“Stubborn empty nesters” refusing to downsize from their family-friendly homes have become Australia’s latest housing scapegoat.

In April, the Daily Telegraph’s Taylor Troeth cited research from Australian Seniors showing that two-thirds of empty nesters in NSW “were still living in large family homes with no plans to sell, despite research showing this could free up nearly 60,000 desperately needed properties across the country for younger Australians”.

Over the weekend, Cameron Micallef at News.com.au reported similar, citing a statement from RBA governor Michele Bullock stating that the reduction in the number of people per dwelling is fueling the mismatch between housing demand and supply.

“Yes, you’re absolutely right, it’s a supply issue and are we close to meeting it? All estimates suggest we are not”, Bullock said in an answer to a question from Wentworth independent MP Allegra Spender.

“Demand for housing is driven by new households being formed and the size of the household, and we’ve had declining household size”.

“Supply is an issue but demand is impacted not just by the number of new households being formed but the average household size”, Bullock said.

Micallef then cited analysis from Cotality head of research Eliza Owen claiming that Australia’s average household size has fallen from 2.6 to 2.5.

“I’d hate to say you have to live with people, as share houses or living with family is hard”, she said.

“But then I think of the other end of the spectrum, the empty nesters who don’t need all the bedrooms they have, but they don’t pay land tax and don’t have the family home counted in the asset pension test.

“Maybe it’s time to look at reviewing those incentives and encouraging downsizing”, Owen said.

Blaming people for occupying homes with spare bedrooms is the ultimate scapegoat and ignores the primary driver of the housing shortage.

