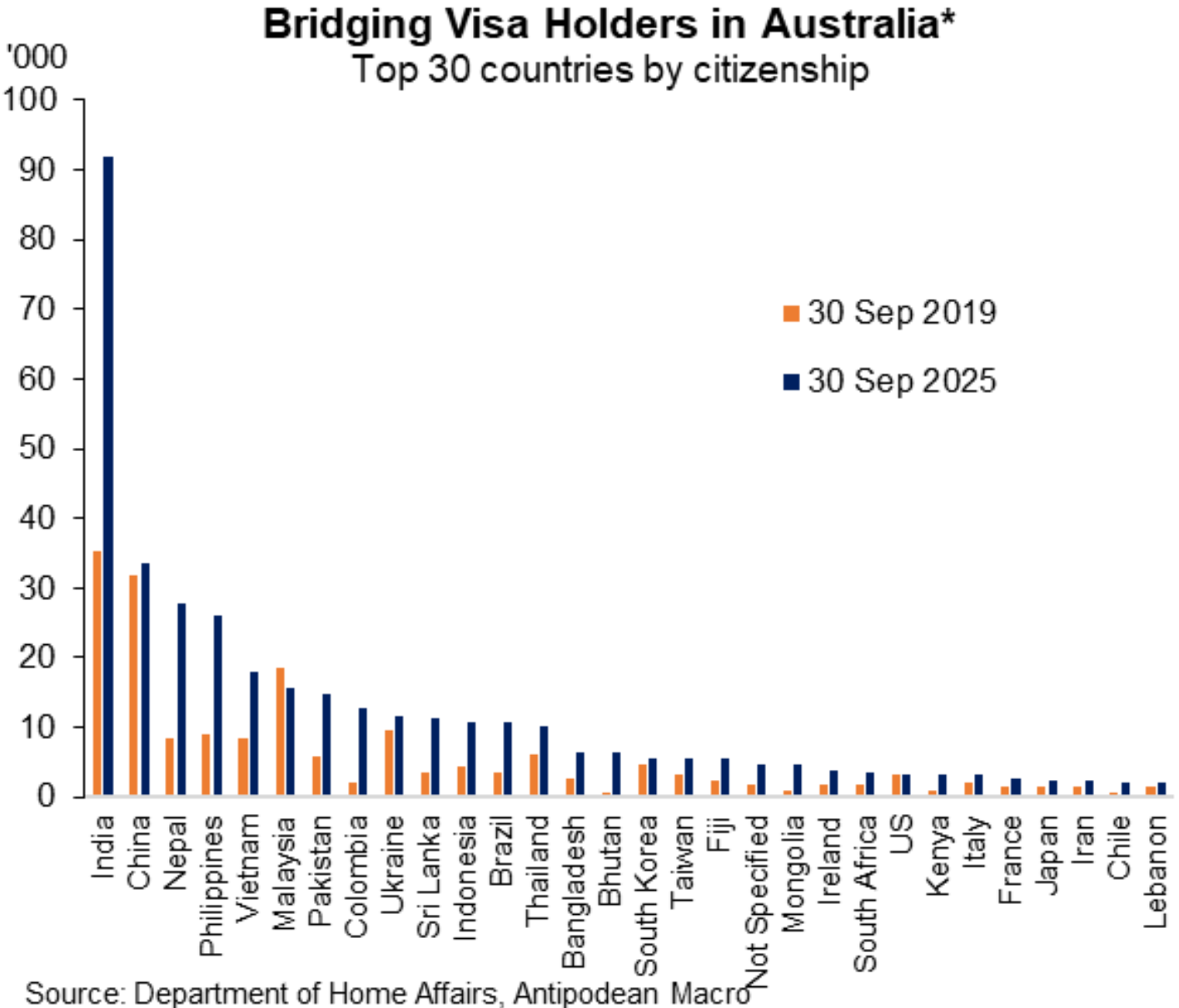

The single largest contributor to the surge in temporary migrants since the pandemic are bridging visas, which rose by 201,300 between Q3 2019 and Q3 2025:

Bridging visas are typically granted for two reasons:

- Bridging visas were handed out because the Department of Home Affairs was unable to process an onshore visa application before the substantive visa that the applicant was on expired.

- Bridging visas are handed to people whose substantive visas have expired while they make arrangements to depart.

