Australia must slash international student numbers

The AFR’s education editor, Julie Hare, published an alarmist article on the tiny reduction in international student enrolments, which she labelled a “plunge”.

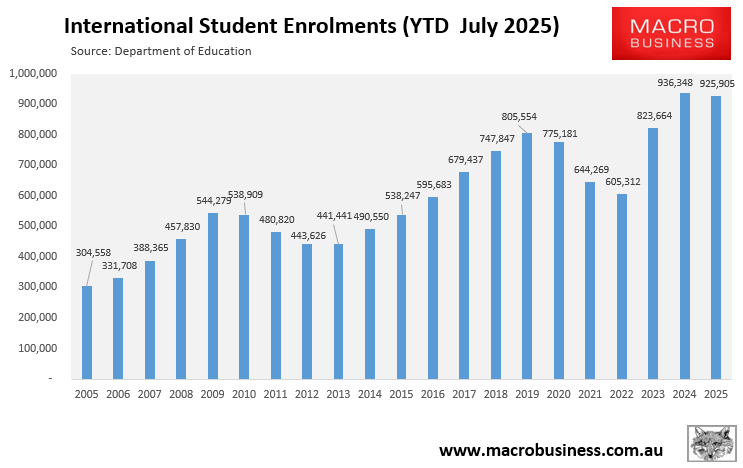

The Department of Education data showed that there were 925,905 total international student enrolments in the year to July 2025, down a tiny 1.1% from last year’s record high of 936,348 enrolments.

However, enrolments over the first seven months of 2025 were up a hefty 14.9% from the pre-pandemic peak of 805,554 enrolments in 2019.

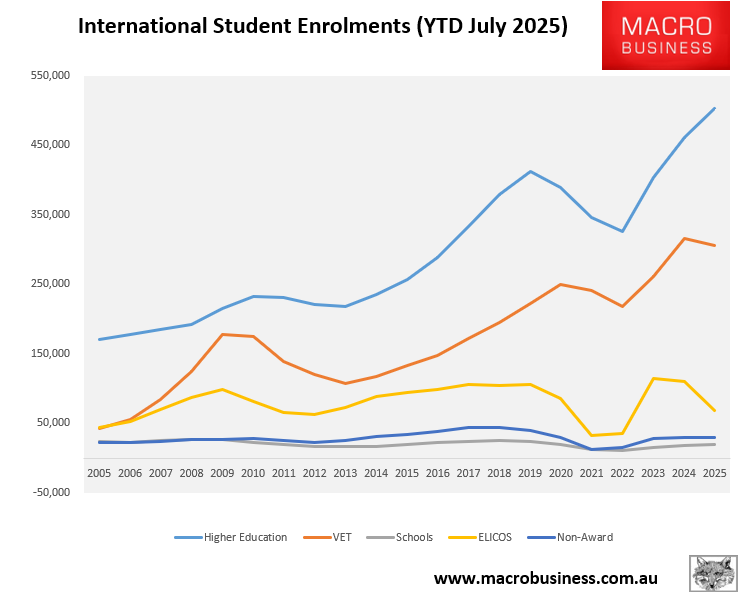

Higher Education (university) enrolments hit a record high of 503,071. However, this was more than offset by a small fall in VET enrolments and a large decline in ELICOS enrolments.

However, as some international students study more than one course in a reported year, the total number of international students in Australia was recorded by the Department of education at 791,146 as of July.

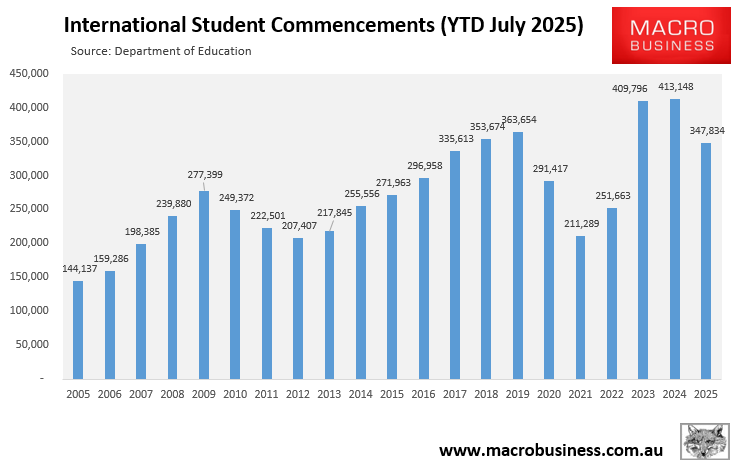

While the stock of international students is a whisker below its all-time high, the flow of students via commencements has returned to around pre-pandemic levels.

There were 347,834 international student commencements in the year to July 2025, down 15.8% from last year’s peak of 413,148.