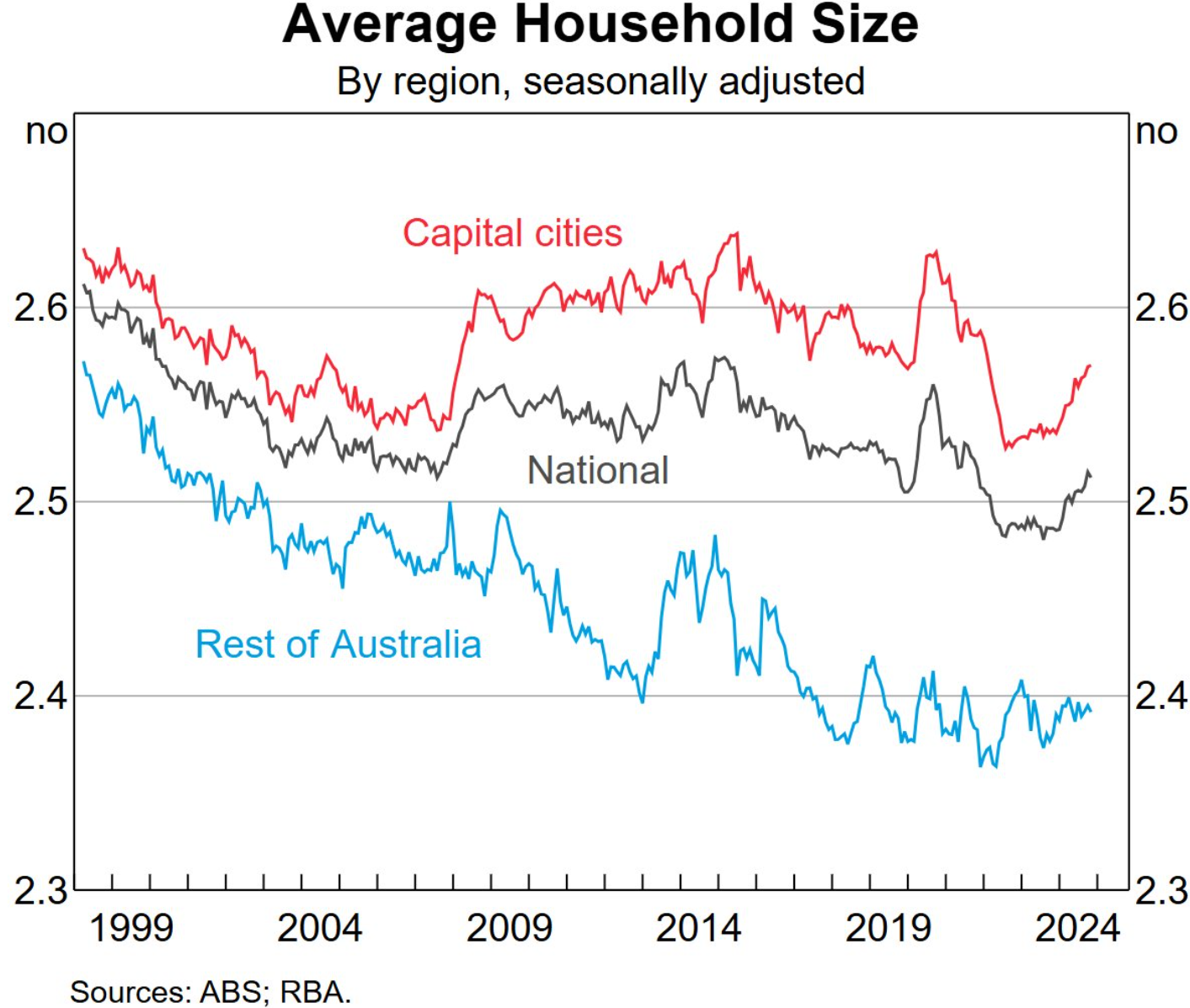

The RBA’s own data shows that the number of people per dwelling nationally is the same today as it was in the early 2000s before Australia’s historic rise in net overseas migration:

As shown above, the average household size across the combined capital cities is also significantly higher today than it was in the early 2000s.

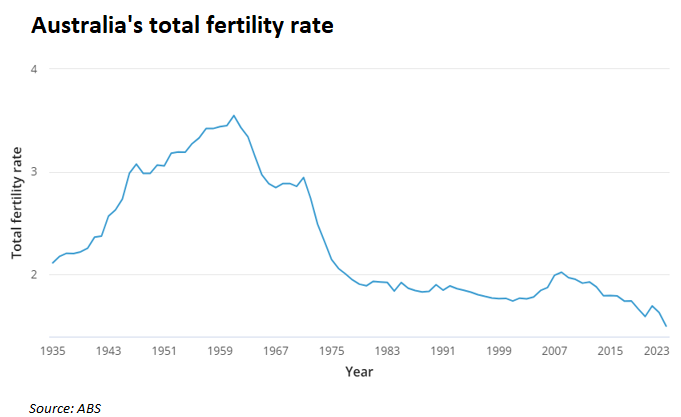

As tarric Brooker noted last week, Australia’s capital cities have lower fertility rates than the regions.

The rise in people per dwelling across the combined capital cities comes despite the collapse in Australia’s fertility rate to a record low of only 1.5 babies per woman:

A lower fertility rate and families having fewer children necessarily mean that the average household size should have fallen.

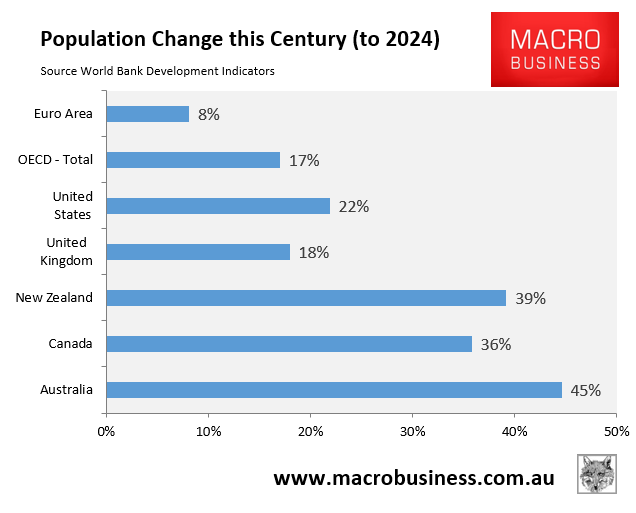

The reality is that Australia’s world-leading immigration-driven population growth is the primary driver of Australia’s housing shortage.

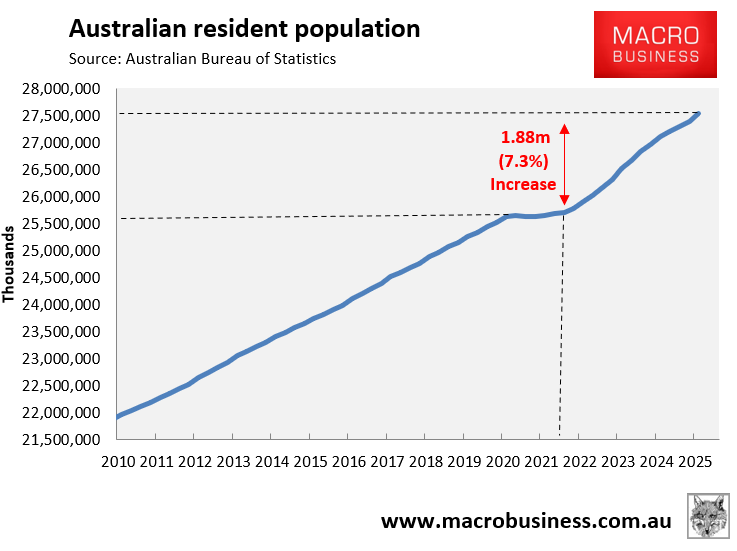

This month, the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) revealed that the nation’s population ballooned by 423,400 in the year to March—roughly equivalent to adding a Canberra.

