Earlier this year, Matt Bell of The Australian wrote an article based on the Hays 2025 Skills Report, saying that Australia was experiencing a skills crisis, with businesses struggling to recruit staff with the necessary abilities.

Similar views have been expressed throughout the lead-up to the federal government’s productivity summit, even though Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA) data shows that there are an abundance of applicants per job, suggesting that concerns surrounding labour shortages are overblown.

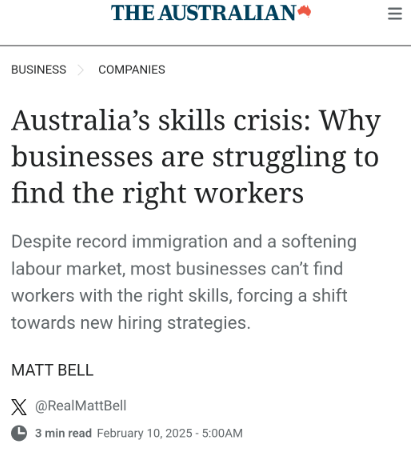

At the economy-wide level, there were 29.3 applications per vacancy, 9.4 qualified applicants per vacancy and 4 suitable applicants per vacancy:

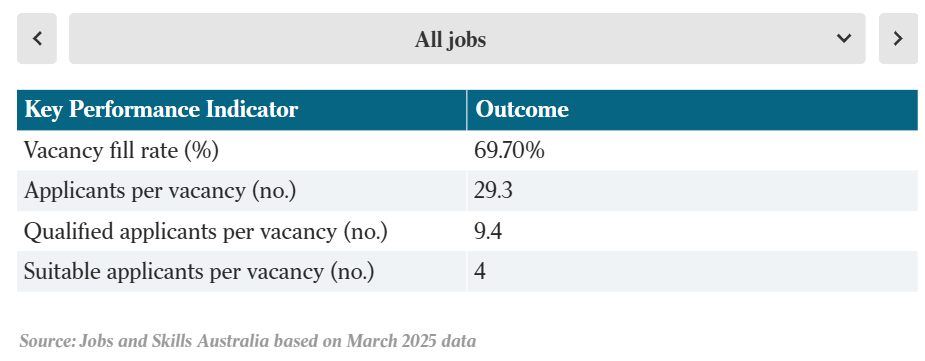

As shown below by Alex Joiner, chief economist from IFM Investors, Australia is awash with low-skilled workers, yet continues to experience a relatively severe shortage of high-skilled workers:

