The ABS released its official population data for Q4 2024, which showed that both immigration and population growth continue to ease back from record highs.

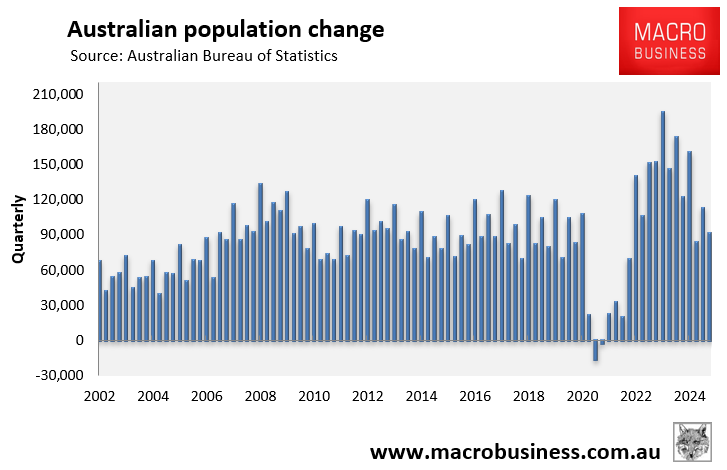

In Q4 2024, Australia’s population grew by 91,100, down from 121,600 in the same quarter the year before.

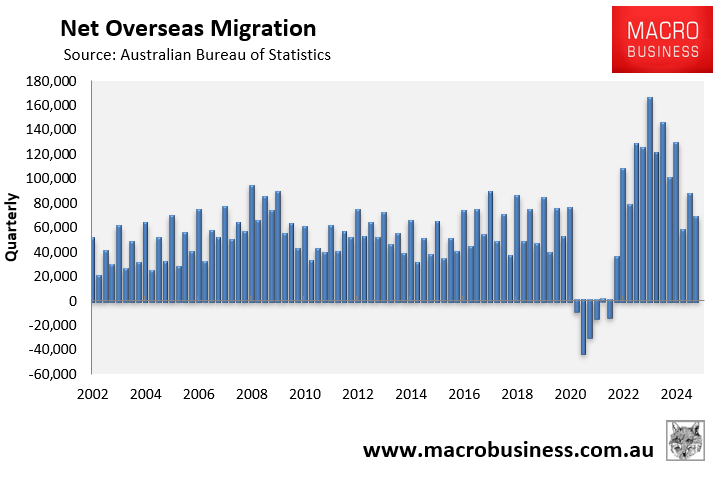

Net overseas migration (NOM) of 68,000, down from 99,500 in Q4 2023, drove the population growth.

Annually, Australia’s population grew by 445,900 in 2024 (basically a Canberra), driven by NOM of 340,600.

NOM remained above the pre-pandemic peak of 315,700 in Q4 2008, accounting for 76% of total population growth.

The slowing in immigration and population growth is obviously great news, as it will reduce pressure on the housing market, which is currently experiencing historically poor affordability to purchase and rent.

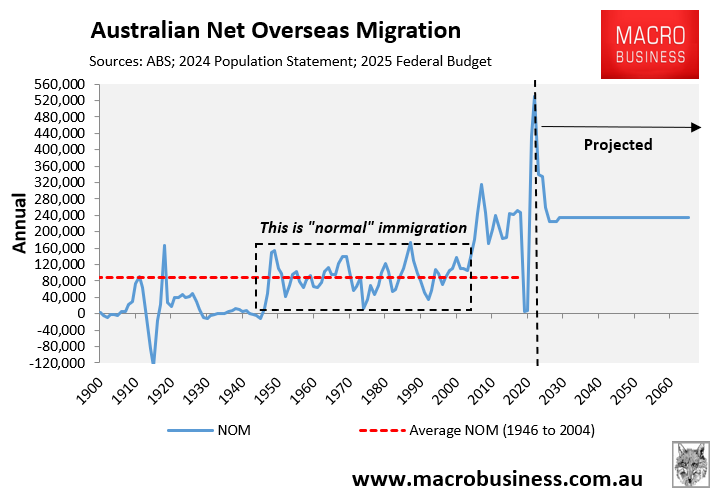

The budget forecasts have immigration easing back to pre-pandemic levels by FY27, and it is then forecast to remain at 235,000 for the next four decades.

The problem is, this projected immigration level of 235,000 is far too high and will ensure that Australia’s housing crisis remains permanent. We only need to look at the last 20 years of data.

