Australian universities transform into greedy corporations

Over the past 20 years, Australian universities have evolved into revenue-driven corporations.

To summarise, the federal government and Australian universities created a framework to attract huge volumes of full-fee-paying overseas students by:

- The Australian government provided generous student visa work rights and the opportunity for permanent residency.

- Australian higher education institutions lowered admission and teaching standards.

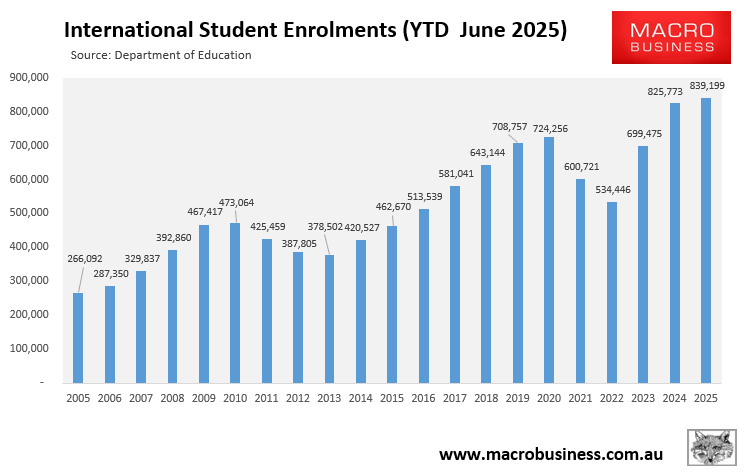

The number of international enrolments in Australian institutions has more than tripled since 2005:

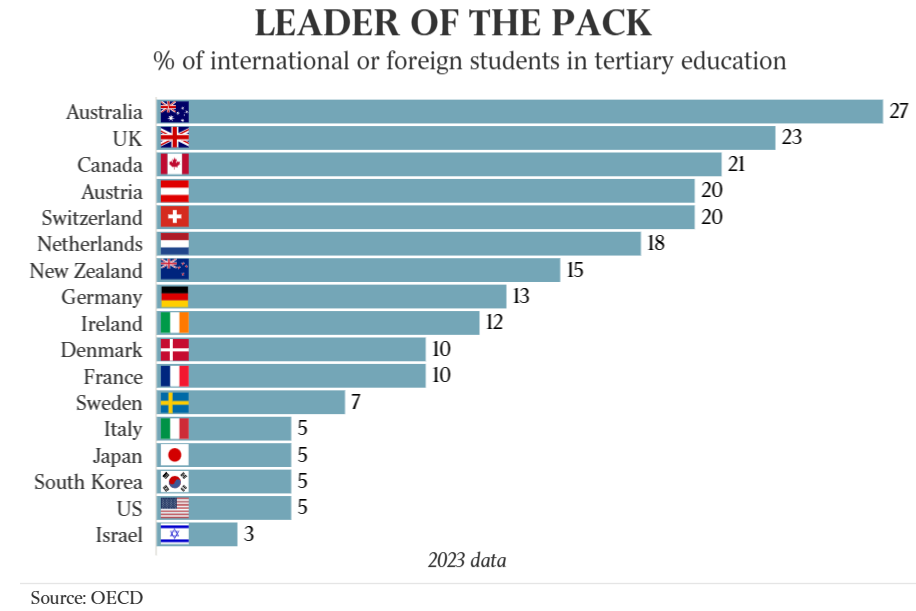

Australia now has the second-highest share of international enrolments in the world after Luxembourg:

