According to Cotality (formerly CoreLogic), the average home in Australia is now valued at around $1,020,000. This makes Australian housing among the most expensive in the world.

Australian housing was valued at 4.14 times the size of the Australian economy in Q1 2025, nearly double its value in the 1990s. By way of comparison, the US housing stock is valued at only 1.6 times the US economy.

Australia’s housing stock was valued at nearly $400,000 per person in Q1 2025, and in real terms, it has more than tripled in value over the past 30 years.

The surge in average home values above $1 million has notionally made Australians some of the wealthiest people on earth.

The latest UBS Global Wealth Report, for example, ranked Australian households second in the world on median net wealth, behind Luxembourg.

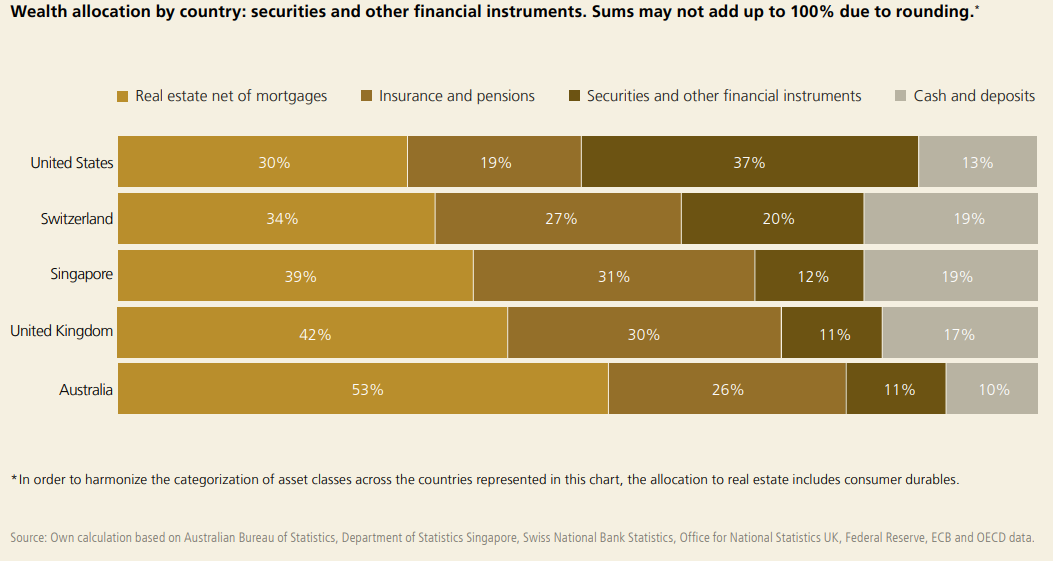

However, unlike other nations, Australians hold most of their wealth in their overpriced homes, rather than financial assets like shares.

Source: UBS Global Wealth Report 2025

In this regard, much of Australia’s wealth is illusionary, and expensive housing is actually choking the economy and making the nation worse off.

