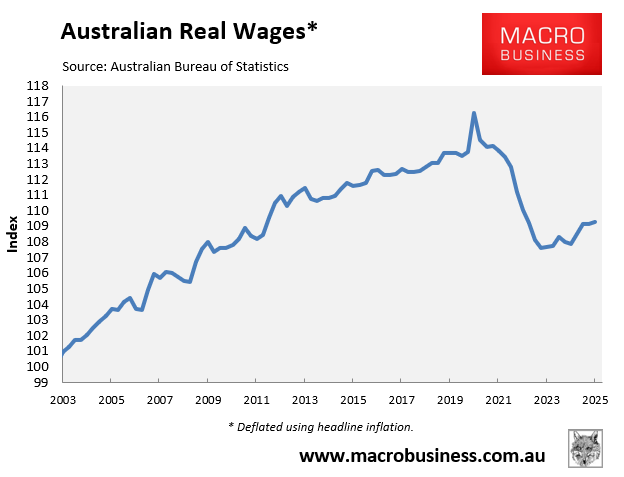

Australians have endured the biggest decline in real wages in history.

As of the June quarter of 2025, Australian real wages were still tracking 6.0% below their June 2020 level, at roughly the same level as December 2011.

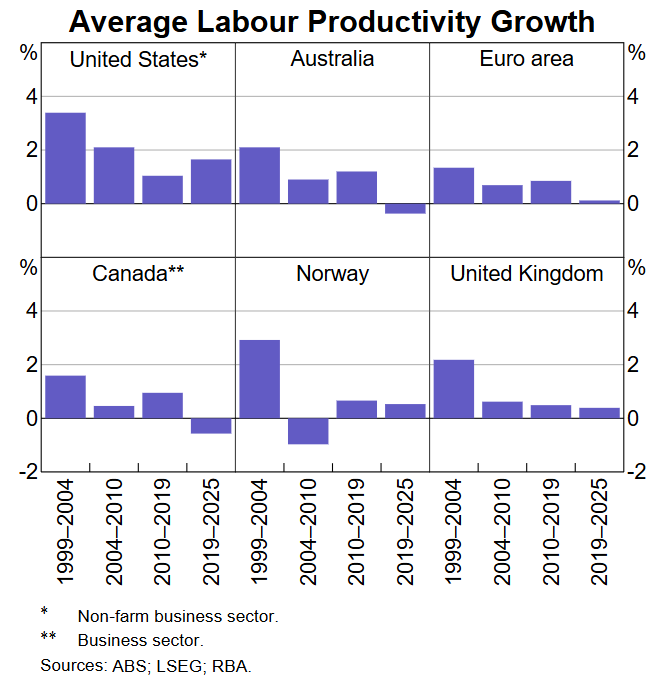

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) Assistant governor and chief economist Sarah Hunter warned that Australia’s sagging recent labour productivity growth, which is among the worst in the advanced world, would crimp wage growth in the future.

In a speech at the Citi Investment Conference in Sydney, Hunter stated that the maximum wage growth the economy could sustain was 3.2% per year on average, down from 3.5% based on the RBA’s previous productivity assumptions.

“The productivity downgrade lowers our assessment of this rate from around 3.5% to around 3.2% when wages are measured using Average Earnings in the National Accounts (AENA)”, Hunter said.

“Unfortunately, the ‘productivity growth plus 2.5% rule’ does not work as neatly for the Wage Price Index (WPI) due to the way it’s constructed. The equivalent calculation for the WPI would suggest a rate slightly below 3%, but this should be interpreted with a bit more caution”.