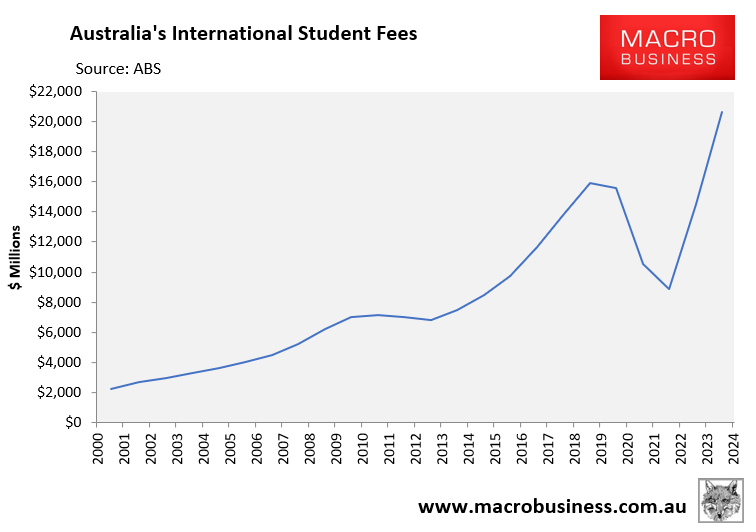

And fee revenue from international students has boomed:

The financial windfall from ballooning international student numbers was largely spent on flashy buildings and research aimed at propelling Australian universities up the global rankings, rather than on areas that improve the quality of education boost productivity.

Because a higher global ranking enhances a university’s reputation and implies quality, Australian institutions utilise these rankings as a marketing strategy to attract more overseas students while justifying higher tuition prices.

It is a phenomenal Ponzi scheme for Australian institutions. 1) Bring in plane loads of international students. 2) Channel fee revenue into research. 3) Improve the worldwide ranking. 4) Sell courses to more international students. 5. Rinse and repeat.

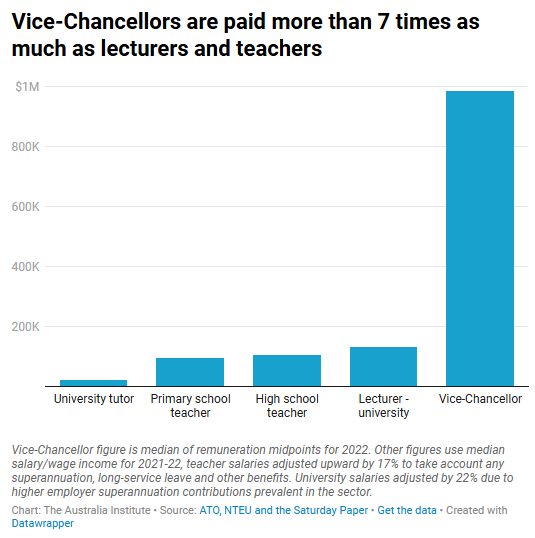

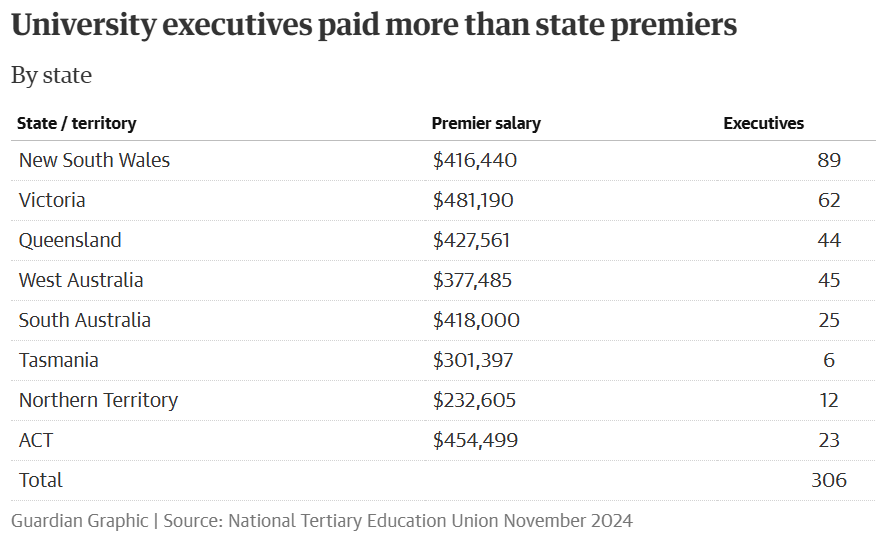

Vice-chancellors and senior executives rewarded themselves with salaries that are the highest in the world and dwarf those of other education professionals.

