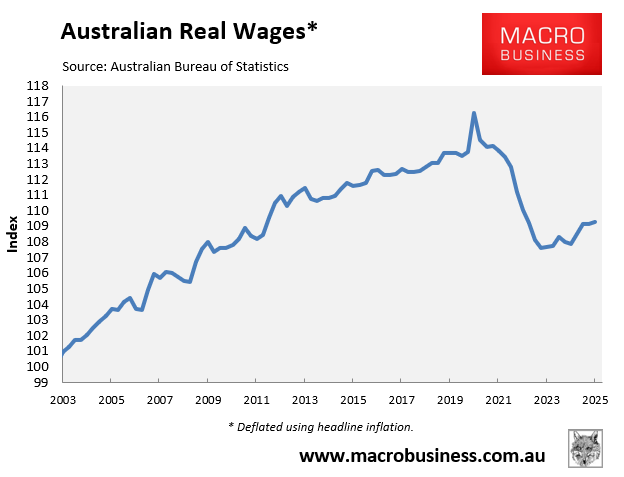

Australian real wages fell by a record 7.3% between mid-2020 and the September quarter of 2023. They have since recovered by a paltry 1.3%, leaving real wages 6.0% lower than their peak as of mid-2025.

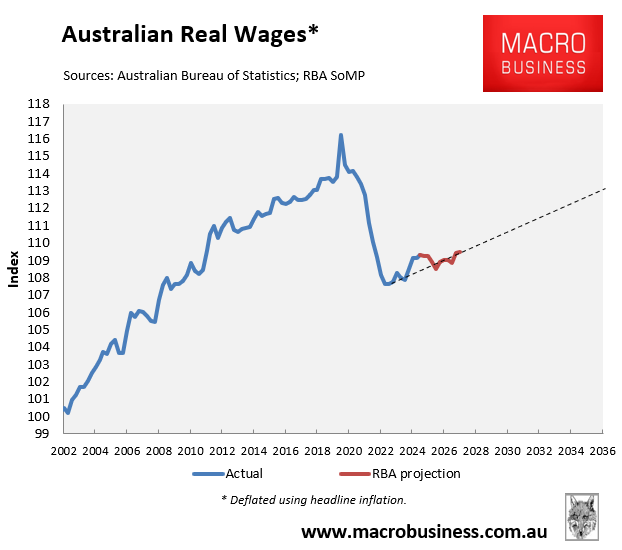

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) forecast in its November Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) that real wages would remain 5.8% below their peak, still tracking where they were at the end of 2011.

If the RBA’s forecasts are correct, this means that Australians would have experienced zero growth in their real wages in 16 years.

Extrapolating the RBA SoMP’s latest forecast also suggests that Australian real wages might not recover for another decade, until the mid-2030s.

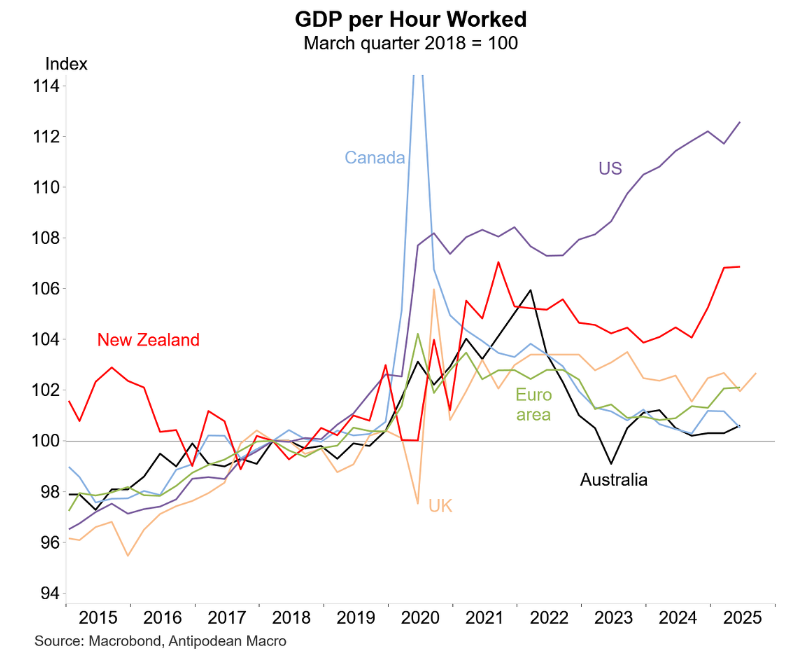

Unbelievably, Australia’s real wage growth should be even worse.

