Business Council of Australia chief executive Bran Black recently lambasted Peter Dutton’s proposal to cut net overseas migration, claiming it would exacerbate skills shortages.

“It may also compound our existing skill shortages and make it harder to do business”, he said.

Fellow business lobbyists, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Australian Industry Group echoed Black’s claim.

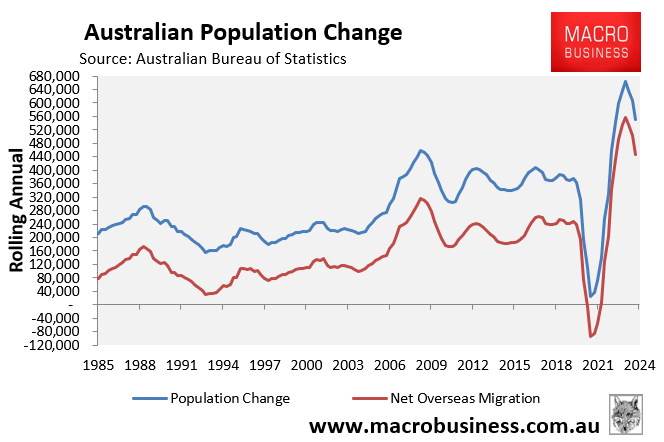

Last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that net overseas migration has slowed from a peak of 555,800 in the year to September 2023 to 445,700 in the year to June 2024.

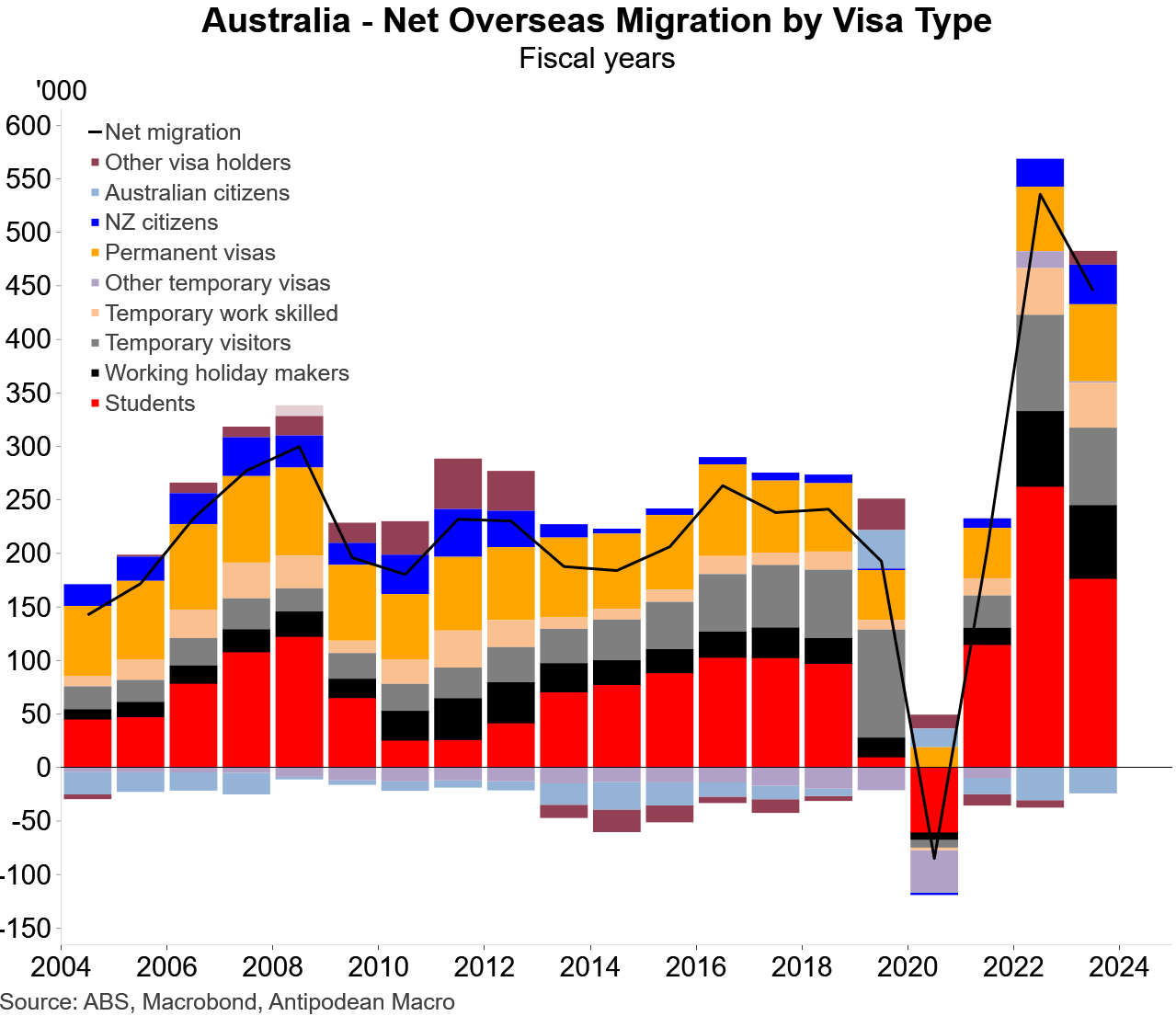

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro, the decline in net overseas migration was caused by fewer international students, which accounted for the smallest share of migration since 2018-19 (excluding COVID-affected 2019-20).

