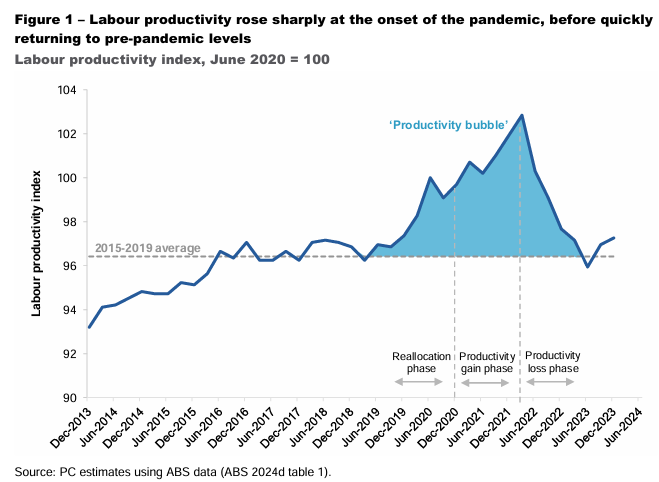

The Productivity Commission (PC) released a research report entitled “Productivity before and after COVID-19”, which claims that Australia experienced a ‘productivity bubble’ during the pandemic, in which measured labour productivity rose to a record high between January 2020 and March 2022 before returning to pre-pandemic levels in June 2023.

The PC claims that Australia is now “back to the stagnant status quo”.

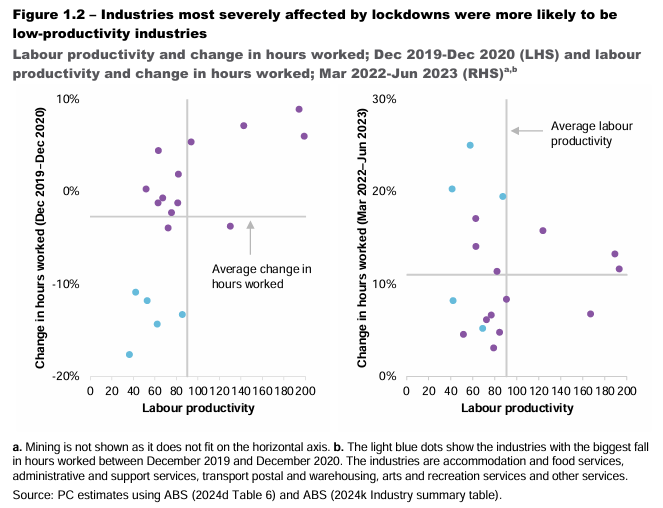

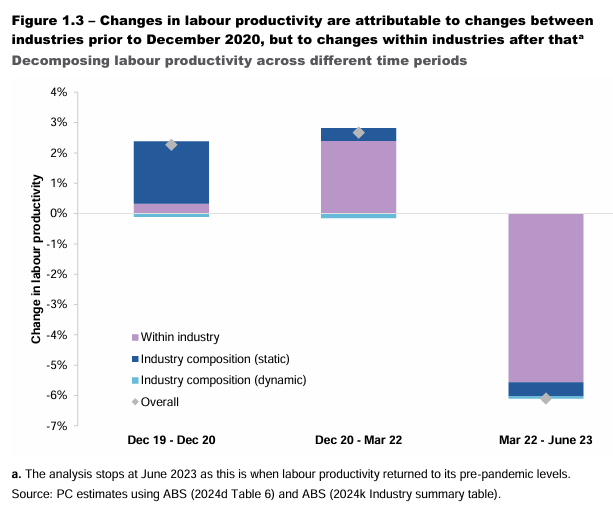

According to the PC, Australia’s productivity lifted during the initial ‘reallocation’ phase, which lasted from December 2019 to December 2020, as lockdowns relocated workers away from businesses with lower labour productivity, such as accommodation and food services, and towards more productive sectors.

Labour productivity continued to rise during the second phase, from December 2020 to March 2022, as output per worker improved. As lockdowns ended, the labour market gradually rebounded, with output increasing faster than employment.

These productivity gains faded during the bubble’s ‘productivity loss’ phase, which lasted from June 2022 to June 2023, when the labour market expanded.