Former senior immigration department bureaucrat Abul Rizvi claimed previously that bridging visas are “the most important barometer of the health of the visa system” and argued that the blowout in bridging visas is evidence of “administrative incompetence”.

The blowout in bridging visas appears to be driven in part by former students refusing to return home, given the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) is being clogged up with an “unprecedented surge” in appeals over student visa refusals, according to the Attorney-General’s Department.

“This massive caseload increase has been driven by an increase in student visa applications and the government’s crackdown on dodgy education providers while Labor also seeks to limit the number of international students coming into the country”, The Australian reported.

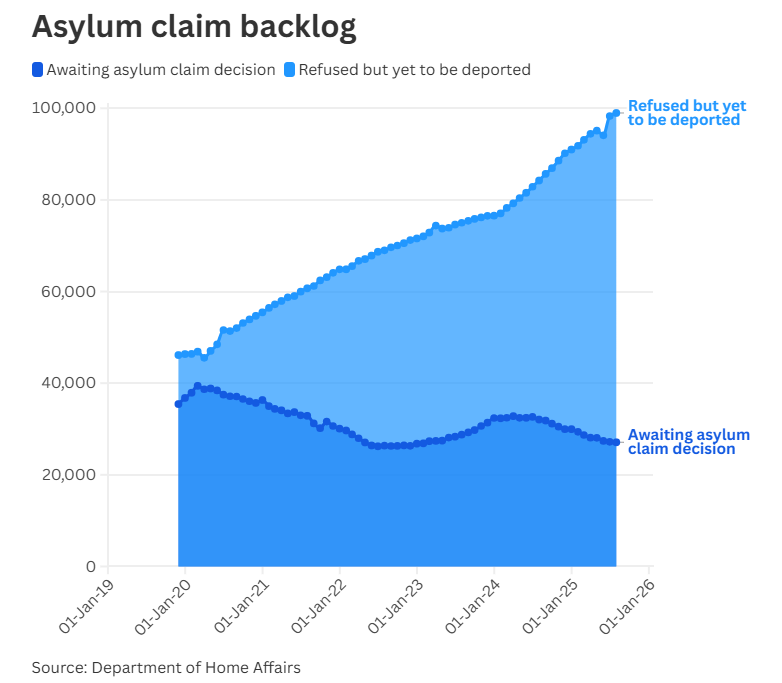

Frank Chung at News.com.au recently published an alarming report on the huge increase in migrants attempting to claim asylum.

“As of July 31, there were 98,979 people whose protection visa application had been denied but were yet to be deported while 27,100 were awaiting a decision, according to the Department of Home Affairs”, Chung reported.

Abul Rizvi told Chung that “there’s an increasing number of student visa holders applying for asylum”, and that “we want to at least stabilise it, otherwise you end up with a massive underclass and it impacts social cohesion, and eventually you get some strongman leader like Trump saying, ‘I’m going to fix it’”,

Rizvi added that there are likely to be around 50,000 migrants who have exhausted all their appeal avenues and remain in the country unlawfully.

Salvatore Babones, Associate Professor Sociology and Criminology at the University of Sydney and author of the 2021 book Australia’s Universities: Can They Reform?, warned that the student visa system is the “new scam”, noting the “emerging phenomenon” of people arriving in Australia on student visas “after which they can apply for a different visa”.

“They can easily get a bridging visa and then get a visa to study at a cooking school or a language school, and then you can stay in Australia almost indefinitely”, Babones said.

The surge in temporary migration and bridging visas is being driven by Indians.