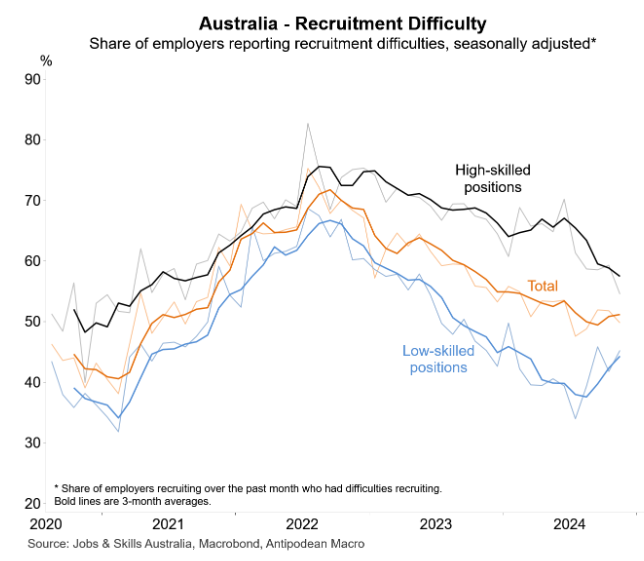

Interestingly, the decline in net overseas migration (mainly students) has been matched with an increase in the recruitment difficulty for low-skilled positions:

Nevertheless, Australia remains relatively oversupplied with low-skilled workers and undersupplied with high-skilled workers.

In fact, despite two years of unprecedented net overseas migration, recruiting highly skilled workers remains far more difficult than before the pandemic.

The reality is that the overwhelming majority of recent migration has been low-skilled. This reflects the surge in international students and working holidaymakers and the fact that most ‘skilled’ migrants work in lower-skilled jobs.

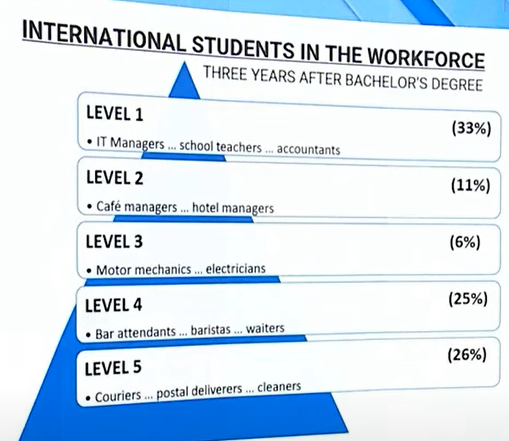

For example, the Migration Review found that 51% of international university graduates with bachelor’s degrees worked in unskilled jobs three years after graduation.

Source: Migration Review (2023)

Given that most graduate visas have a two-year validity period, these individuals will likely be better performers, and the lower-quality international graduates have probably already returned home.

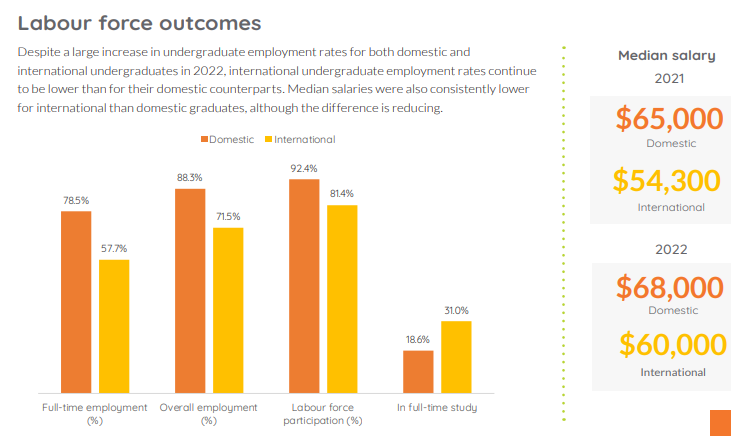

International student graduates also earn significantly less than local-born graduates and have worse labour market outcomes.

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey

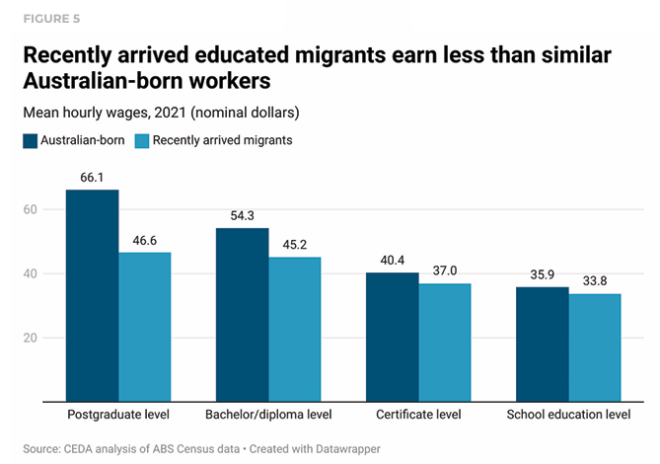

Additionally, CEDA estimates that “skilled” migrants are paid more than 10% less than local workers:

For example, almost 60% of Australian engineers are born overseas, with around half working in low-skilled jobs outside of engineering, such as driving for Uber.

Cover of Engineering Magazine, “Create” in November 2021.

If the business lobby’s “skilled migration” concept includes the above, Australia faces further productivity declines.