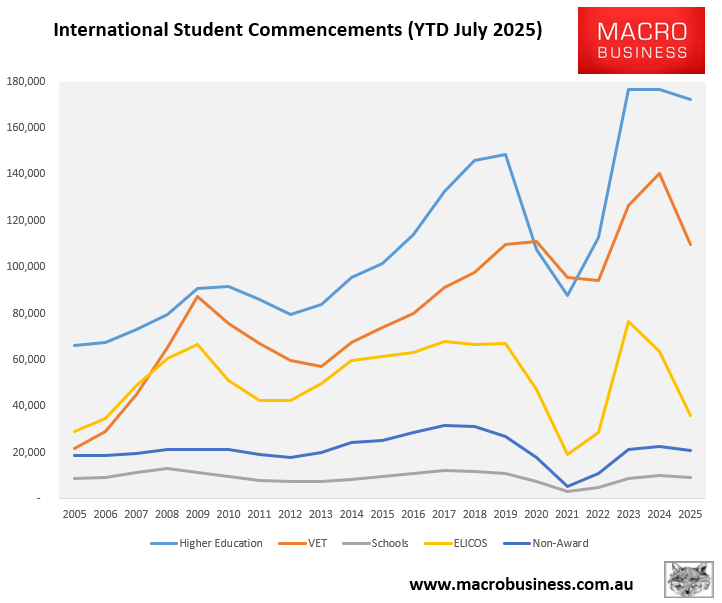

University commencements were only down moderately from their peak, whereas VET and ELICOS commencements have fallen sharply.

Despite international student numbers remaining just shy of their all-time peak and well above pre-pandemic levels, the usual industry lobbyists decried the tiny fall as ‘doom and gloom’.

Phil Honeywood, chief executive of the International Education Association of Australia, told The AFR that for the “first time in living memory every sector is down” compared to the previous year.

“Clearly, the world’s highest non-refundable visa application fee is doing the government’s work for it”, Honeywood said. “English language colleges are closing down at an alarming rate, and we are doing damage to brand Australia, particularly in our own region”.

This is a hilarious statement from Honeywood who in 2023 labelled Australia’s international education system a “Ponzi scheme” and a “race to the bottom” for recruiting non-genuine students through migration channels (see here and here).

Enrolments today are significantly higher than they were in 2023. So what is Honeywood’s problem?

Despite the fact that total university enrolments are at a record high and new university enrolments are just shy of their peak, Luke Sheehy, chief executive of peak group Universities Australia, complained that flows were falling short of the government’s expanded allocations.

“The government’s decision to allocate more than 12 per cent growth next year for international numbers at universities in an acknowledgement of both the tenuous financial position of the sector – especially in regional areas – and the importance of the industry to the economy”, Sheehy said.

“To stay competitive, Australia needs stable, welcoming policy settings that give students confidence to choose us”.

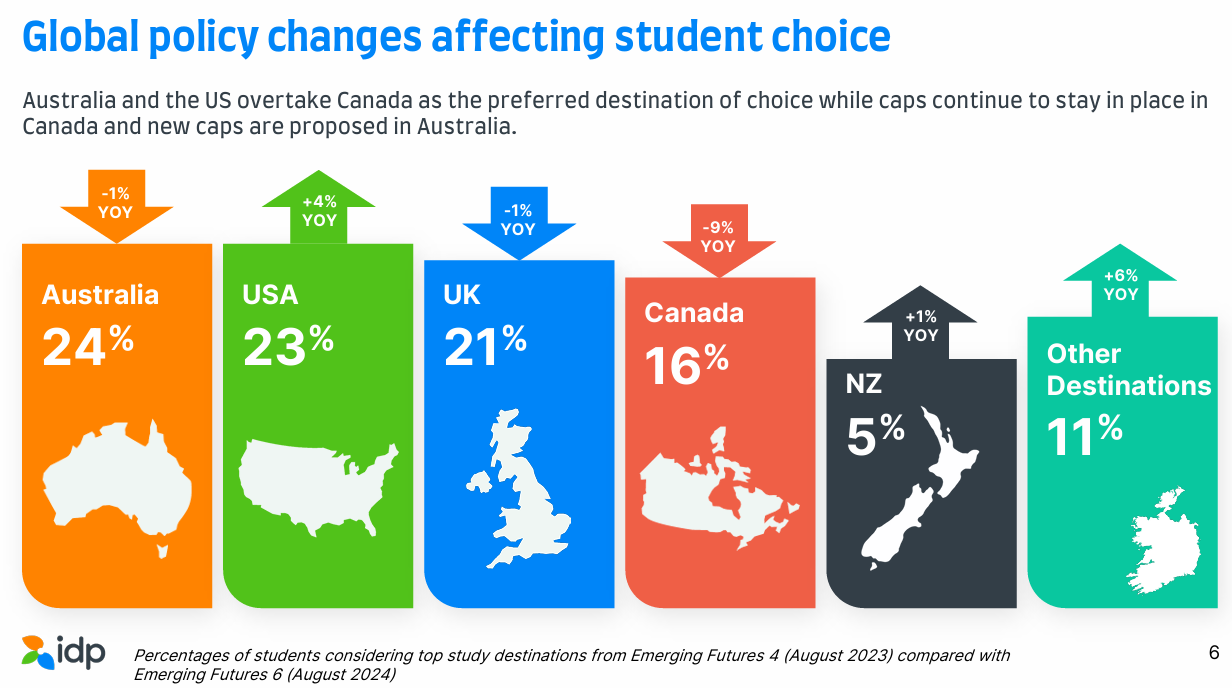

Sheehy’s special pleading ignores the findings of the most recent IDP Emerging Futures survey, which showed that Australia remained the top study destination for potential overseas students.