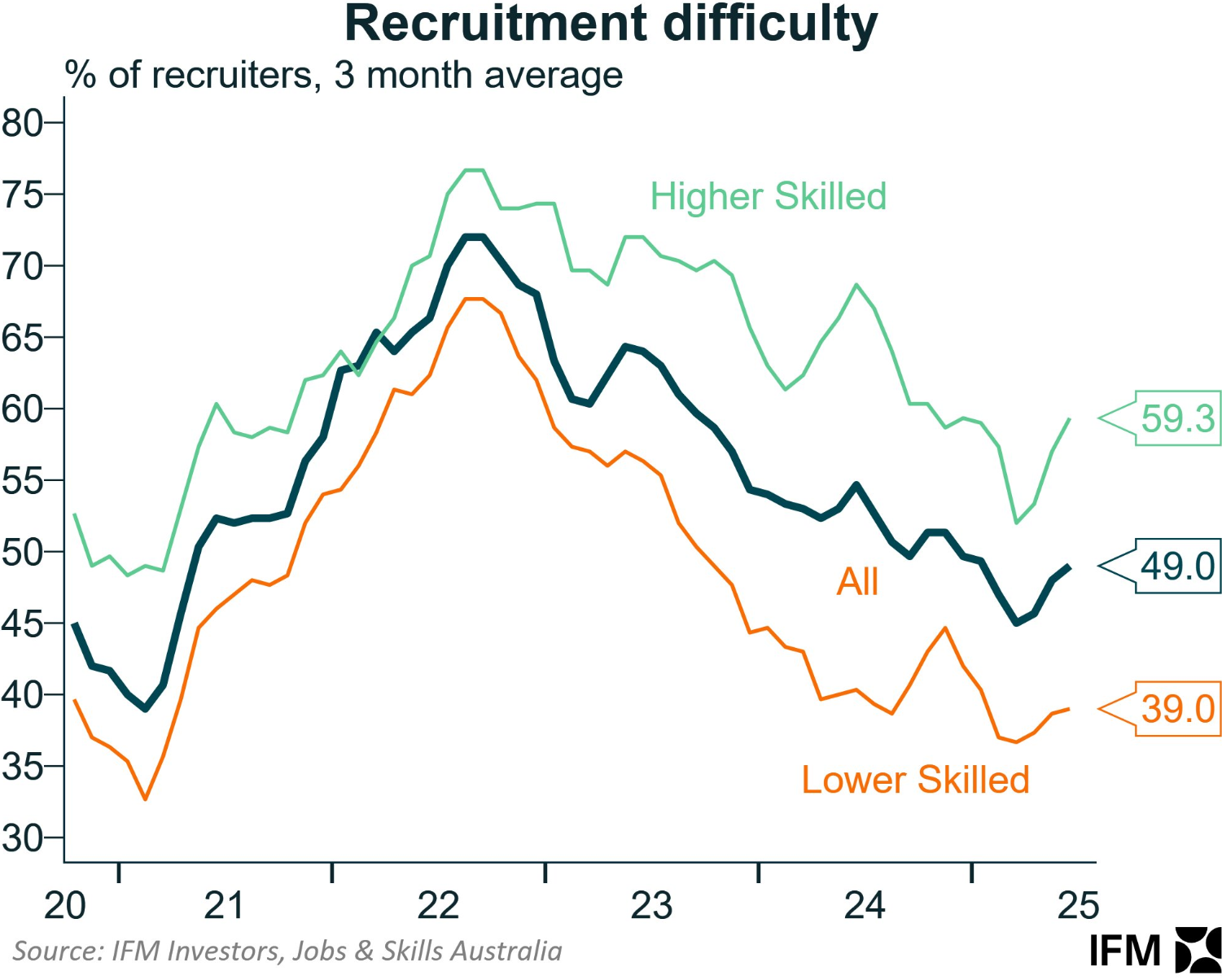

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised by this outcome given Joiner added the following chart showing that the overwhelming majority of net overseas migration has been unskilled:

The Albanese government this month announced that it has raised the planning level for international students by 25,000 to 295,000 for 2026.

Labor also watered down the visa system by weakening English-language requirements.

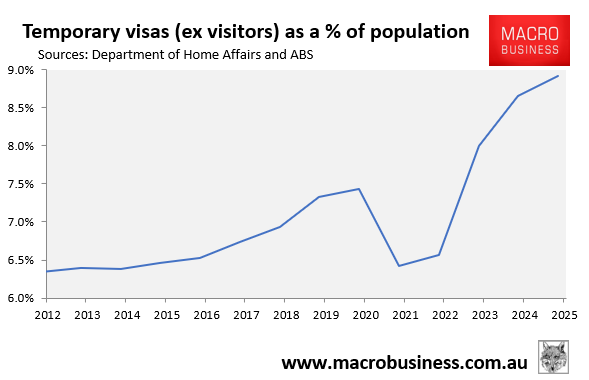

As a result, Australia’s international student and temporary visa numbers—which are already the highest in the advanced world relative to our population—will inevitably increase.

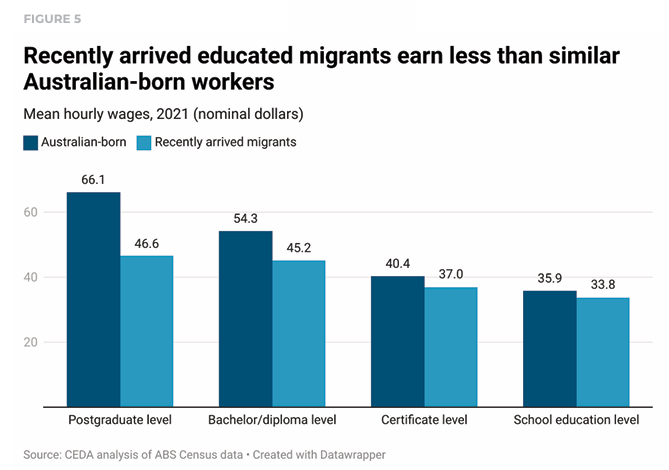

The Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) examined the most recent census and discovered that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migrants are consistently underemployed and underpaid.

“Recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers, and this has worsened over time”, CEDA senior economist Andrew Barker said.

“Many still work in jobs beneath their skill level, despite often having been selected precisely for the experience and knowledge they bring”.

The CEDA analysis also explained that Australia’s migration system is contributing to the country’s poor productivity growth.

“Labour productivity and wages are closely linked, indicating that migrant labour is not being used as productively as it could be”, the report said.

“This decade, migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”.

