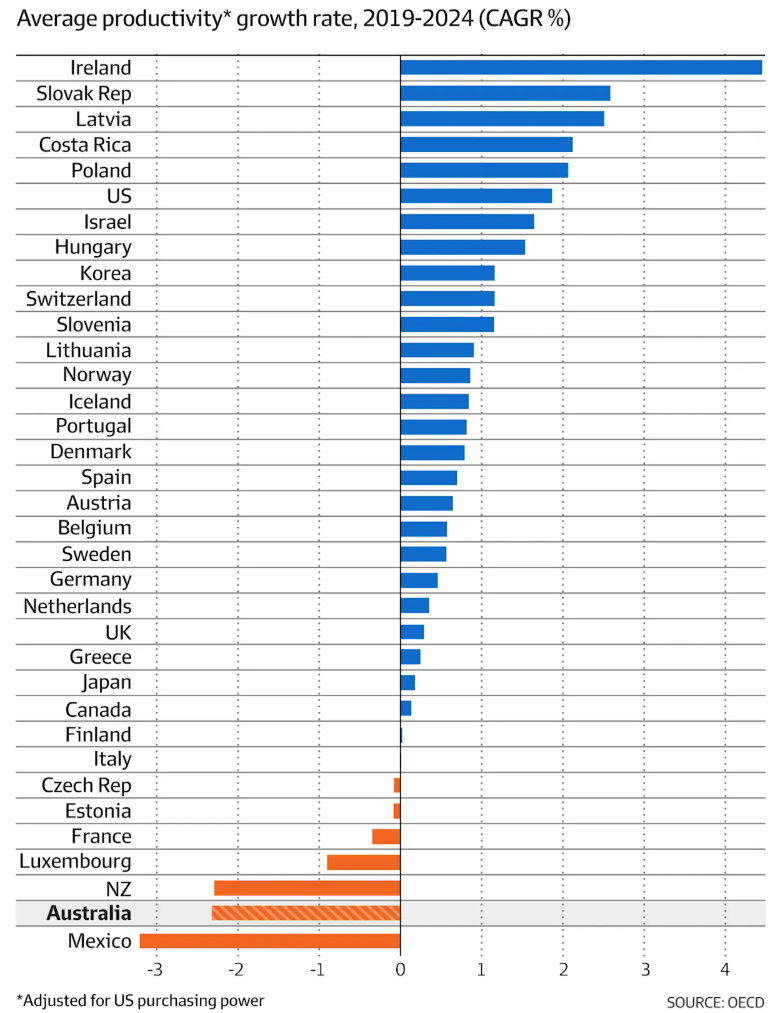

Analysis from the OECD, published in The AFR, shows that Australia ranks second-last among wealthy nations in terms of productivity growth since the COVID-19 pandemic.

EY’s chief economist, Cherelle Murphy, says the decline is partly attributable to “capital shallowing”—the fact that local companies are not investing enough capital in new equipment to match the growth in their workforce.

“We’ve had strong labour market performance, but at the same time, we have not had particularly strong business investment or innovation”, she said.

“You’re not going to get strong productivity growth because you’re essentially asking workers to work with capital equipment that’s not keeping up with the number of workers”.

Murphy added that corporate Australia’s expenditure on research and development is also below that of other countries.

It is good to see Australia’s economic fraternity catch up with MB’s view of Australia’s productivity decline.

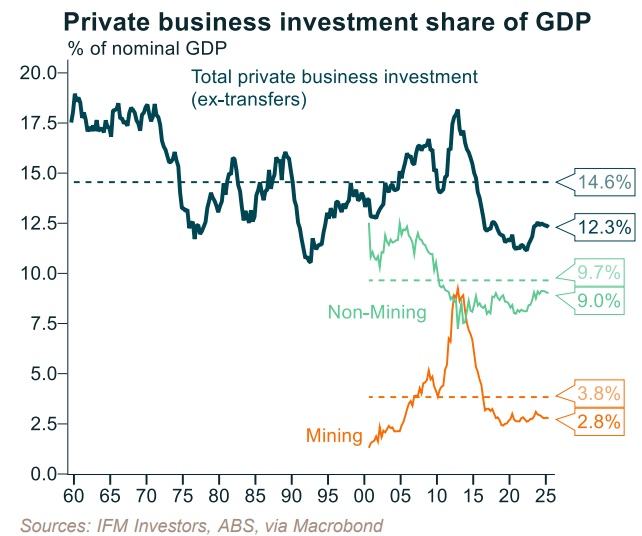

As Alex Joiner from IFM Investors illustrates below, private business investment as a share of GDP remains near recessionary levels.