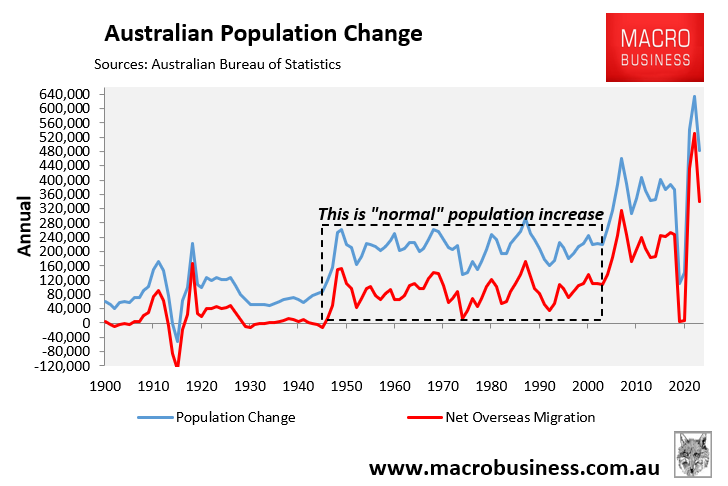

Australia’s population growth jumped after the Big Australia policy was introduced, and NOM more than doubled from 2005.

Australia’s NOM averaged 90,000 annually in the 60 years following World War 2 and only exceeded 150,000 in two of those years.

In the 20 years from 2005, Australia’s NOM has averaged 231,000 annually, a 156% increase on the 60-year average following World War 2.

As a result, Australia’s population has grown by 8.7 million (46%) this century, the strongest growth in the developed world.

This extreme population growth is why housing and infrastructure supply have not kept pace with demand, resulting in housing crises and declining livability in our major cities.

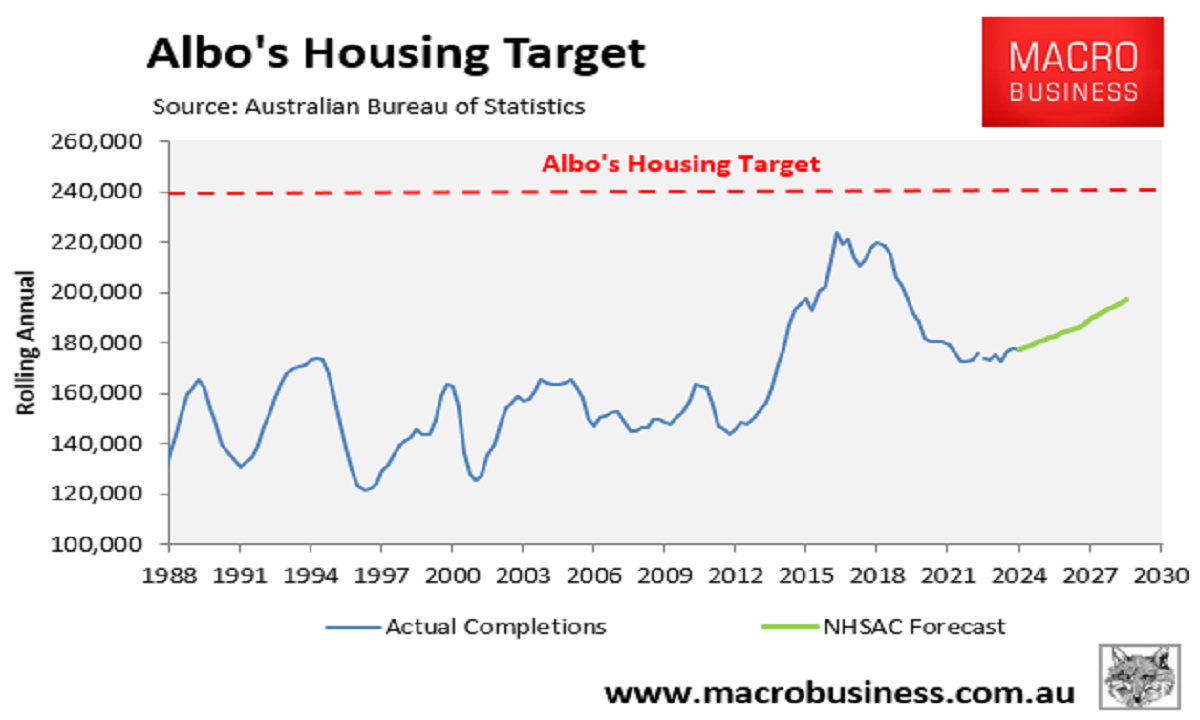

Australia’s housing shortage is forecast to worsen:

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver recently estimated that Australia’s cumulative housing shortage is between 200,000 and 300,000 homes.