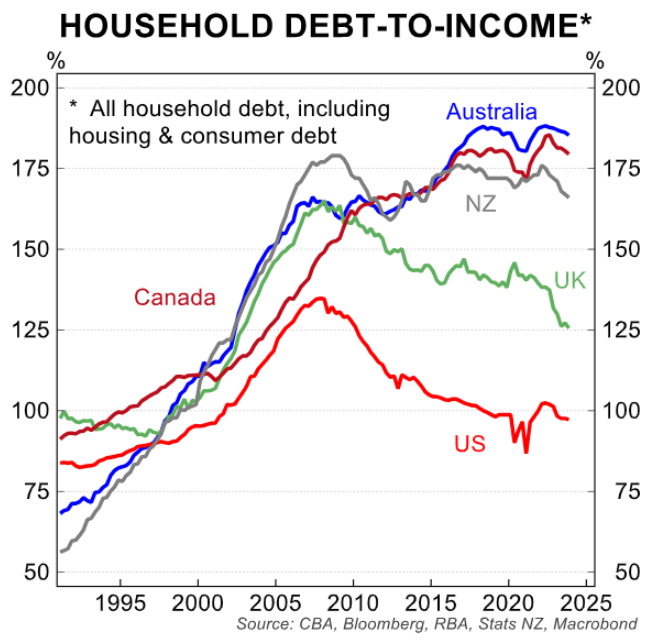

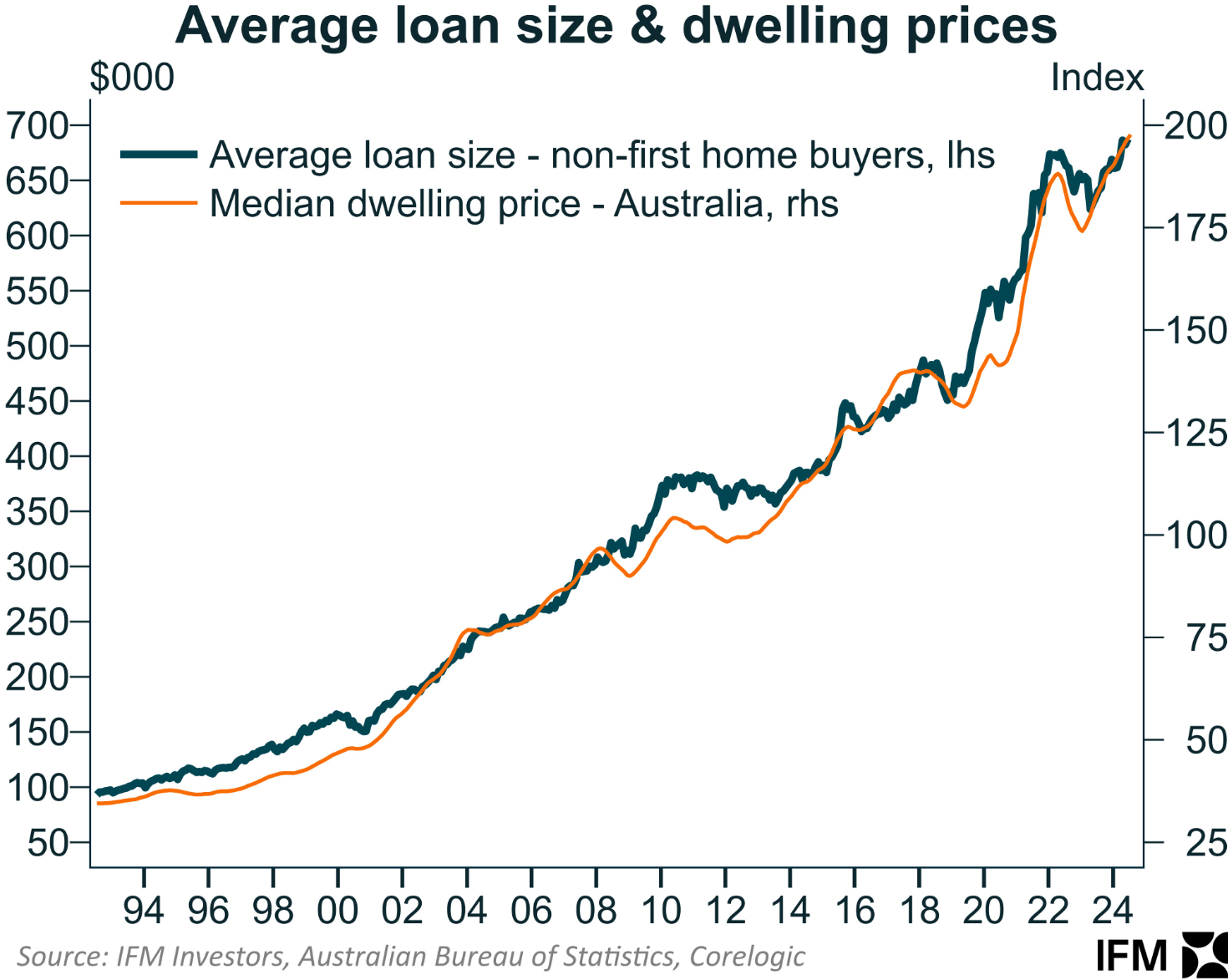

Australian households carry some of the world’s highest debt loads, most of which is mortgage debt.