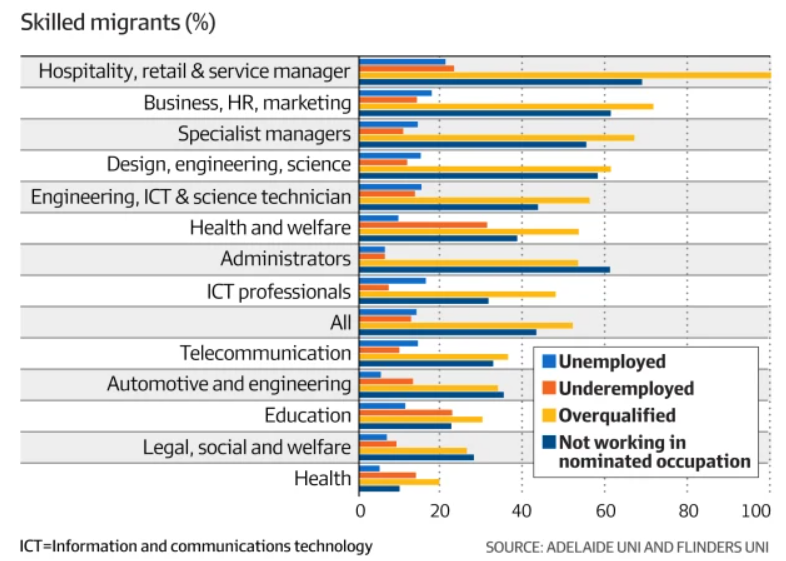

According to Adelaide University’s George Tan, 43% of skilled migrants who entered via the state-sponsored visa system did not work in the occupation they claimed.

The majority of skilled migrants were overqualified for positions in retail, hospitality, and service management.

