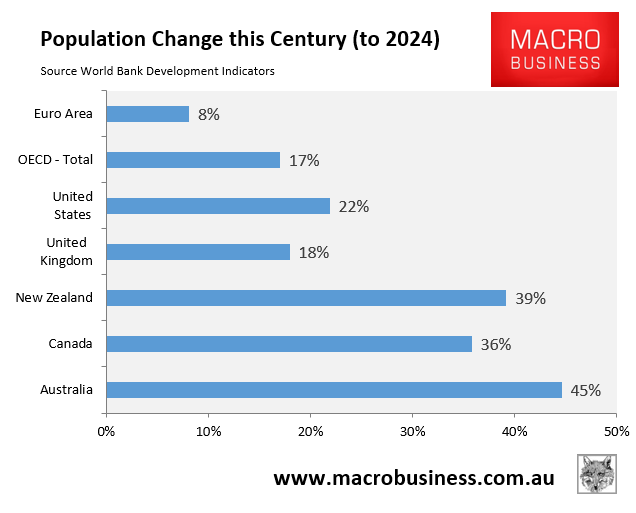

Alan Kohler is one of the few ABC journalists willing to openly and honestly discuss Australia’s immigration system, which is the fundamental driver of the nation’s world-beating population growth.

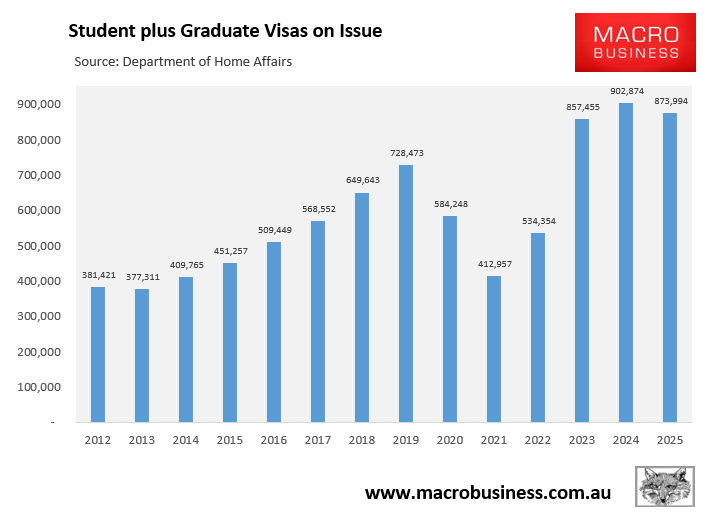

The following video presentation by Kohler explained how the surge in international students in Australia is one of the key drivers of the nation’s high immigration-driven population growth, and ergo the nation’s chronic housing shortages.

“Education has a lot to do with housing affordability and the lack of it”, Kohler argues.

“Of the four and a half million migrants who came to Australia over the past 10 years, 1.6 million were students. It’s by far the largest component of our immigration program”.

“Now, in its planning for the budget, Treasury assumed that 16% of students got permanent residency. But it’s actually more than 40%”.