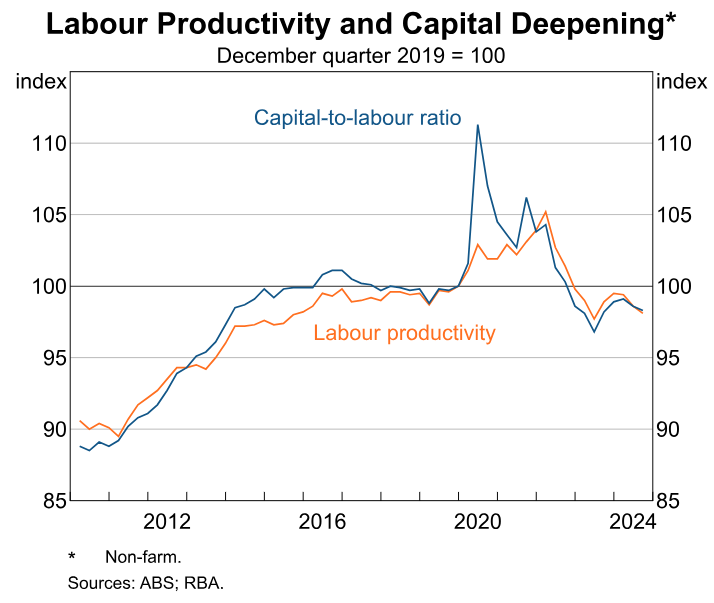

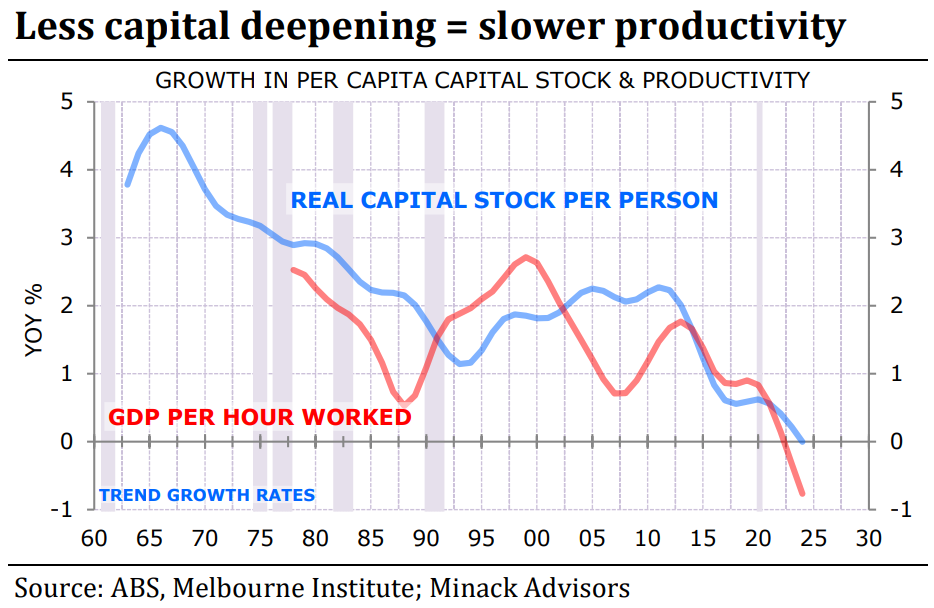

Hunter identified Australia’s decline in capital deepening (‘capital shallowing’)—i.e., the decline in the capital to labour ratio—as a reason for Australia’s poor productivity growth.

“Capital deepening, which measures the rate of increase in the amount of capital available to each worker, is happening more slowly”, Hunter said.

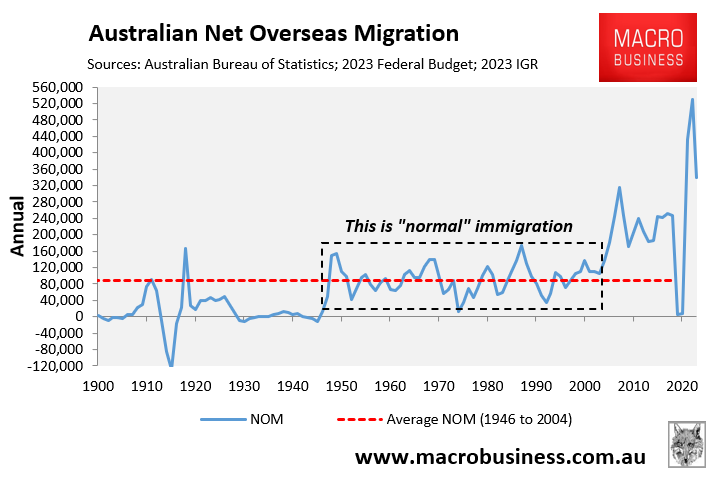

However, as usual, she failed to mention that Australia’s excessive and largely low-skilled migration system is contributing to the problem.

Essentially, Australia is facing the worst of two worlds.

