The Australian’s Judith Sloan last week attacked the “shoddy” economic arguments used by those who favour large immigration numbers and open-border policies.

The canards identified by Sloan include the following:

- Recent high figures of net overseas migration (long-term arrivals minus long-term departures) are merely a catchup from the pause caused by Covid.

- The overall trend numbers are no different from the ones that the Morrison Coalition government had predicted.

- The problems in the housing market have nothing to do with the surge in the number of migrants.

- Any additional pressures on infrastructure and services are the result of poor planning, not because of the migrant intake.

- Any supposed loss of social cohesion is essentially the fault of those born in Australia and their intolerance to different cultures.

“Were a first-year economics student to serve up these falsehoods, they would fail”, argued sloan. “But open-border sympathisers/Big Australia advocates attempt to manipulate the numbers to push the line that there is nothing to see and there is no reason to reduce the migrant intake”.

Sloan described the ‘migration catch-up’ argument, which saw more than 1.1 million people arrive in just 30 months, as “a bit like saying the road was closed for a while and so no cars could get through. But with the road now opened, it was fine for the cars to massively exceed the speed limit”.

This argument also fails to acknowledge the significant impact of the pandemic on the supply side of the economy, particularly in housing construction. Thus, the economy’s absorptive capacity has been reduced.

Sloan labelled “absurd” the notion that huge migration volumes have little impact on housing and infrastructure.

“The reality is that no one is arguing for all migrant arrivals to cease. Rather, people are begging to see the net numbers much lower than the past several years”, Sloan argued, concluding that the migration system should also be focused on genuine skills “rather than simply ticking arbitrary boxes devised by bureaucrats”.

Last week’s howler from The Guardian’s Patrick Commins was a case in point of how left-leaning commentators tie themselves in knots trying to defend high immigration.

Recall that Commins unwittingly admitted that Australia’s high immigration lowers per capita GDP:

The chief economist at KPMG, Brendan Rynne, shares the consensus view among economists that migration has been good for the Australian economy…

Guardian Australia asked Rynne to model the impact of reducing population growth to just births minus deaths over the coming decade.

In this scenario, the population would grow at about 0.4% a year, instead of the predicted rate of 1.3% with migration.

As a result of this change, there would be 29 million residents by 2035, instead of 31.2 million.

That’s 2.2 million fewer people in this “no migration” scenario.

Unsurprisingly, the economy with closed borders is 2.4% smaller in a decade’s time than one with migration, the model shows.

Thus, per capita GDP, which is what matters for standards of living, will be significantly higher if there is no immigration. That is, Australia’s population would be smaller by 7.6% (i.e., 29.0m instead of 31.2m), whereas GDP would only be 2.4% smaller, resulting in a per capita GDP gain of around 5.2%.

Unsurprisingly, the lower migration and higher per capita GDP growth match higher wages and lower unemployment, according to Commins:

On the other hand, a smaller labour force means employers have to compete harder to attract workers.

That means wages would be 7.5% higher after 10 years of no migration, and the unemployment rate would be 0.2 percentage points lower than the base case…

Rynne said his modelling suggested “pulling back population growth to just natural increases for the next decade is not a great outcome for Australia”.

The data is unambiguous: lower immigration is a win-win-win for Australians, delivering higher per capita GDP, higher wages, and lower unemployment.

The most egregious claim from Commins is that lower immigration will actually drive home prices.

And house prices?

As mentioned, they are cumulatively 2.3% higher in a decade’s time than would have been under the base case of migration evolving as currently expected, the modelling shows.

To be clear: that’s not that prices will be 2.3% higher than they are today; that’s the additional price growth after a decade.

That’s because, Rynne says, the lower demand for housing is overwhelmed by the drop in the number of workers available to build homes.

This is Commins’ ‘jump the shark’ moment. More demand via population growth necessarily means higher home prices and rents. It is basic supply and demand.

But even if home prices were 2.3% higher with no immigration, housing would still become more affordable because wages would be 7.5% higher than otherwise.

Rynne’s claim that “the lower demand for housing is overwhelmed by the drop in the number of workers available to build homes” is also patently false.