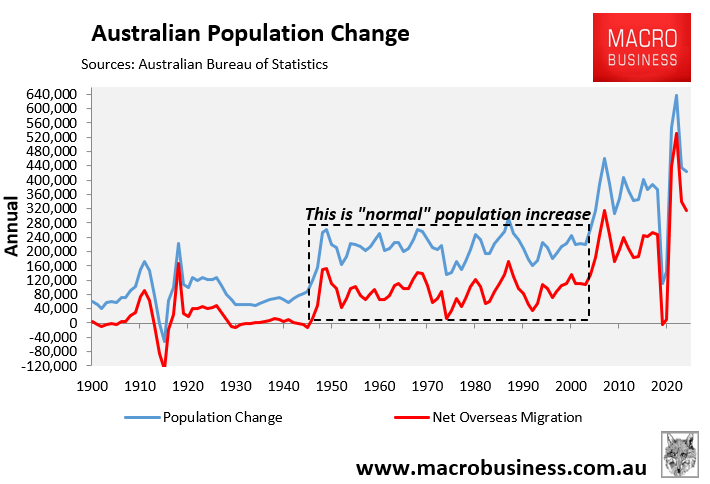

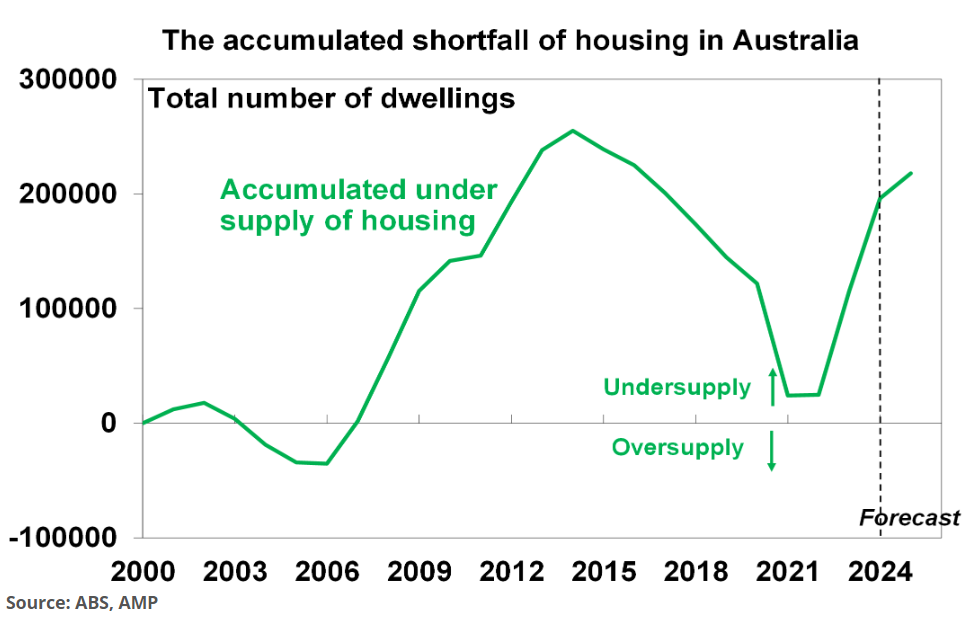

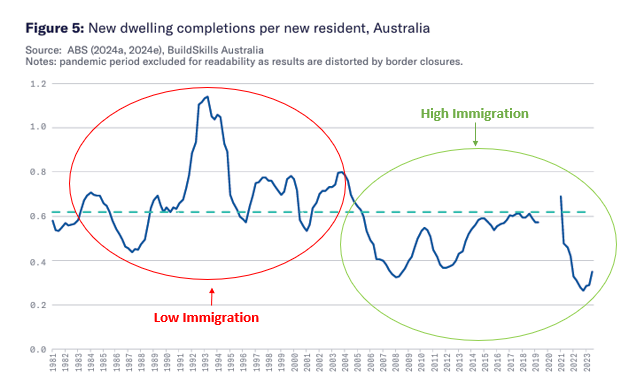

“That increase in student numbers contributed to a doubling of immigration in the mid-2000s and that in turn contributed to an under supply of housing for 15 years”, Kohler argues.

Source: AMP (Shane Oliver)

Kohler also correctly notes that Australia’s migration system does not import enough migrants with trade skills. Contrary to the post-war migration boom, which saw huge volumes of construction workers from Europe that helped to build Australia, few of today’s migrants from Asia work in the construction trades.

“No trades are coming from India and China now to build the houses they need”, Kohler noted. “They’re mostly commerce students or cooks”.

To add further insult to injury, young Australians have been encouraged to study at university instead of pursuing a trade.

“The result is the construction sector employment has been static for 20 years, even as demand for housing has increased”, Kohler argues.