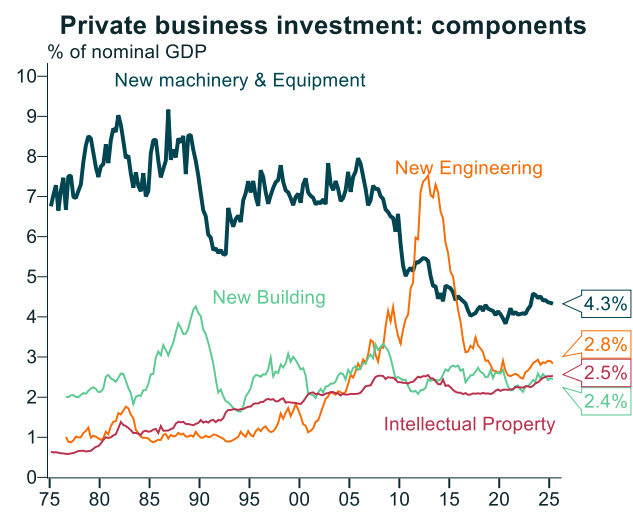

New machinery and equipment—vital to increasing worker productivity—are tracking at historically low levels as a share of GDP. At 4.3% of GDP, it is tracking at around half what it was two decades ago:

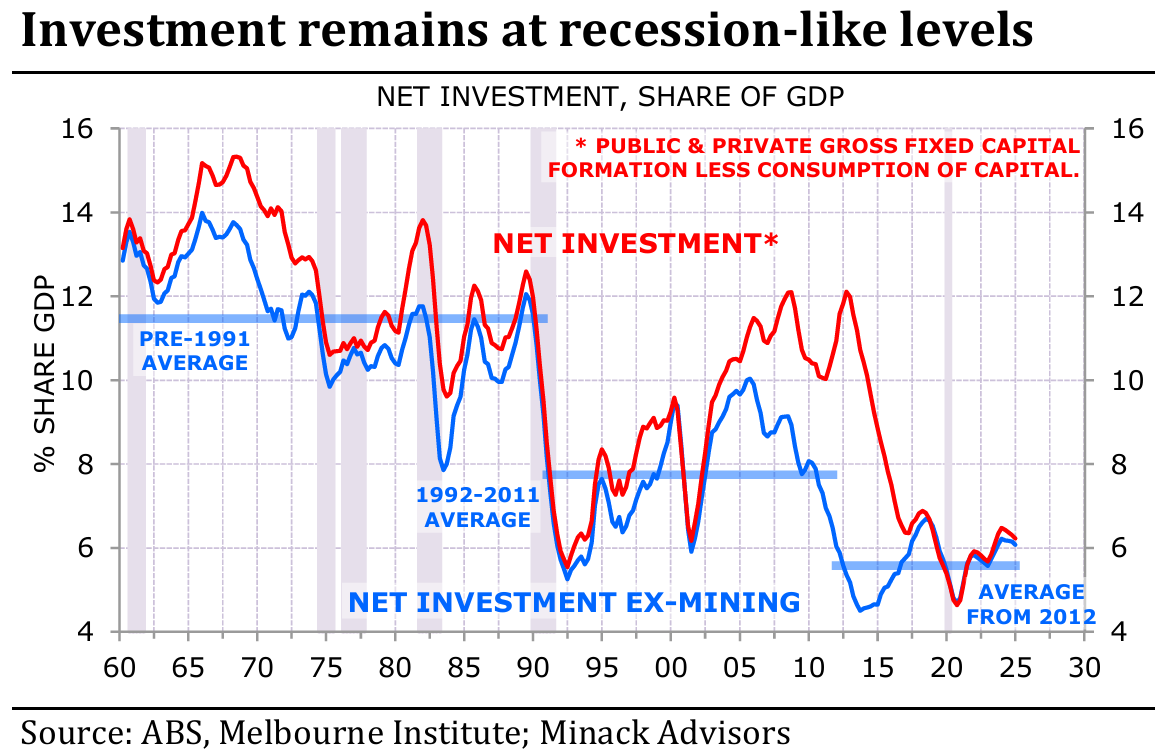

Leading independent economist Gerard Minack likewise illustrated that net investment in Australia is tracking at recessionary levels:

Therefore, it is true that investment—the numerator of the capital-to-labour ratio—has been soft, tracking near recessionary levels.

Meanwhile, the denominator of the capital-to-labour ratio has grown rapidly via high volumes of low-skilled immigration.

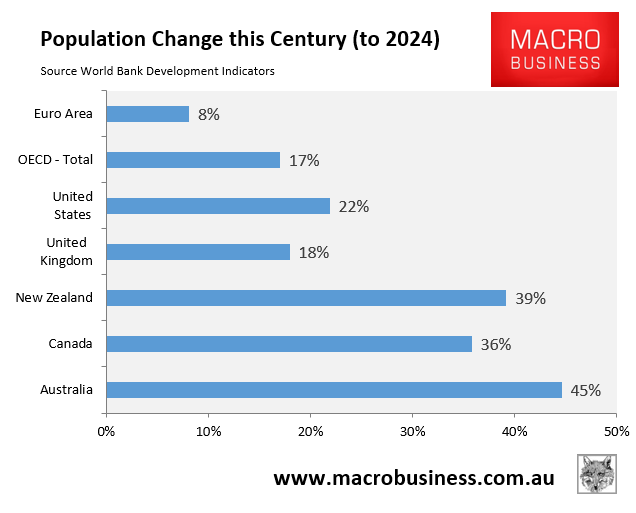

Australia’s population has grown significantly faster than that of other advanced nations this century and has easily outpaced investment in business, infrastructure, and housing. This has contributed equally to the nation’s ‘capital shallowing’.