More than 300 Australian university executives earn more than state premiers.

Meanwhile, students have been treated like cattle, packed into generic, cookie-cutter courses.

Domestic students have also been required to help non-English speaking students in completing their courses through group assignments. Local students are frequently paired with internationals, resulting in domestic students performing the majority of the work, essentially serving as unpaid tutors and cross-subsidising international students’ grades.

In essence, universities and private colleges have privatised the benefits of record-high student enrolments, while other Australians, particularly domestic students and renters, have borne the costs.

Earlier this year, Dr Raffaele F. Ciriello, a Senior Lecturer in Business Information Systems at the University of Sydney, complained that corporate elites have hijacked Australian universities.

“Australian public universities are no longer run for education”, Ciriello said. “They have been taken over by a managerial elite that prioritises profits over academic integrity. Vice-chancellors earn more than the Prime Minister, with 16 of 41 making over $1 million annually”.

“Universities have become addicted to international student fees, which account for up to 40% of revenue”.

Ciriello added that the governing boards of universities have been overrun with corporate executives and consultants.

“A broken governance system entrenches this imbalance. Of 545 university governing body positions, only 137 are elected by staff, students or graduates, while corporate executives and consultants hold 143”, he said.

“Decisions prioritise financial growth over research and education, turning universities into corporate fiefdoms”.

Research from the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) likewise discovered that corporate heavyweights are co-opting university governing councils, resulting in a “circular system of patronage” that maintains underpaying employees and overpaying executives.

The Senate is currently conducting an inquiry into the quality of governance at Australia’s universities, with the use of consultants being called into question by a submission to the inquiry.

University of Wollongong accounting professor Corinne Cortese stated in her submission that an estimated $734 million had been spent on consulting firms by universities in 2023 at the same time as partners from EY, PwC, KPMG, McKinsey, Deloitte and BCG sat on the governing bodies of about one in three institutions.

Cortese claims that more members of university councils and senates have backgrounds in consulting firms than possess deep experience in higher education, excluding the members elected by staff and students.

“Many university council members also have substantive affiliations with Australia’s largest corporations, all of which have close ties to the big four, adding to the intricacy of the networks of interest that can permeate university councils”, Cortese wrote in her submission.

“Consultancies and their interests are represented on all sides of the higher education table. They are on university councils, they are advising on the direction of universities, they are engaged to conduct that lead to the advice provided, they provide the assurance for the contents of these reviews, and they are intricately tied to the business networks that make up the majority of the remaining council members”.

Australia has created a system that rewards university executives with large salaries for effectively transforming their institutions into low-quality, high-volume immigration mills.

Pedagogical standards have been destroyed, with academics prohibited from failing international students because it would undermine their high-volume business model:

Local students have been forced to carry internationals through their courses via group assignments and cheating by international students is rife:

Tutorials at Australian universities have been conducted in foreign languages:

Many fake ‘ghost colleges’ have also been set up as migration scams.

Everyone can see that vested interests have corrupted higher education in Australia.

Rather than continually lowering standards to lure more international students of doubtful quality to Australia, policymakers should aim to recruit a much smaller pool of excellent (genuine) students.

This could be achieved with the following types of reforms:

- Significantly increasing English-language standards and requiring prospective students to complete entrance examinations before being permitted to study in Australia.

- Significantly increasing financial requirements, including requiring funds to be paid into an escrow account before arriving in Australia.

- Reducing the number of hours that international students are allowed to work and severing the direct link between study, work, and permanent residency.

- Allowing only top-of-class graduates to receive graduate visas.

- Because Australian universities are non-profit enterprises that do not pay taxes, imposing a levy on international students to ensure that Australians receive a financial return from the trade.

Universities should also be required to provide on-campus housing for international students in proportion to the number of enrolments to reduce pressure on the private rental market.

Australia’s international education sector must aim for quality over quantity.