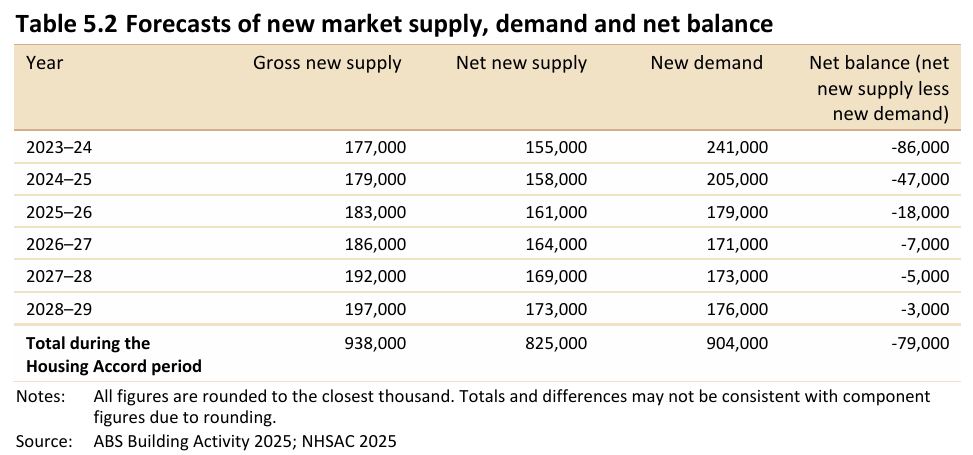

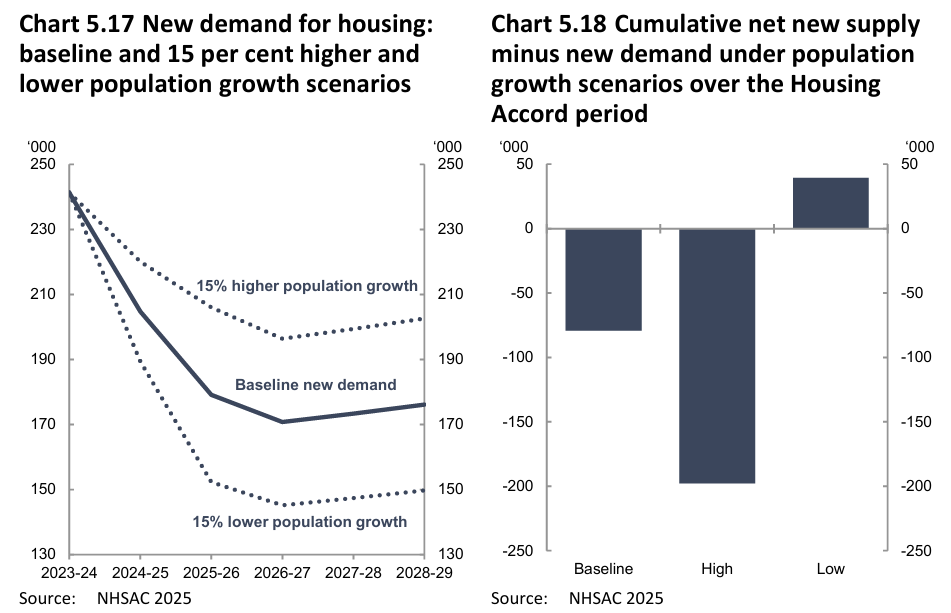

The National Housing Supply & Affordability Council (NHSAC)’s latest State of the Housing System report, released last month, forecast that Australia’s housing shortage will worsen as population demand continues to exceed supply.

NHSAC forecast that only 938,000 dwellings will be built nationwide by mid-2029, which is 262,000 (22%) dwellings short of Labor’s target of 1.2 million new homes over five years.

As a result, Australia’s cumulative housing shortage will increase by 79,000 homes over five years.

However, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of around 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast.

NHSAC’s report, therefore, shows that the primary solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to cut net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Australia’s housing shortage will become permanent:

Sadly, the federal government has no genuine intention to solve the housing crisis.

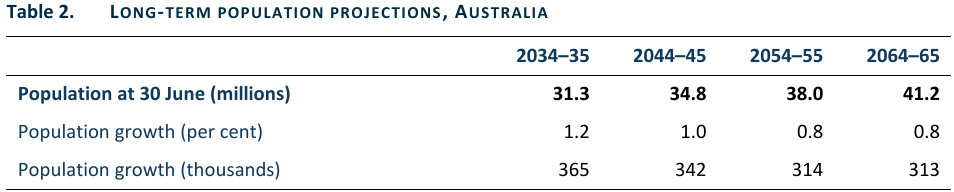

The Australian Treasury’s Centre for Population projects that Australia’s population will grow by 13.5 million in 40 years, equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the current population.

In 40 years, we would need to replicate all the current homes and infrastructure in these three large cities. That is an impossible task.

It took Australia 185 years to reach a population of 13.5 million in 1973. Yet, we are officially projected to grow by this amount in the next 40 years!

Once again, the primary solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to reduce net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Everything else is window dressing.