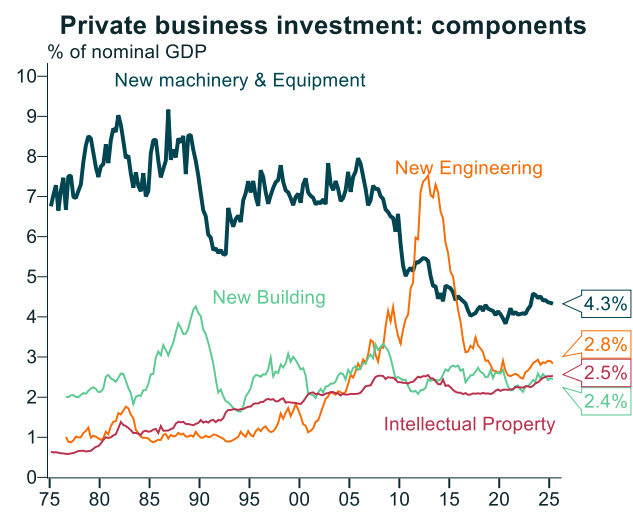

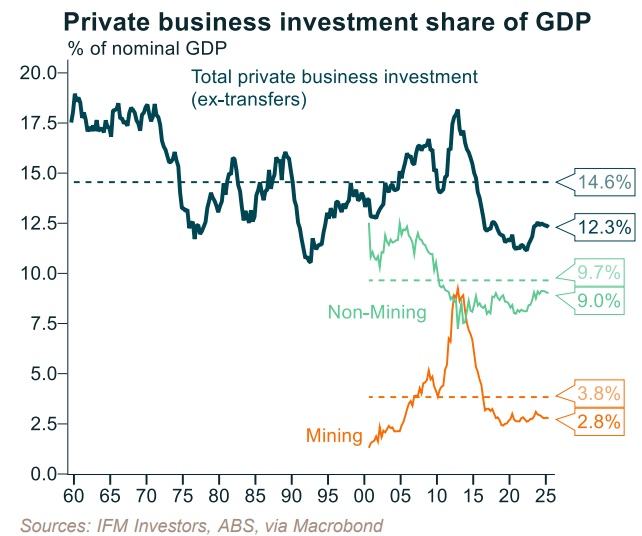

First, the volume of business investment, particularly machinery and equipment, is tracking near recessionary levels at roughly half the historical norm as a percentage of GDP. This low business investment has reduced the numerator of the capital-to-labour ratio.

At the same time, the denominator of the capital-to-labour ratio has grown aggressively via the federal government’s mass migration policy, which has rapidly expanded the labour force.

The end result is that low rates of business investment have been diluted by high rates of labour supply growth, lowering labour productivity and workers have fewer tools, machinery, and technology to work with.

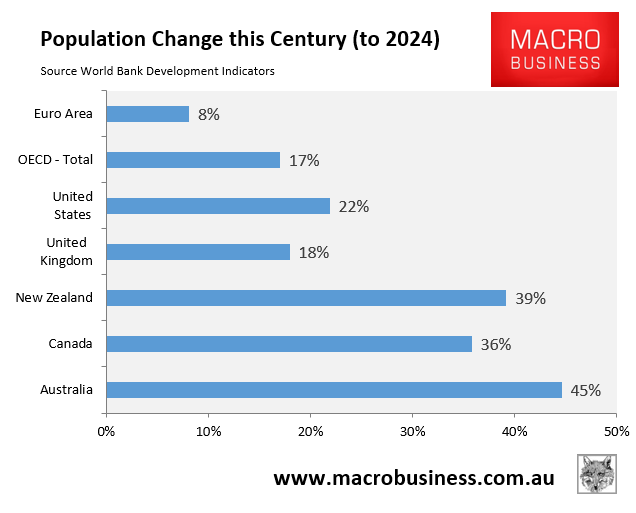

The reality is that Australia’s population has grown significantly faster than other advanced nations this century and has easily outpaced business, infrastructure, and housing investment, contributing to the nation’s decline in ‘capital deepening’.

Australia has failed to equip the millions of additional migrant workers with the necessary tools, machinery, and technology, as well as provide enough dwellings and infrastructure for the millions of additional families.

As a result, everyone’s standard of living has decreased.

This decline in ‘capital deepening’ has negatively impacted Australia’s productivity by reducing the quantity of capital investment per person.

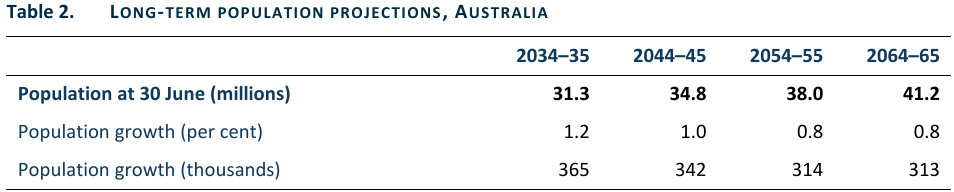

It is hard to see how Australia can realistically lift the capital-to-labour ratio, i.e., experience ‘capital deepening’, and lift productivity growth when it has committed to increasing the nation’s population by 13.5 million over the next 40 years.

Source: Centre for population

Adding the equivalent of another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to Australia’s current population in just 40 years will require an unprecedented amount of investment in business, infrastructure, and housing to simply maintain the capital stock per person.

Achieving such extraordinary levels of investment is an impossible task, meaning that the Australian economy will inevitably suffer ‘capital shallowing’ and slower productivity growth.

The question is, why won’t the RBA acknowledge that Australia’s high rate of mostly low-skilled immigration—the denominator of the capital-to-labour ratio—is a critical factor behind Australia’s capital shallowing? Why has it censored itself from mentioning immigration in the productivity debate?