Research by Dutch analytics company Studyportals also found that Australia was the only major destination to register an increase in overseas student demand over the first quarter of 2025.

The reality is that we need to reduce the absurd concentration of international students in Australia.

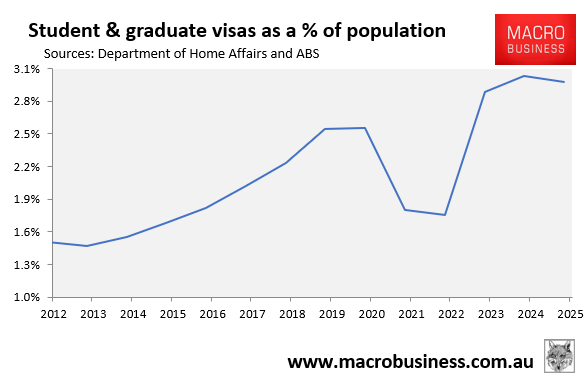

The latest temporary visa data from the Department of Home Affairs shows that student and graduate visa holders comprised 3% of Australia’s population—almost one in 30 people—in the June quarter of 2025. This was up from 2.6% at the pre-pandemic peak and double the 1.5% share in 2012.

There are also around 100,000 prospective or former students on temporary bridging visas, which are not counted above.

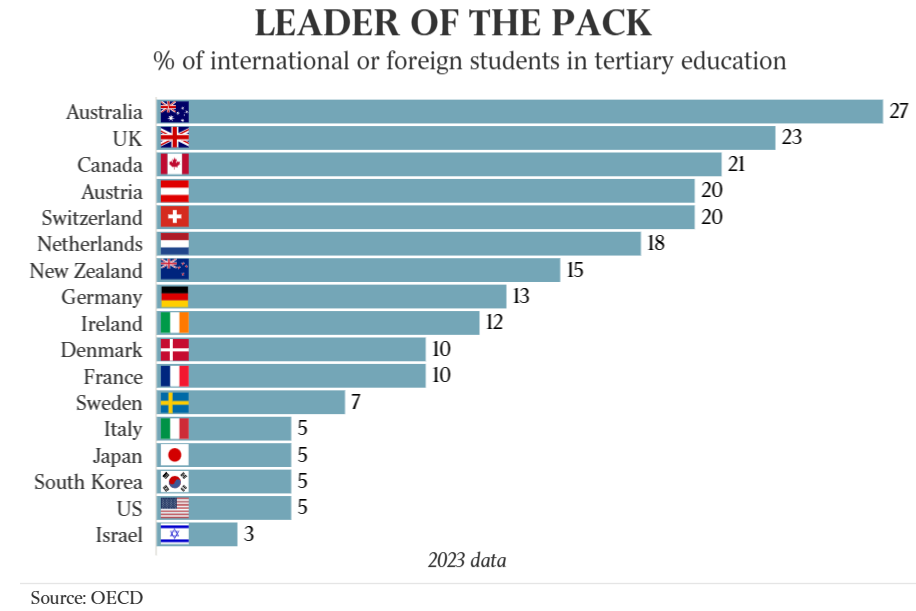

Last week, The Australian posted the following chart showing that “international students account for 27% of enrolments in Australian universities—a bigger share than every other country bar Luxembourg, where half the students are foreigners”.

“Only 5% of university students in the US come from other countries, compared to 23% in the UK, 21% in Canada and 20% in Switzerland”.

“In Germany, just 10% of university students are foreigners, in Italy and Japan it’s 5% of enrolments, and in New Zealand 15%”, The Australian reported.

The world record increase in international students has raised serious concerns about the erosion of standards at Australian institutions.

Concerns include mass cheating across Australia’s universities:

Academics working at Australia’s universities are being prevented from failing poorly performing international students because it risks revenue:

Tutorials at leading Australian universities are being held in foreign languages:

Many fake ‘ghost colleges’ have also been set up as migration scams.

It is patently obvious that vested interests have corrupted higher education in Australia.

Rather than continually lowering standards to lure more international students of doubtful quality to Australia, policymakers should aim to recruit a much smaller pool of excellent (genuine) students.

The government must force the international education sector to aim for quality over quantity via the following types of reforms:

- Significantly increasing English-language standards and requiring prospective students to complete entrance examinations before being permitted to study in Australia.

- Significantly increasing financial requirements, including requiring funds to be paid into an escrow account before arriving in Australia.

- Reducing the number of hours that international students are allowed to work and severing the direct link between study, work, and permanent residency.

- Allowing only top-of-class graduates to receive graduate visas.

- Because Australian universities are non-profit enterprises that do not pay taxes, imposing a levy on international students to ensure that Australians receive a financial return from the trade.

Universities should also be required to provide on-campus housing for international students in proportion to the number of enrolments to reduce pressure on the private rental market.