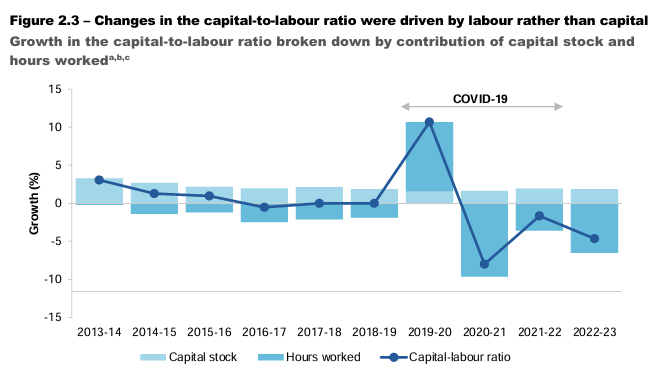

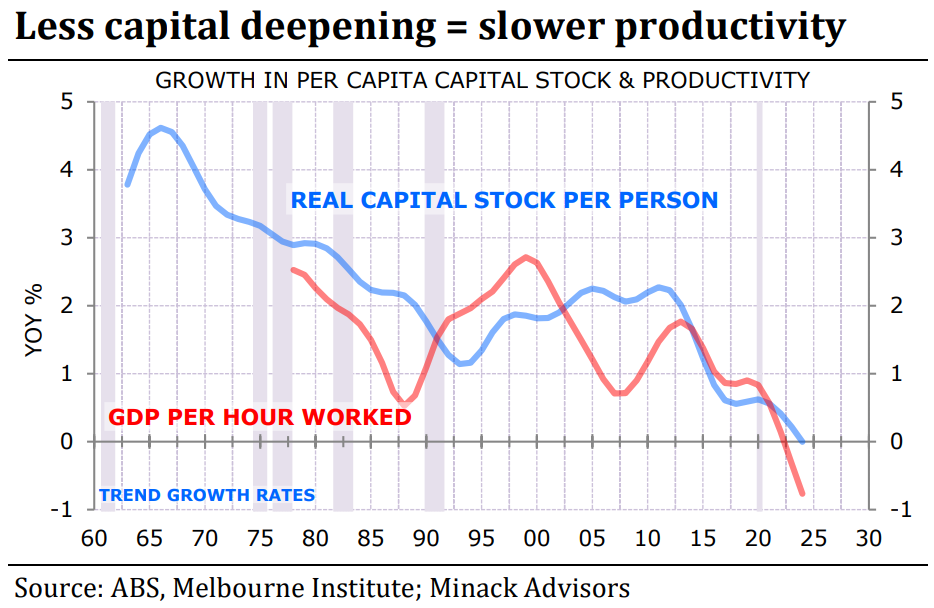

During the ‘productivity loss’ phase, expansion in capital stock (investment in the equipment, tools, and resources required to get the most out of our job) did not keep up with the growth in hours worked.

The PC also notes that many younger and less experienced workers entered the labour sector during this time period. These workers need time to develop the skills and expertise required to match the productivity of their more experienced colleagues.

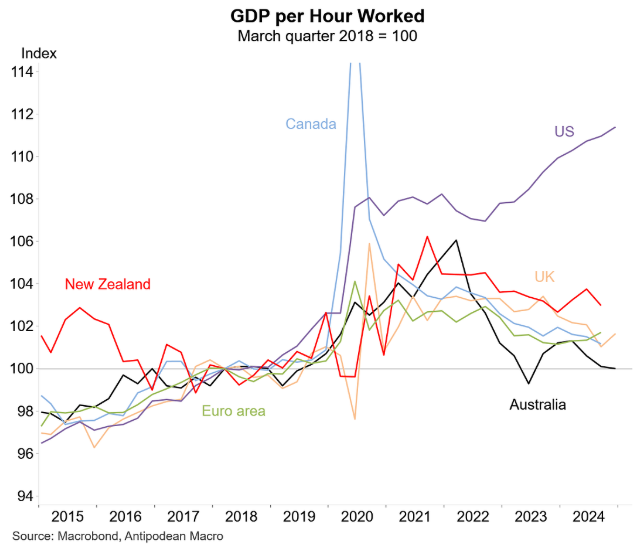

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, the pandemic productivity bubble and bust was a common theme across developed nations:

Even so, Australia’s productivity growth has fallen well below peer nations.

Last month, I presented five reasons why Australia’s productivity growth has declined, namely:

- The mining boom of the 2000s and the associated surge in the Australian dollar contributed to the contraction of Australia’s manufacturing sector.