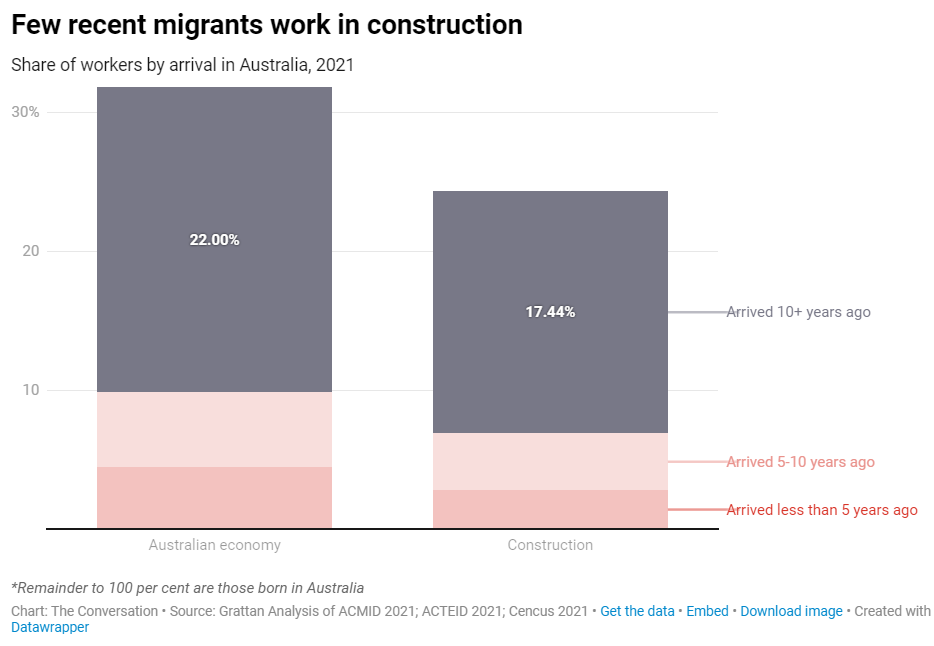

Data compiled by the pro-migration Grattan Institute shows that migrants are vastly underrepresented in the construction industry:

“Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”, Grattan reported.

A new report from the Australian National University’s Migration Hub also admitted that Australia’s immigration is worsening Australia’s housing and infrastructure shortages by dramatically lifting demand without adding to labour supply:

“In 2023-2024, the permanent programme delivered just 166 tradespeople, negligible against national needs. By contrast, more than 5,000 entered via the temporary skilled stream in 2024-2025”.

“Even this is insufficient to close the gap”.

Let’s get real: 430,500 net overseas migrants arrived in 2023-23 but only around 5,000 were tradespeople. Therefore, migrants have added far more to housing demand than supply.

