International students refuse to return home

I reported this week on Jobs & Skills Australia’s (JSA) latest study on the international education sector, which admitted that the primary motivation for international students to choose Australia is to obtain work rights and permanent residency.

Nearly 70% of international higher education students reported migration as a key factor in their decision to study in Australia.

“For many students, migration aspirations are a primary goal”, JSA says. “The purpose underlying the choices of many students was to seek permanent residence in Australia”.

“Graduates’ persistence means they have become an important feeder group to Australia’s permanent migration program. Many international students have moved from one temporary visa to another, extending their time in Australia along the way. Some have pursued a pathway that tracks a course to permanent residency”.

“Longer-term analysis shows that more graduates are staying than previously estimated. As noted above, many international students remain in Australia as graduates for significant periods following their study and seek permanent residency”, JSA wrote.

JSA cited an engineering employer who said a foreign graduate told him “a lot of his mates just come here to earn the money, drive the Uber’’.

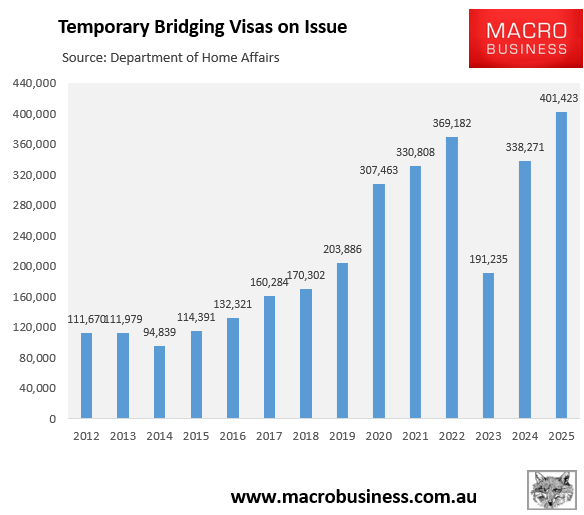

The Department of Home Affairs has released data showing that the number of bridging visas on issue in August exceeded 400,000 for the first time in Australia’s history.

The blowout in bridging visas appears to be driven in part by former students refusing to return home, given the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) is being clogged up with an “unprecedented surge” in appeals over student visa refusals, according to the Attorney-General’s Department.

“This massive caseload increase has been driven by an increase in student visa applications and the government’s crackdown on dodgy education providers while Labor also seeks to limit the number of international students coming into the country”, The Australian reported.

“Figures published by the department show that in 2018-19 – before the pandemic – 5499 lodgments challenging student visa refusals made up 9.1% of total lodgments”.

“But by 2024-25, this had blown out to 32,187, or 38.6% of total lodgments”.

There are more than 100,000 prospective or former students on temporary bridging visas.

Australian policymakers should be aiming to recruit a smaller pool of high-quality (authentic) students instead of continually lowering standards to attract more international students of doubtful quality that refuse to leave.

Quality could be improved via the following types of reforms:

- Significantly raising English-language requirements and requiring prospective students to sit entrance exams before being admitted to study in Australia.

- Significantly raising financial requirements, including the obligation to deposit funds into an escrow account before landing in Australia.

- Limiting the number of hours that overseas students can work and removing the direct link between study, work, and permanent residency.

- Allowing only exceptional graduates in areas of genuine shortage to obtain graduate visas.

- Allowing only postgraduate international students to bring family members.

- Because Australian universities are non-profit corporations that do not pay taxes, placing a levy on international students to ensure that Australians benefit financially from the trade.

Universities should also be required to provide on-campus accommodation for international students in proportion to the number of enrolled students to relieve pressure on the rental market.

Unfortunately, the Albanese government has chosen the opposite path by lifting the international student planning level by 25,000 for 2026 and lowering some English-language tests.