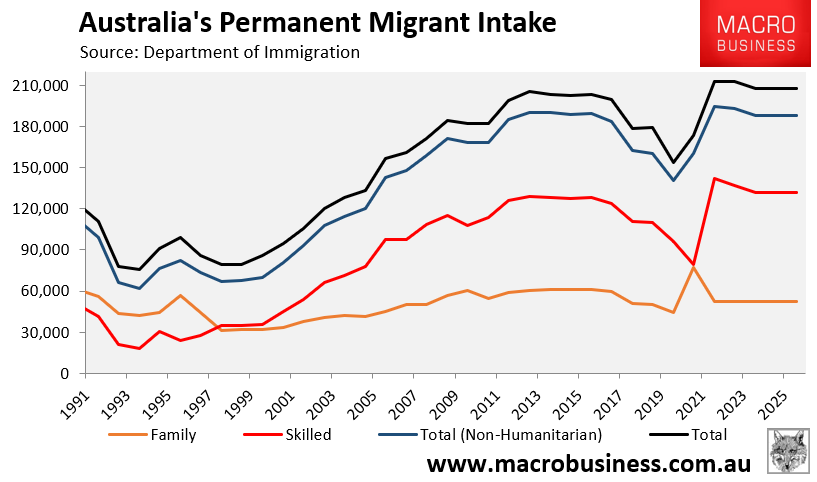

The only point that I will add is that the federal government has also dramatically increased the permanent migrant intake.

At the turn of the century, Australia’s permanent plus humanitarian migrant intake was only 86,000. As of 2025, the official intake was 205,000:

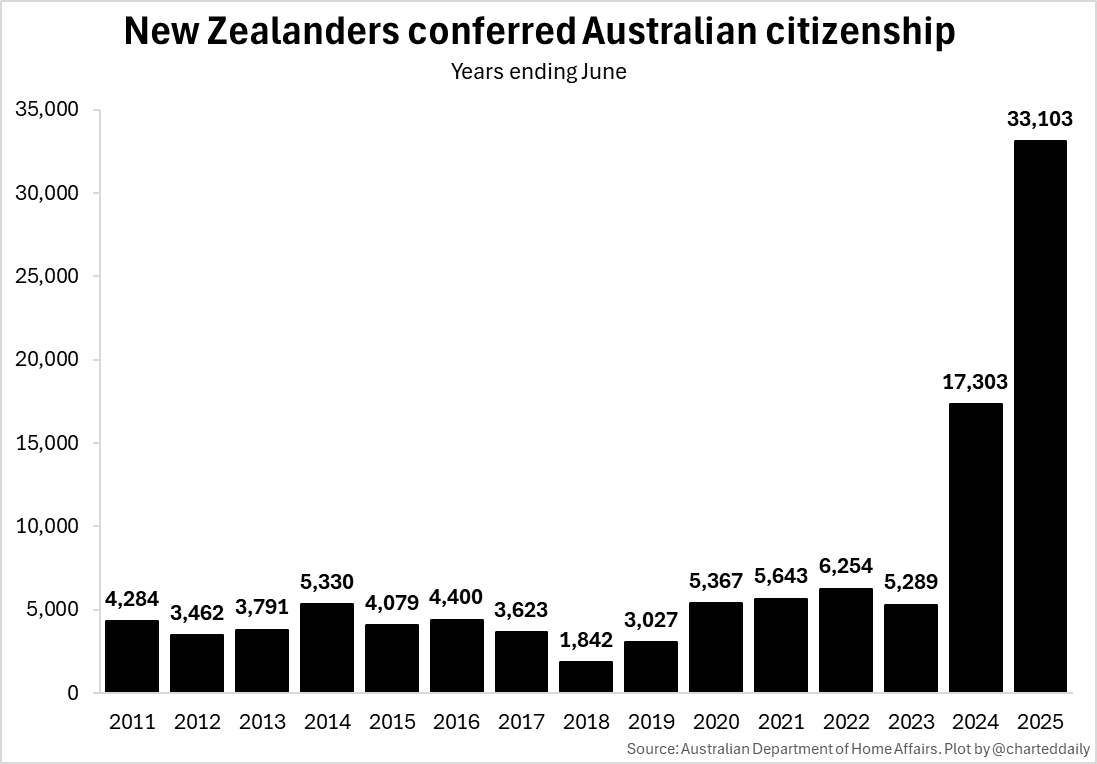

However, following changes implemented by the Albanese government from 1 July 2023, New Zealand citizens who have lived in Australia for four years or more on a Special Category Visa (SCV) are permitted to apply directly for Australian citizenship by conferral, without first becoming a permanent resident.