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, Australia’s labour productivity growth since the March quarter of 2018 ranks among the poorest in the developed world:

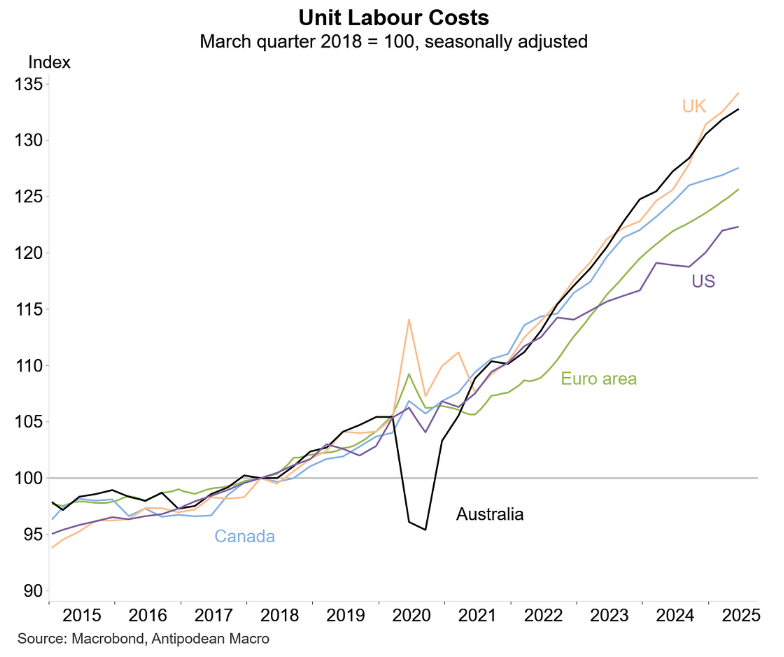

Unit labour costs (ULCs) measure the average cost of labour required to produce one unit of output. They are calculated as the ratio of total labour compensation (wages, salaries, and benefits) to labour productivity (output per hour worked).

ULCs show how much businesses pay workers to generate a single unit of goods or services.

For firms, if wages rise faster than productivity, ULCs increase, squeezing profit margins. Conversely, productivity gains can offset wage growth, keeping ULCs stable.

Justin Fabo shows below that the growth in unit labour costs in Australia ranks among the strongest in the developed world:

Therefore, Australian workers have gained wage growth at the expense of business profits, flattering real wages. Or put another way, had Australian ULCs risen in line with other advanced nations, real wages would be even lower than they currently are.

Gerard Minack explained these dynamics in his latest post published on MacroBusiness:

Without productivity growth—or a terms of trade windfall—income is a zero sum game: real wages, for example, can only grow at the expense of profits…

The nominal wage growth that is compatible with the RBA’s 2-3% inflation target falls as productivity growth slows. With zero productivity growth, nominal wage growth would need to be around 2½-3% to be consistent with 2½% inflation (allowing for the fact the price of goods–many imported—tends to fall in real terms).

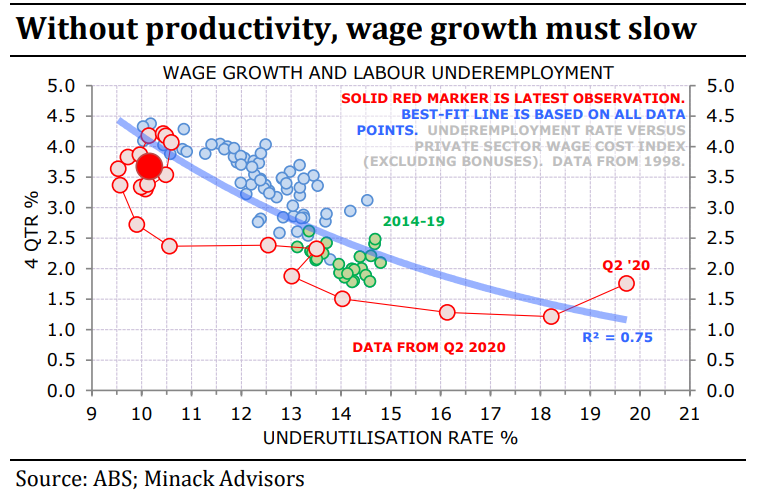

The RBA may keep the current modestly restrictive policy on hold until the labour market loosens enough to reduce wage growth to 3% or below…

Given that Australia’s terms of trade are likely to fall amid declining commodity prices (e.g., iron ore prices), for real wages to rebound, labour productivity must rise.