In fact, Australia’s population grew by an astonishing 1.88 million (7.9%) between Q1 2021 and Q1 2025—equivalent to adding an Adelaide and Hobart to the nation’s population in just four years.

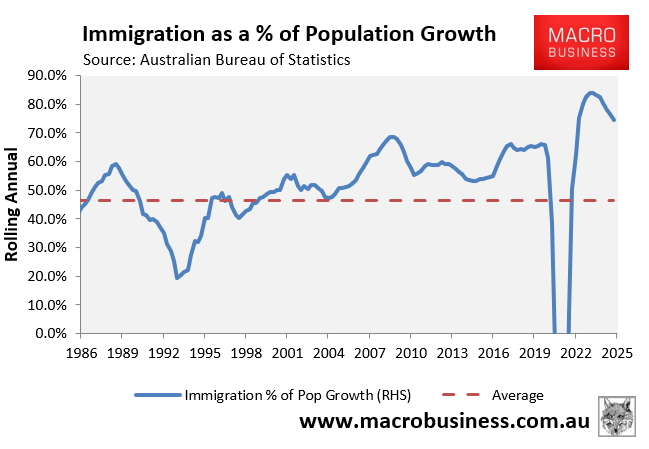

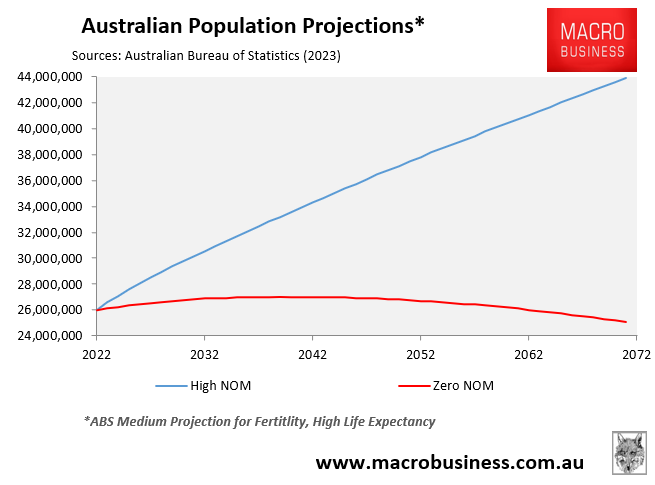

Net overseas migration directly has accounted for a growing share of Australia’s population growth. In fact, without immigration, Australia’s population would eventually decline (since migrants have children, counted as natural increase), given that the fertility rate is well below replacement.

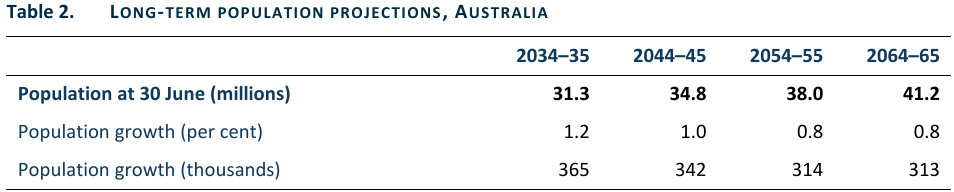

The official population forecast for Australia from the Centre for Population projects that Australia will grow by 3.8 million people to 31.3 million people over the coming decade. This means that by 2035, there will be 14% more people in Australia, equivalent to another Perth and Adelaide, who will need housing.

Source: Centre for Population

The longer-term projections from the Centre for Population have Australia’s population growing by 13.5 million, or roughly 50%, in the next 40 years, which is the equivalent of adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the current Australian population.

In summary, the primary cause of the nation’s housing shortage is excessive migration, given that it is the sole driver of the nation’s population growth— i.e., immediately as migrants step off the plane and subsequently as they have children.

Therefore, any concerns about Australia’s housing shortage should be directed at the federal government’s ‘Big Australia’ immigration policy and not at empty nesters.