Other nationalities now occupy the places formerly taken by Kiwis, effectively increasing the size of Australia’s permanent migrant program by around 30,000 places.

The Albanese government also placed 3,000 Pacific Engagement Visas, which are permanent residence visas, outside of the official permanent migration program cap of 185,000.

The upshot of these policy changes by the Albanese government is that the annual effective permanent migration plus humanitarian program is now around 235,000 places, not the stated 205,000. It is also around 170% higher than the level at the turn of the century.

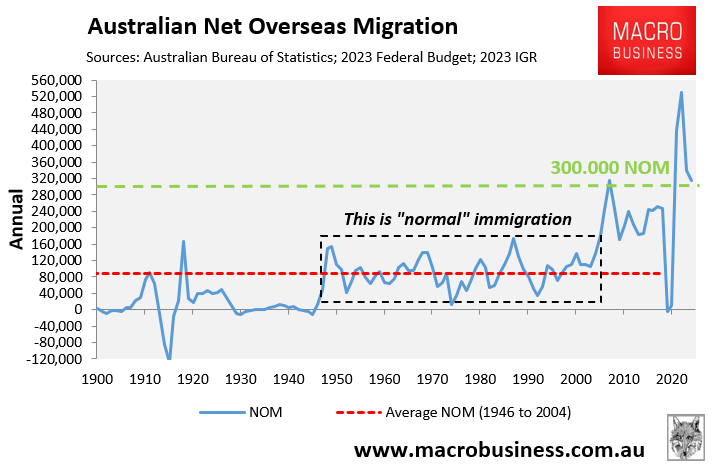

The bottom line is that multiple levers have been pulled by the federal government to expand immigration into Australia, which has driven the nation’s structural housing shortage.

With Abul Rizvi now forecasting that Australia’s net overseas migration will average around 300,000 annually going forward under current policy settings, which is 15% higher than Treasury’s own lofty forecasts, it means that the housing shortage can only worsen.

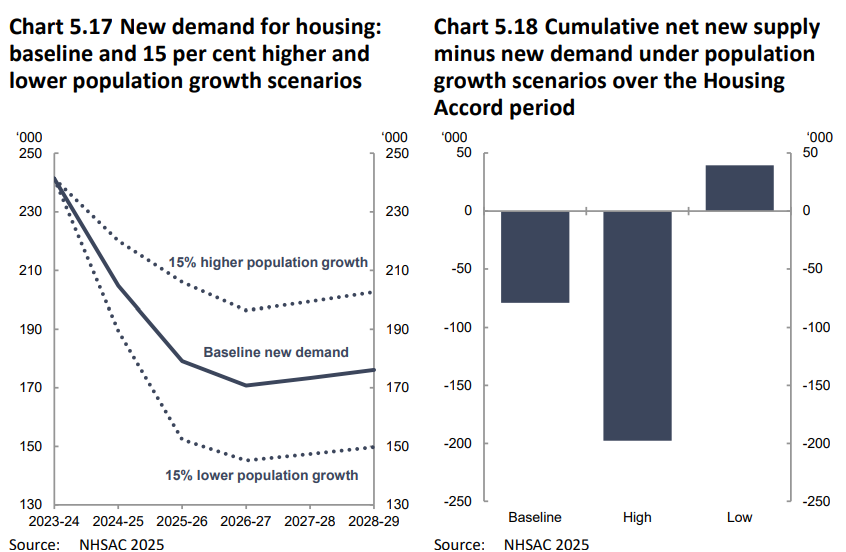

Indeed, the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council’s (NHSAC) latest State of the Housing System report, released in May, forecasts that if Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, as suggested it will by Abul Rizvi, then Australia’s housing shortage will increase by around 200,000 over five years.

This 200,000 forecast increase in the housing shortage is on top of the current cumulative shortage of at least 200,000 homes, calculated by AMP chief economist Shane Oliver, shown above.

Australian renters will suffer the most as population demand forever outstrips supply.