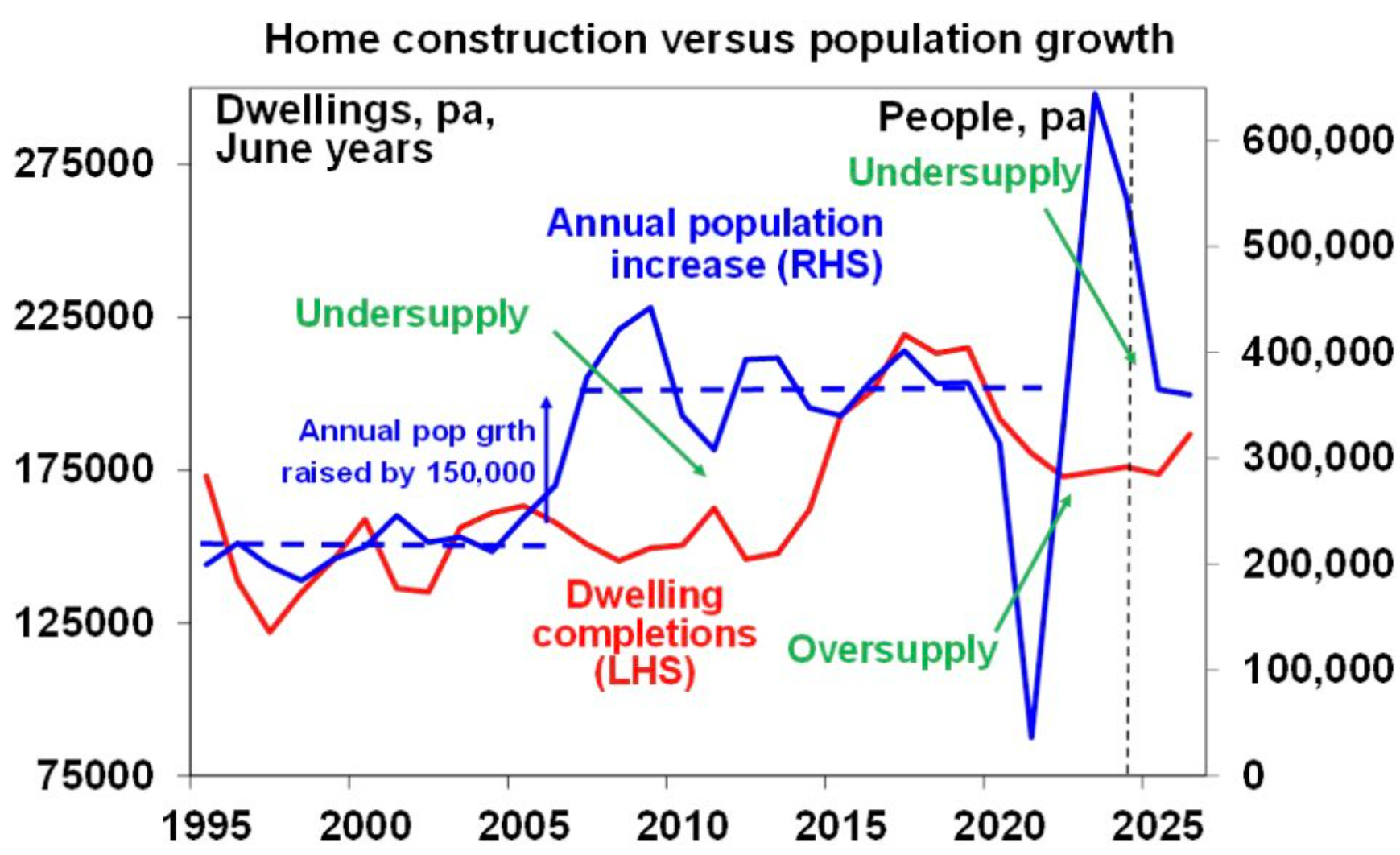

The following chart from AMP chief economist Shane Oliver illustrates that after immigration more than doubled and annual population growth jumped by 150,000, Australian housing became structurally undersupplied:

“Australian housing is chronically undersupplied”, Oliver wrote in July.

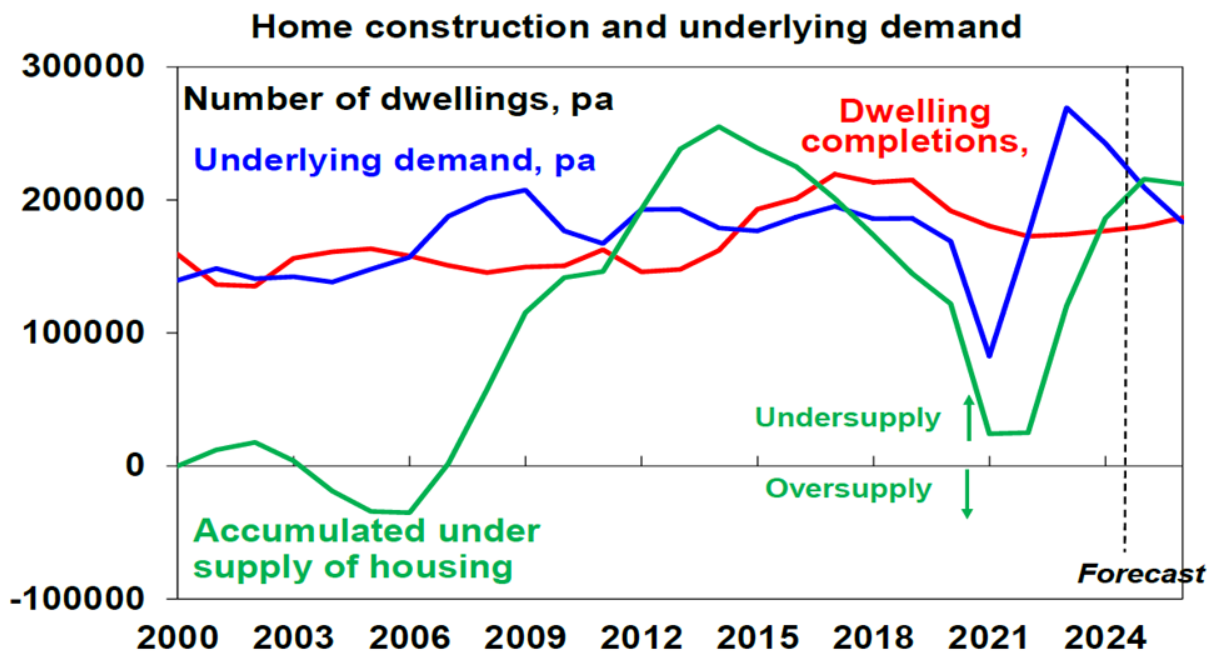

“This has been the case since the mid-2000s when immigration levels, and hence population growth, surged and the supply of new homes did not keep up. Our assessment is that the accumulated housing shortfall (the green line in the next chart) is around 200,000 dwellings at least and possibly 300,000 depending on what is assumed in terms of the number of people per household”.