Australia has failed to equip the millions of additional migrant workers with the necessary tools, machinery, and technology. It hasn’t provided enough dwellings and infrastructure for the millions of additional families.

As a result, everyone’s standard of living has decreased.

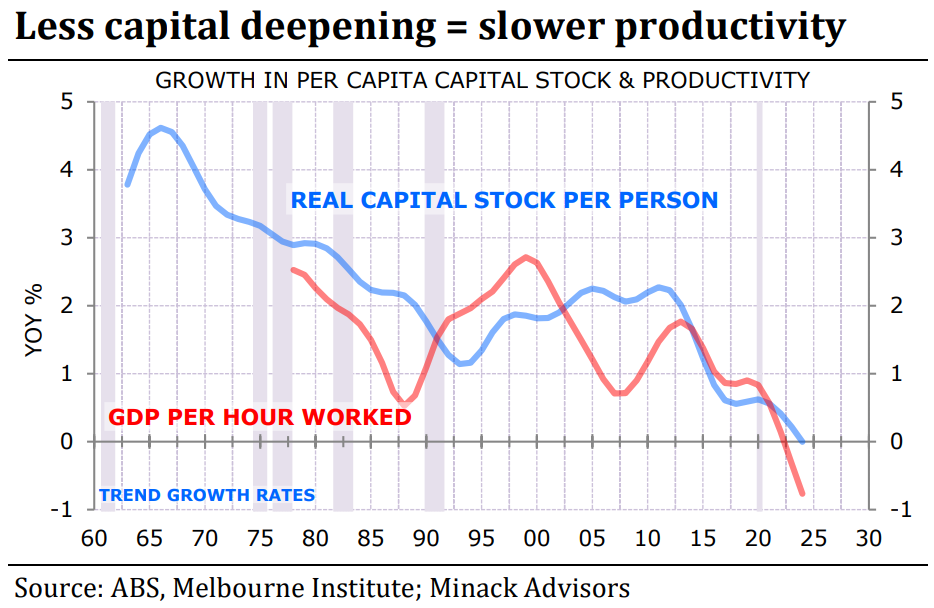

This ‘capital shallowing’ has negatively impacted Australia’s productivity by reducing the quantity of capital invested per person.

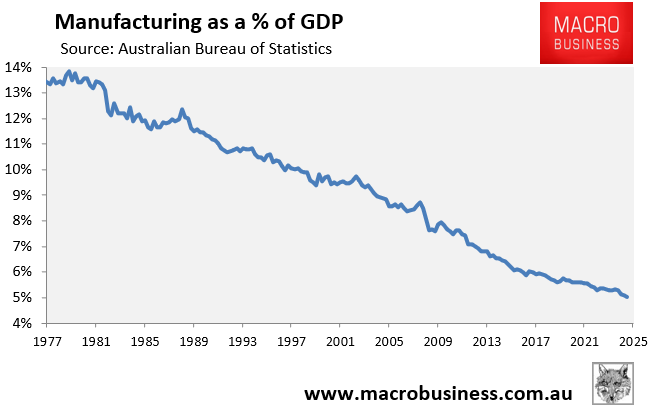

It is hard to see how Australia can realistically increase the capital-to-labour ratio, i.e., experience ‘capital deepening’, and lift productivity growth when its manufacturing sector is in terminal decline amid soaring energy costs.

With energy costs poised to soar amid net-zero policies and gas policy failures, Australia will inevitably continue to deindustrialise and send what’s left of its manufacturing sector to lower-energy-cost nations. In turn, companies will wind down capital investment in Australia.

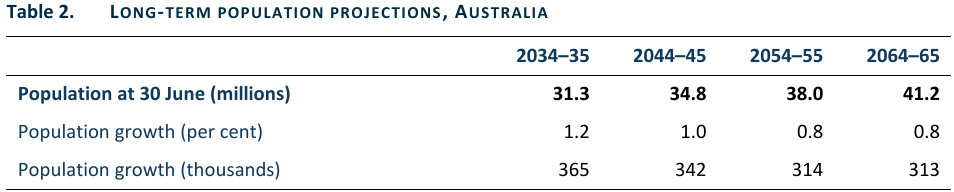

At the same time, the federal government has committed to increasing the nation’s population by 13.5 million over the next 40 years.

Source: The Centre for Population (December 2024)

Adding the equivalent of another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to Australia’s current population in only 40 years will require an unprecedented amount of investment in business, infrastructure, and housing to maintain the capital stock per person.

Achieving such unprecedented levels of investment will be impossible and will inevitably result in the economy suffering from further ‘capital shallowing’ and slower productivity growth.

In short, Australia is facing a low-productivity future, with declining living standards because we are hell-bent on committing energy policy suicide, deindustrialisation, and flooding the nation with vast volumes of low-skilled migrants.