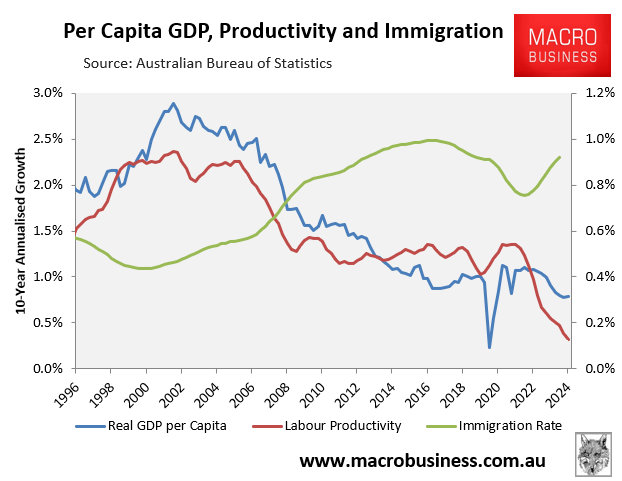

- Capital shallowing, driven by record immigration without a corresponding acceleration in infrastructure and business investment.

- Explosive growth in the non-market economy, facilitated by the expansion of the NDIS.

- Soaring energy costs, driven by gas policy failures and net-zero policies.

- Poor tax policies encouraging housing speculation over productive investment.

Most of my discussion centred on the problem of ‘capital shallowing’ (or the structural decline in capital deepening), which caused the growth in labour productivity and per capita GDP to fall as immigration/population growth rose.

The issue of capital shallowing has gained attention from a wide range of economists, including former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry, former RBA governor Phil Lowe, RBA’s Head of Economic Analysis Michael Plumb, Ross Gittins, Alan Kohler, CBA’s Harry Ottley, and independent economist Gerard Minack, who expertly dissected the issue last year:

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”, argued Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

Indeed, the PC’s latest report gave the following warning about Australia’s poor capital investment and its impacts on long-term productivity:

“While investment and capital has reverted back to its pre-pandemic levels, this is not necessarily a positive story for investment. Investment in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic was characterised by low growth or a decline. If this low rate of investment persists, it may contribute to a longer term productivity slowdown in Australia”.

The outlook for capital deepening remains poor for the simple fact that the federal government plans to grow the population aggressively via net overseas migration, which means that shortages in business and infrastructure investment will persist and the capital-to-labour ratio will fall.

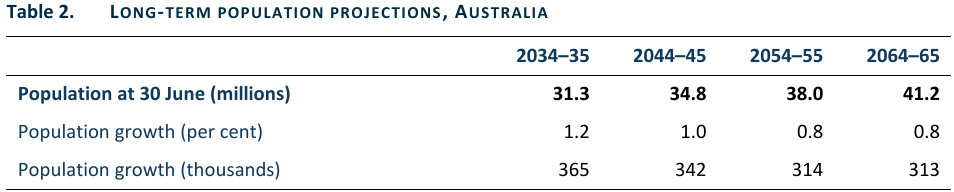

The 2024 Population Statement from the Centre for Population projects that the nation’s population will balloon by 13.5 million in only 40 years:

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

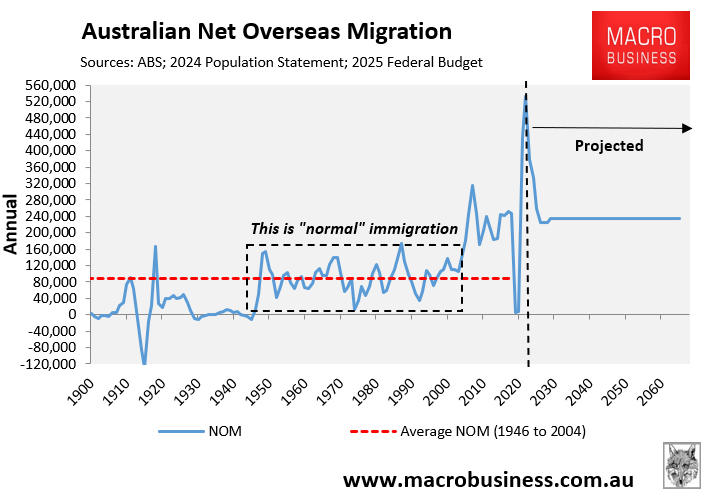

This 13.5 million projected population expansion will be driven by permanently high net overseas migration of 235,000 annually, which is more than double the 90,000 average net migration in the 60 years following World War II.

A 13.5 million population increase is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the nation’s current population in only 40 years.

All of the housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three major cities would need to be replicated in only 40 years to maintain current productivity growth, let alone increase it. That is an impossible task.

Instead, capital shallowing will persist as the population continues to grow faster than the nation’s capital stock.

Having identified the problem of capital shallowing, Australia’s economists should recommend slowing immigration to a level that is compatible with the rate of investment.

Otherwise, Australia’s productivity growth and living standards will remain in the “stagnant status quo”.