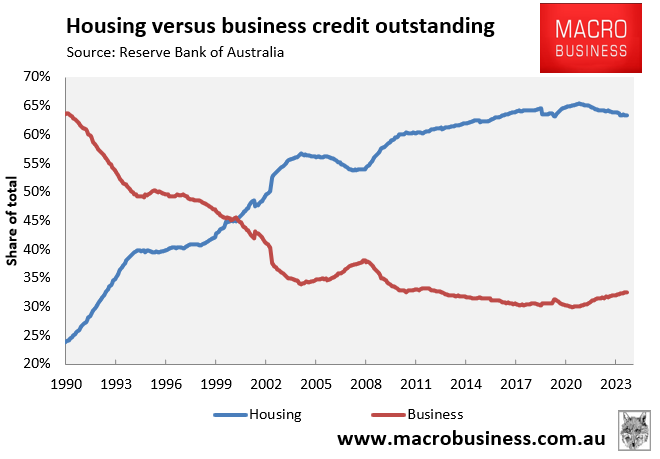

The rush of capital into housing has starved businesses of investment and lowered Australia’s productivity. Australia’s banks have become overly focused on home lending at the expense of lending to productive businesses.

In 1990, roughly two-thirds of bank lending was for businesses, with mortgages accounting for only around a quarter of bank lending.

Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with over two-thirds of bank lending for housing and barely one-third for businesses.

Five of the 10 most valuable companies on the ASX are banks: ANZ, CBA, National Australia Bank, Westpac and Macquarie Group.

It’s a stark contrast to the US sharemarket, where innovative technology companies take out the top seven positions: Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google owner Alphabet, Facebook owner Meta and Broadcom.

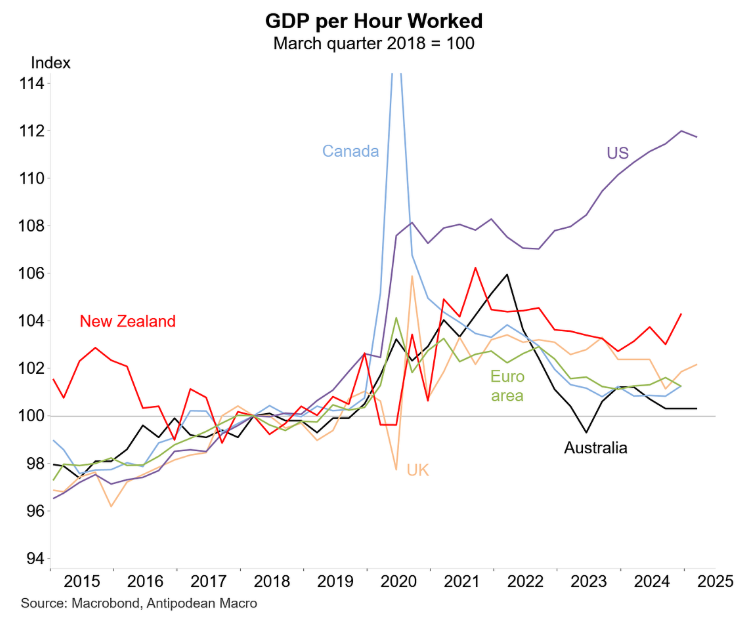

Productivity is booming in the tech-savvy US and stagnant in Australia.

Australians would benefit lower home prices:

It is perverse that despite being among the wealthiest households in the world, Australians are struggling financially.