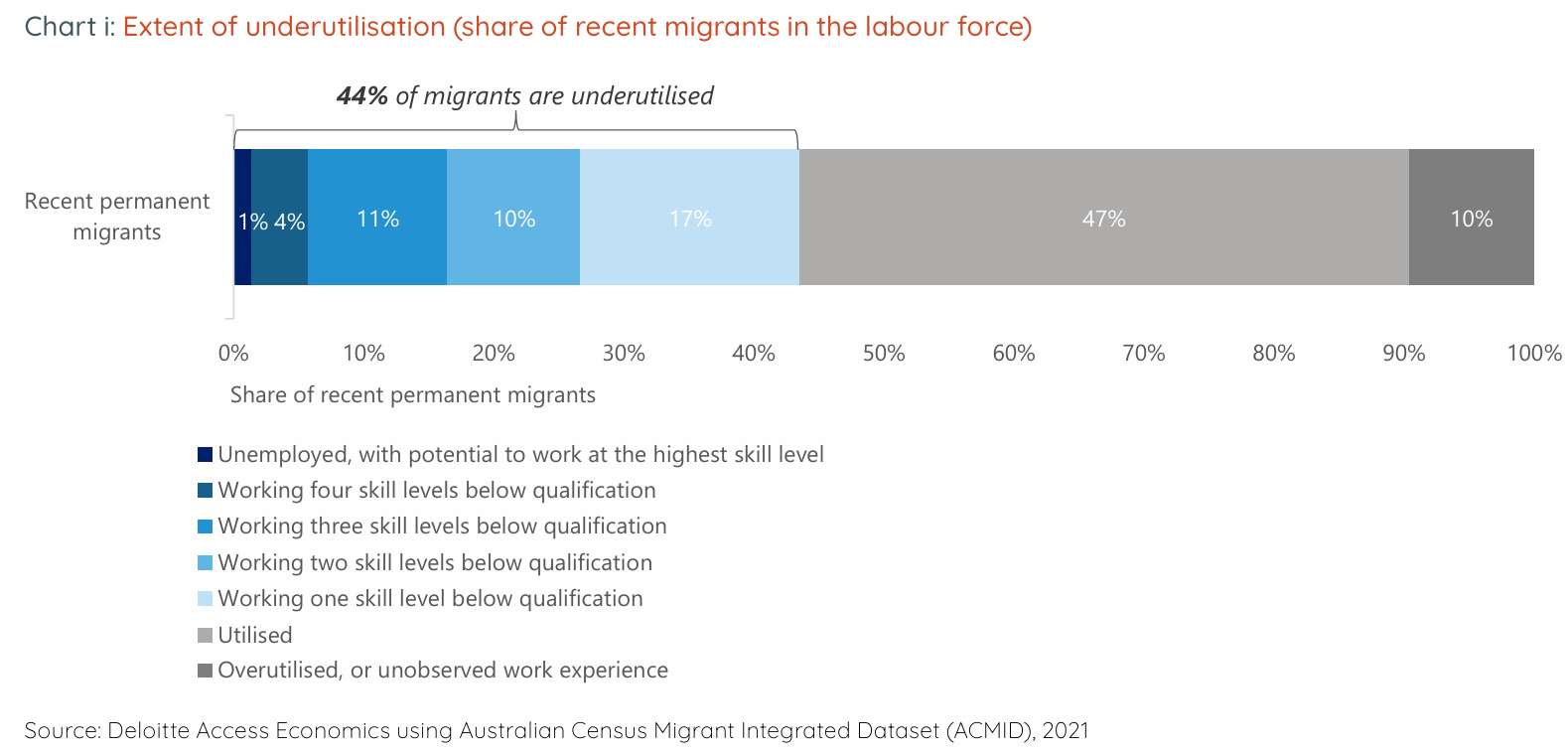

Deloitte Access Economics found that 44% (621,000) of permanent migrants in Australia worked in jobs below their skill level in 2023. The majority of these underemployed migrants came through the skilled stream.

On average, among those permanent migrants who arrived in Australia in the last 15 years, almost half (44%) are working in an occupation at a lower-skill level than is commensurate with their qualifications (Chart 1).

This means in 2024, there are more than 621,000 permanent migrants living in Australia who are underutilised and not working to their full potential.

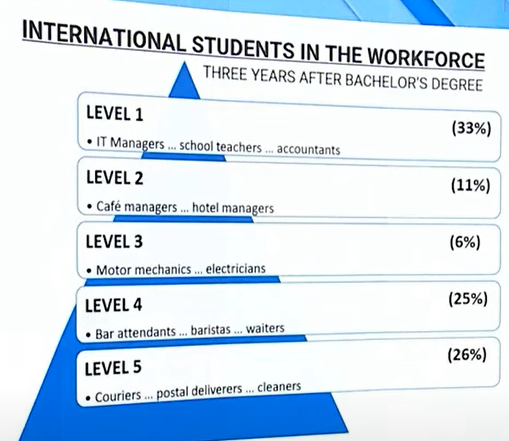

According to the federal government’s 2023 Migration Review, 51% of foreign-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees worked in unskilled employment three years after graduation.

Source: Migration Review, 2023.

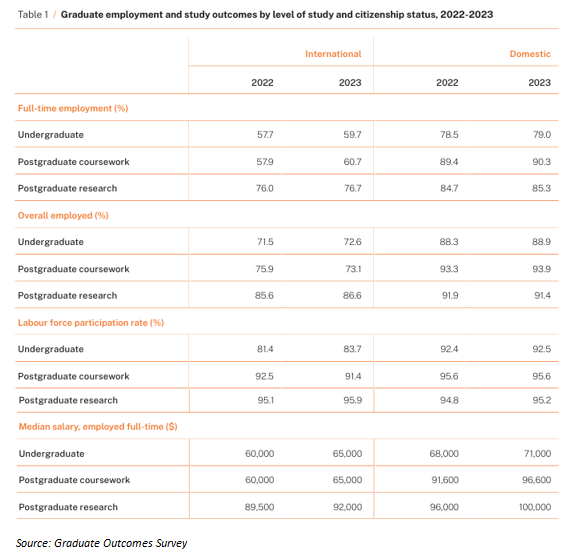

The Graduate Outcome Survey has consistently found that international graduates earn significantly less than locally born graduates and have poorer labour market outcomes.

What additional proof is required to demonstrate that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migration system is failing to produce the desired results?

Mass immigration has failed to deliver the necessary skills, worsening infrastructure and housing shortages, as well as environmental deterioration.

‘Capital Shallowing’ has harmed Australia’s productivity by reducing the amount of capital investment per person.

Australians have effectively had the worst of both worlds—recessionary levels of business investment that have been diluted by strong population growth via immigration.

The optimal solution is to operate a smaller, higher-skilled, and higher-income migration system.

The wage floor for all skilled visas should be set significantly higher than the existing median full-time salary of roughly $90,000. All skilled visas should be employer-sponsored, with qualified migrants required to begin working in their field of competence immediately.

All retirement visas, including parental and ‘golden’ tickets, should be cancelled.

Entry standards and financial requirements for other temporary visas, such as student visas, should be dramatically tightened to focus on quality over quantity. And only top-of-class international students should receive graduate visas.

Sadly, the Albanese government has taken the opposite approach, lifting the intake of international students by 25,000 and watering down English-language proficiency rules.

As a result, the quality of Australia’s migration system will degrade further, skills shortages will persist, and productivity growth and living standards will continue to deteriorate.