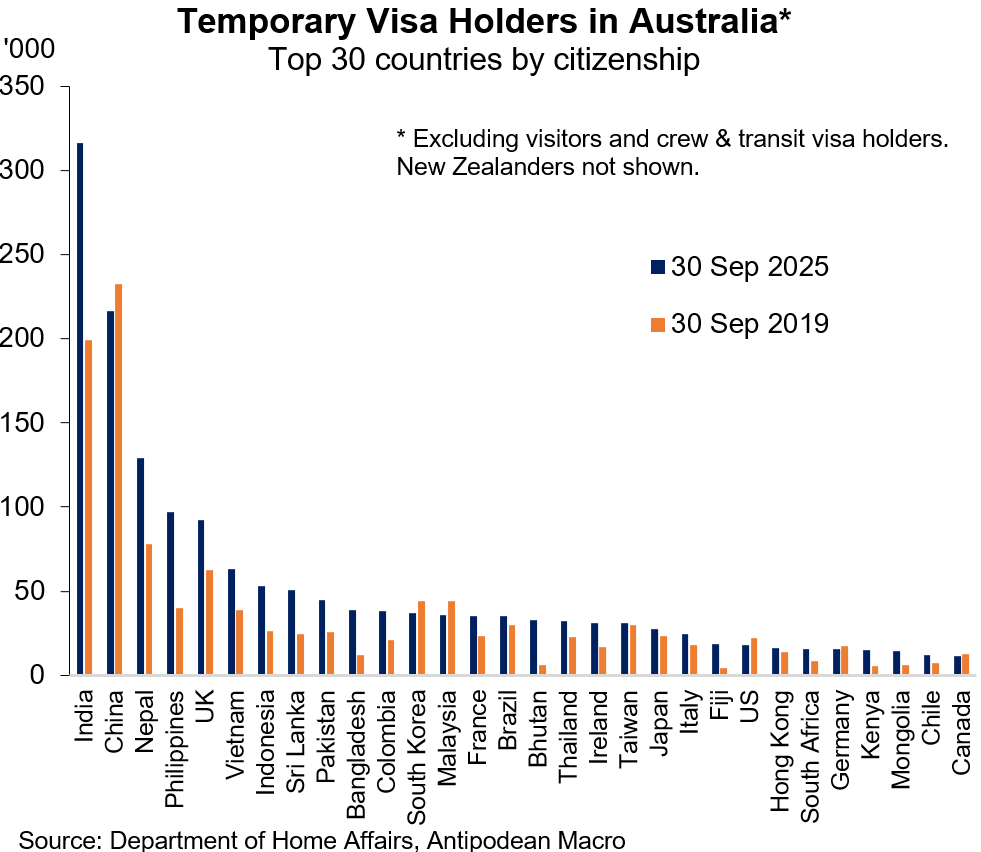

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, “Indian citizens in Australia held the most temporary visas by far, followed by Chinese citizens (who were #1 six years prior). (This analysis excludes NZ citizens.)”:

Indians have also contributed most to the growth in bridging visas, dwarfing every other source country:

The Australian government has signed three migration-related pacts that have made it easier for Indians to live and work in Australia, namely:

- The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), signed by the former Morrison Coalition government late in its last term, which made it easier for Indians to migrate to Australia.

- The Australia-India Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

- The Mechanism for Mutual Recognition of Qualifications, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

However, amid concerns of widespread rorting of the visa system by non-genuine students, the former Morrison Coalition government in 2019 deemed students from India, Nepal, and Pakistan “high-risk”, meaning they faced tighter scrutiny when applying for visas from the Department of Home Affairs.

As a result, several Australian educational institutions closed their doors to student applications from India. Even so, student numbers soared to record levels in the post-pandemic period.

Last month, Indian-Australian news outlet The Australia Today reported that “India’s assessment level for Australian student visas has shifted from Level 3 to Level 2, signalling easier application requirements for Indian students seeking to study Down Under”.

“Key changes include reduced upfront financial evidence and course-dependent English test requirements. Gold Coast–based registered migration agent Seema Chauhan told The Australia Today that this is a positive update for Indian international students seeking high-quality education opportunities in Australia”.

“With India now at Level 2 alongside countries like Bhutan, Vietnam, China, and Nepal, students and families can expect smoother admissions, fewer delays, and greater confidence in pursuing an Australian education”, The Australia Today reported.

Jobs & Skills Australia’s (JSA) latest report on the international education system noted that most international students come to Australia primarily to work and live, rather than for educational purposes.

“Nearly 70% of international higher education students reported that the possibility to migrate was a reason for choosing to study in Australia, rising to 77% of Indian and 79% of Nepali higher education students”, JSA reported.

Moreover, JSA noted that over 90% of Indian and nearly 96% of Nepali higher education students cited the ability to work while studying as one of the reasons they chose Australia. “80% of students from South and Central Asia (including India and Nepal) were working during study”, JSA said.

The reduced risk assessments for Indian students will likely increase the numbers seeking to live and work in Australia.

Thus, the Albanese government has opened the Indian student-migration pathway even wider.

Politically, this makes sense since Indians overwhelmingly vote for Labor, suggesting that the Albanese government is seeking to bolster Labor’s future voting base.