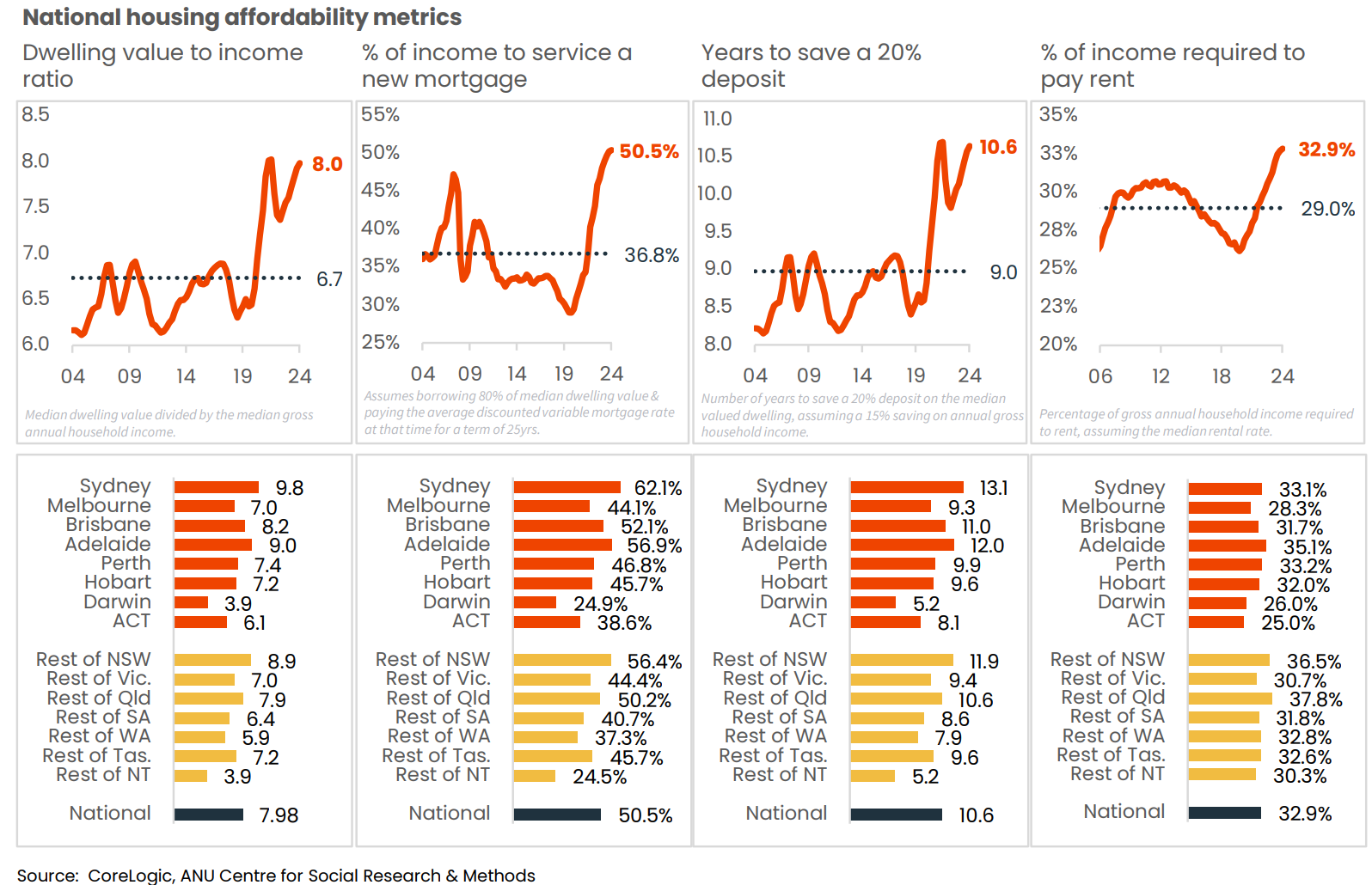

Many Australians are buckling under the weight of mortgage and rent repayments, which, according to Cotality, were sucking up a record share of income at the end of 2024.