“The economic reality is that when underlying population driven demand for housing exceeds its supply prices rise and that is what we have been seeing for the last twenty years. The capital gains tax discount, negative gearing and foreign demand may have played a role, but they have been a sideshow to this demand/supply imbalance”, Oliver wrote.

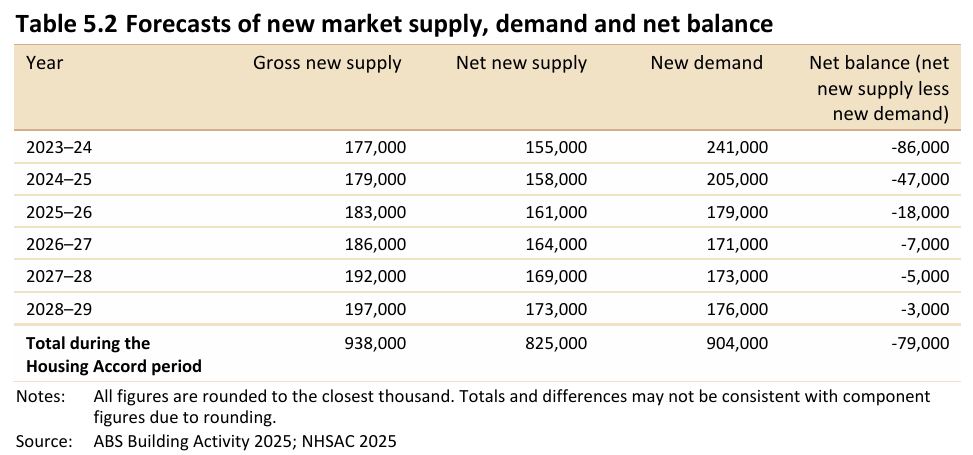

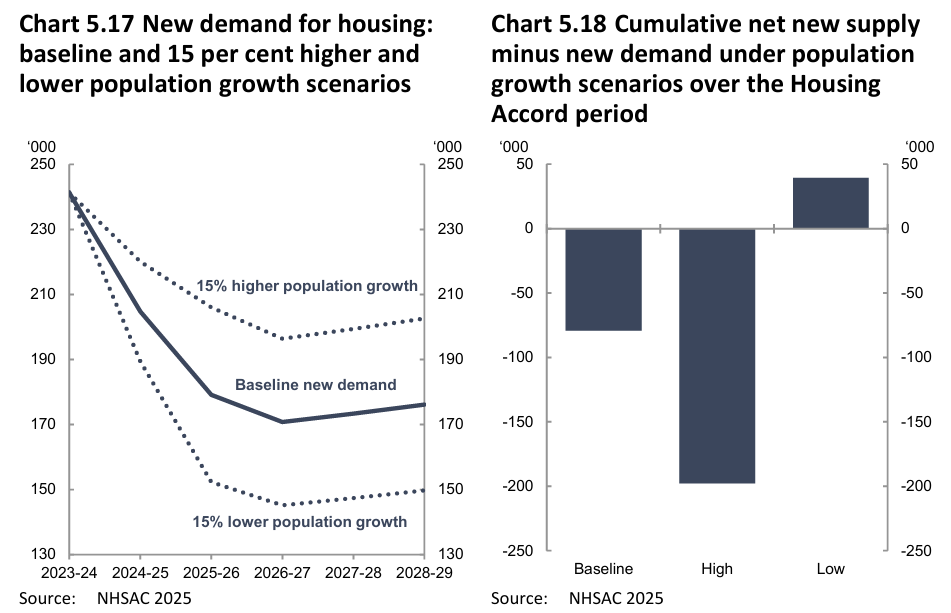

The latest State of the Housing System report from the federal government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) forecast that new housing supply will remain below population demand over the five-years to 2028-29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

The NHSAC report warned that ongoing strong immigration, combined with poor supply, will continue to pressure renters and result in more homelessness and overcrowding.

CBRE’s latest Apartment Vacancy and Rent Outlook, released last week, also forecast that population demand will continue to exceed supply over the next five years. As a result, the national capital city vacancy rate is projected by CBRE fall to a record low of 1.1% by 2030, down from 1.8% in 2025.

However, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis, buried at the back of its report, projected a surplus of around 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast.

Therefore, NHSAC’s report inferred that the primary solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to reduce net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

When will The Guardian admit that lowering immigration is the most effective policy to ‘solve’ the housing shortage?

Lower immigration directly benefits tenants by reducing rental inflation. It also benefits first-time buyers by making it easier to save a deposit (because they are paying less in rent) and curbing house price inflation.