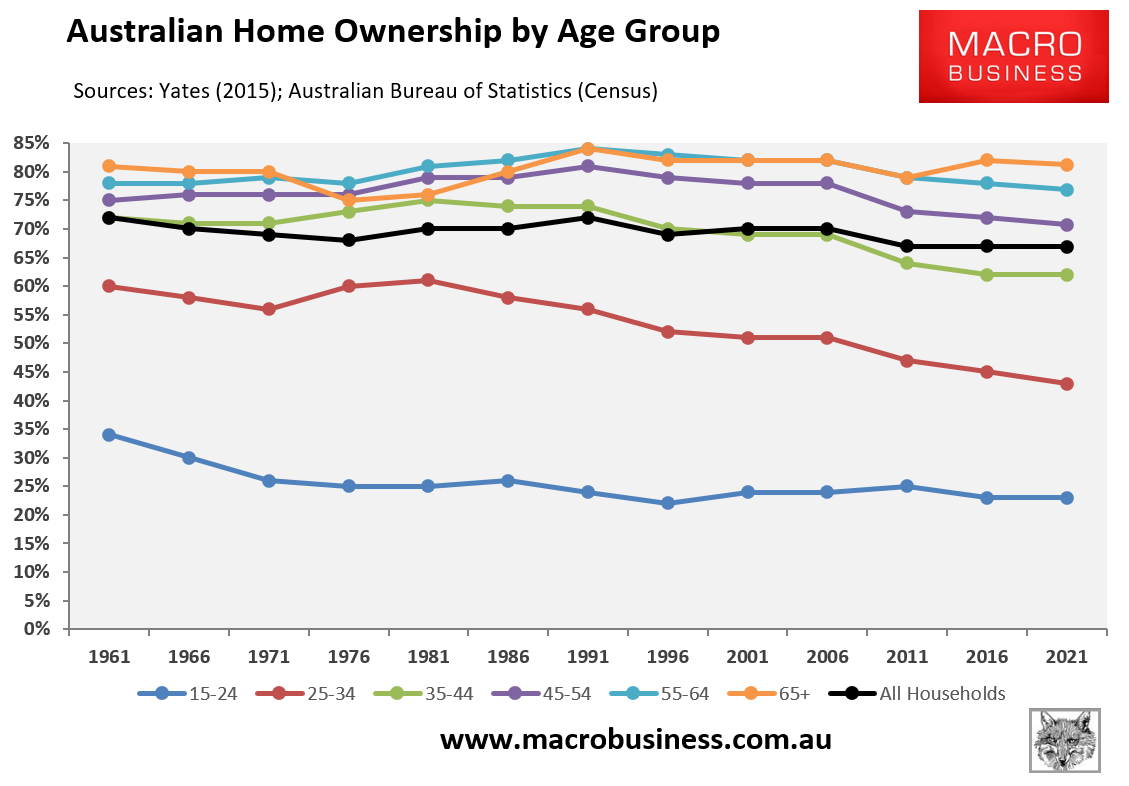

Given that housing affordability is at an all-time low and our younger generations are unable to buy a home without parental financial assistance or subsidies, how can Australian households be considered the world’s second-wealthiest?

Australians would be wealthier if the average home were valued at $500,000 instead of $1 million, and household debt were 90% of income rather than 180%.

A home, whether it costs $500,000 or $2 million, serves the same function.

Australia would be a considerably more egalitarian society, and we would be financially better off if our homes cost half as much as they do now, with half the debt.

In 1991, Australia’s home ownership rate was about 5% higher than today, homes cost around 3 times incomes (versus 8 times today), and household debt was 70% of income versus 180% of income today. Banks also lent two-thirds to businesses and only one-quarter to mortgages.

Objectively, households were better off in 1991 than today. We also had a far more balanced and diversified economy in 1991 than today.

Australia’s high property prices negatively impact our children, grandchildren, and future generations by forcing them to pay significantly more for shelter than is necessary, making them worse off.

Higher housing “wealth” is meaningless to the vast majority of people who live in their homes rather than own investment property.

The economy would also be more balanced and productive if it channeled capital into businesses rather than into inflating home values. Australia’s $11.4 trillion housing stock represents a gross misallocation of capital.

The Albanese government will make the situation worse:

Sadly, the Albanese government this week brought forward its policy of allowing all first-time home buyers to purchase a property with only a 5% deposit to 1 October. Under the scheme, the government (taxpayers) will guarantee 15% of borrowers’ loans.

The Treasury predicts that 70,000 homes will be purchased through the scheme in the next 12 months and claims it will only increase home values by around half a percent after six years.

Treasury’s 0.5% growth forecast is delusional. The impact will be far greater.

Modelling released this week by Lateral Economics concluded that the 5% deposit scheme will result in house prices rising by between 3.5% and 6.6% nationally within its first year. Property prices for the first-home segment are projected to rise by as much as 9.9% within 12 months as a result of the policy.

The past 25 years have proven that whenever governments provide demand-side policy stimulus, be it first home owner grants and subsidies or 5% deposit schemes, they have proven self-defeating from an affordability perspective, ultimately resulting in larger mortgages and higher home prices.

Labor’s policy, combined with lower interest rates, will further increase household debt and property prices, as well as divert more of the nation’s capital into non-productive housing.

Again, the average dwelling in Australia is currently valued at more than $1 million. So, the last thing the housing market needs is more policy stimulus.

If the Albanese government genuinely wanted to improve housing affordability, it would take the pressure off rents and prices by cutting immigration.

Instead, the government expanded the student visa intake by 25,000 and watered down English-language requirements.

As a result, population demand will continue to run ahead of supply, worsening overall housing affordability.

I discussed these issues on this week’s Treasury of Common Sense on Radio 2GB/4BC: