CBA’s economics team has assessed the potential impacts of a second Trump presidency and new tariffs on Chinese goods.

They conclude that the tariffs could be disinflationary for Australia in the near term and pose a minimal threat to the nation’s GDP growth.

Key Points:

- The direct impacts on the Australian economy from a second Trump presidency and new tariffs are expected to be limited.

- The US is Australia’s fifth largest export destination.

- The larger impact is likely to be second-round impacts from any slowdown in China’s economy, Australia’s largest trading partner. But we expect the Chinese government to step up budget support to mitigate a material slowdown.

- A flexible exchange rate, an independent central bank, and fiscal policy can mitigate impacts on Australia from US tariffs.

Overview:

Since President Trump was re-elected over two weeks ago, financial markets and economists have been analysing the potential impacts on the world economy, China’s economy and the Australian economy.

Generally, three impacts are expected: larger US budget deficits, higher US inflation and more volatile economic growth. The US dollar should be stronger and US interest rates should settle higher.

But the impact on each variable and the overall economy is uncertain as the RBA Governor (and the Federal Reserve Chair) have both highlighted in recent comments.

China, and Europe to a lesser degree, are in President-elect Trump’s sights as he attempts to boost domestic output and reduce imports from China and Europe. The binary impacts from the imposition of trade tariffs are better understood on each economy.

Australia should be relatively immune from direct impacts from an increase in tariffs in the US. The larger impact is likely to come through second-round impacts to China’s economy and reduction in demand for Australia’s key exports.

However, policy does not operate in a vacuum. The impact will be dependent on how other countries react to the imposition of tariffs and any offsetting policies implemented through monetary and fiscal policy. Currencies also provide a buffer.

These responses create additional uncertainty of the impact. Uncertainty for financial markets, economies and consumers have lifted and will remain elevated in the next few years. Uncertainty can have an economic consequence too and can lead to heightened volatility in financial markets.

Our InternationalEconomics colleagues have written on this topic. They have modestly downgraded global growth with impacts felt in China and Europe. A still healthy 2.9% in expected in 2025 and 2026.

In the rest of this note, we dive into Australia’s trade relationship with the US, how second-round impacts from China could impact Australia, and other related issues.

A refresher on Australia’s trade with the US

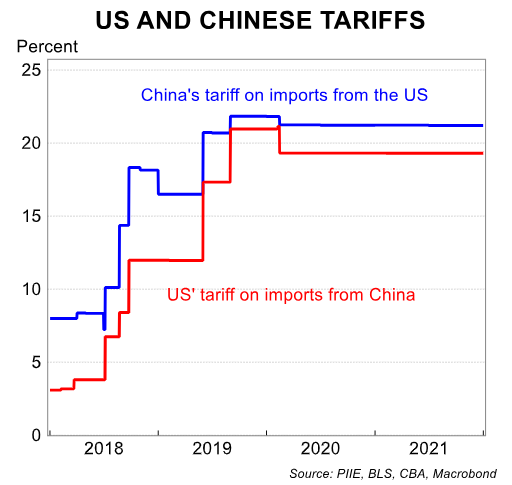

President Trump-elect campaigned on introducing tariffs of up to 60% on imports from China and between 10%-20% on all other imports. As a reminder, President Trump implemented tariffs in his first term (which remain in place, chart 1).

The Chinese government retaliated by increasing tariffs on imports from the US. There remains uncertainty over the size, timing and the duration of the proposed new tariffs.

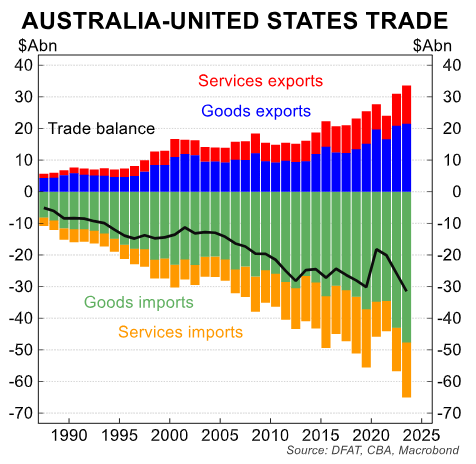

Australia runs a large trade deficit with the US, ie Australia imports more than it exports to the US (chart 2). Australia also has a free trade agreement (FTA) with the US. Currently around 97% of our exports to the US are tariff free.

The imposition of tariffs on Australian imports will impact on our export sector. However,there is uncertainty if Australia will be exempt (our steel exports were exempt last time) and what imports from Australia may be targeted.

It will take some time to renegotiate the FTA with the US. In addition, we consider the US government will prioritise negotiations with economies that run a trade surplus with the US.

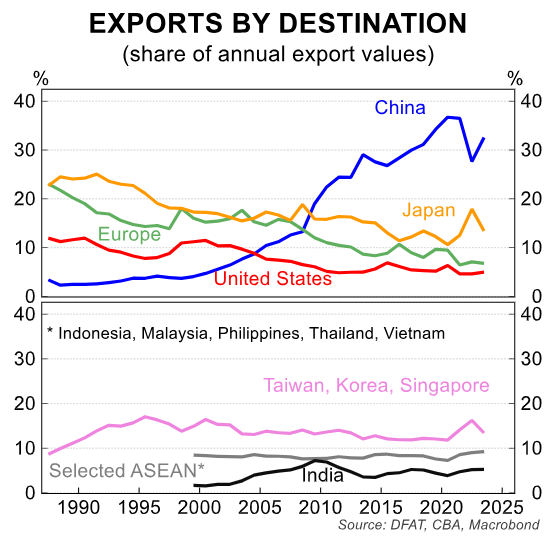

In 2023, the US was Australia’s 5th largest export partner at a value of $A33.6bn, a relatively small 5% share of exports. In comparison, China was the largest at $A219.0bn, which accounts for 33% of Australia’s total exports.

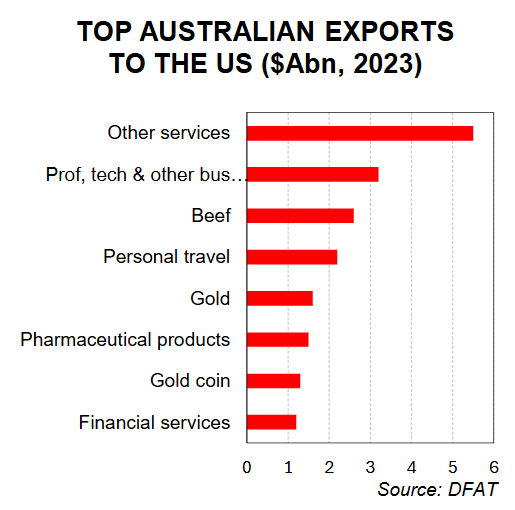

Australia exports a range of goods and services to the US (chart 3). The largest two exports are ‘other services’ and ‘professional, technology and other business services’. Tourism (ie tourists from the US holidaying in Australia) is the fourth largest export. Generally the level of the Australian dollar will influence tourism demand. The Australian dollar has fallen against the US dollar which makes it cheaper for US travellers to Australia.

Tariffs are generally imposed on goods imports by customs authorities. Therefore, Australian services exports are unlikely to be impacted by trade restrictions.

Beef is the largest goods export to the US. In 2023 Australia exported $A2.6bn of beef to the US. Exports in the first nine months of 2024 have already exceeded 2023 levels. The US cattle herd is at the lowest level since the 1950 sand US beef imports have been rising. Any tariff on beef imports would lift prices for US consumers.

For context, Australia’s beef exports to the US are 25% of total Australian beef exports in 2024 to date. US beef imports from Australia have been 19% of total beef imports in 2024. In other words, the beef trade is important to both economies.

Other key exports to the US include pharmaceutical products, medical instruments, aircraft and parts. Gold and gold coins are the other large export.

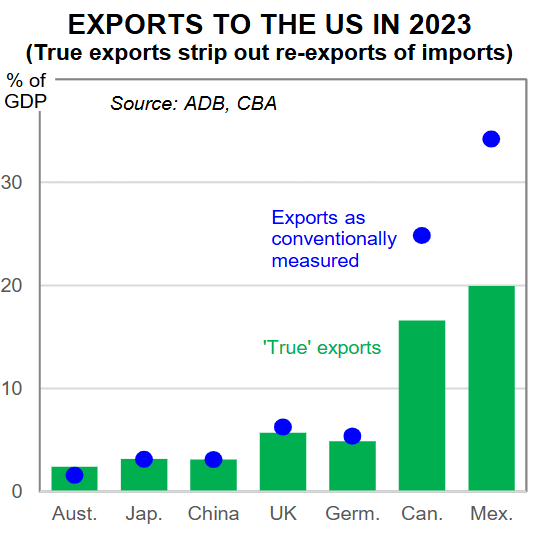

Australia has a small direct export exposure to the US (blue dots in chart 5) compared to other major economies.

We judge the impact on Australian exports from the possible imposition of US tariffs would not materially impact the Australian economy. The impact on specific industries could be material, however. The 2020-24 period of trade tensions between China and Australia did divert trade.

The last of tariffs on Australian goods (wine) were lifted in March 2024. The domestic take up of goods is possible if Chinese demand decreases.

Overall, we expect a modest direct impact on the Australian economy on a blanket imposition of tariffs on all exports to the US. We expect exemptions on at least some exports to mitigate the impact further.

Indirect impact from a slowdown in China

The potentially larger impact would come through the second round or indirect effects stemming from atrade-induced slowdown in China.

Again, there is a large degree of uncertainty given the potential timing, size and duration of higher tariffs.

Australia’s ties to China

Since the rise of China in the 2000s, there has been a direct link between the Chinese and Australian economies. A slowdown in China would slow the Australian economy, all else equal,through lower export income and possibly lower investment.

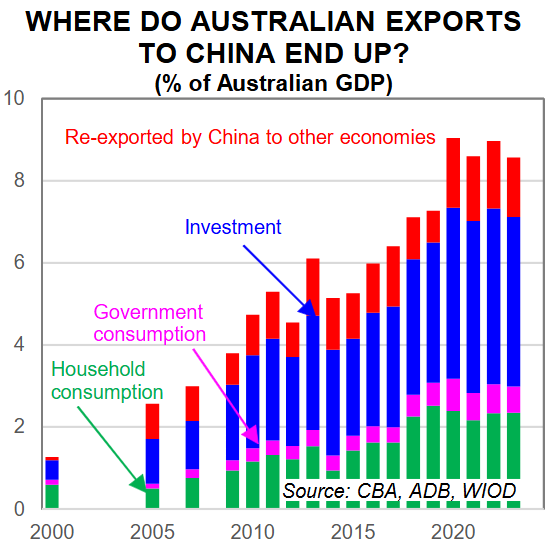

About one-fifth of Australia’s exports to China are re-exported to other countries (red bars in chart 6). However, most of Australia’s exports to China satisfy Chinese investment and consumption.

We estimate around 7% of Australian GDP satisfies Chinese domestic demand (blue, pink and green bars in chart 6).

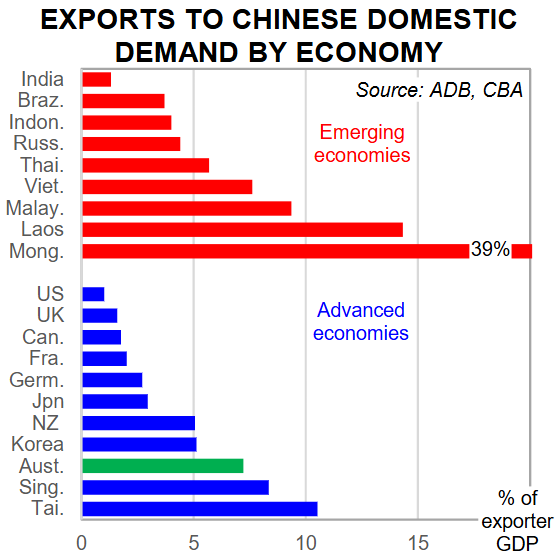

By comparison, the Australian retail industry accounts for only 4% of Australian GDP.Among advanced economies, Australia has a high exposure to Chinese domestic demand (chart 7).

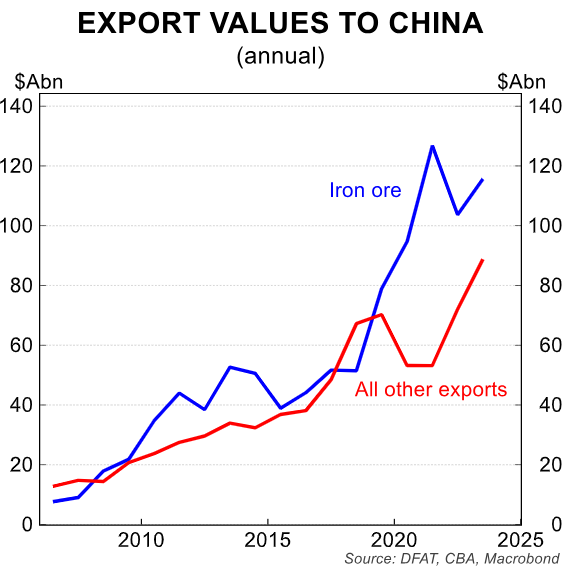

In 2023, China accounted for 32.6% of Australia’s export values. The key resource in the China-Australia trading relationship is iron ore. In 2023, Australia exported A$116bn of iron ore to China, compared to A$89bn of everything else, highlighting just how important the commodity is (chart 8).

How could a slowdown impact Australia?

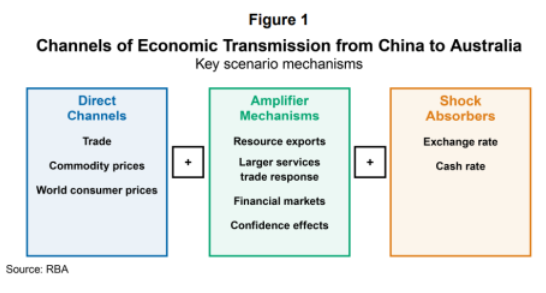

A framework for thinking about how a slowdown in China would impact on Australia was outlined in a 2019 RBA Bulletin article (see chart 9). We lean on this research to guide our thinking on the spillovers from a trade-war induced slowdown in China to Australia.

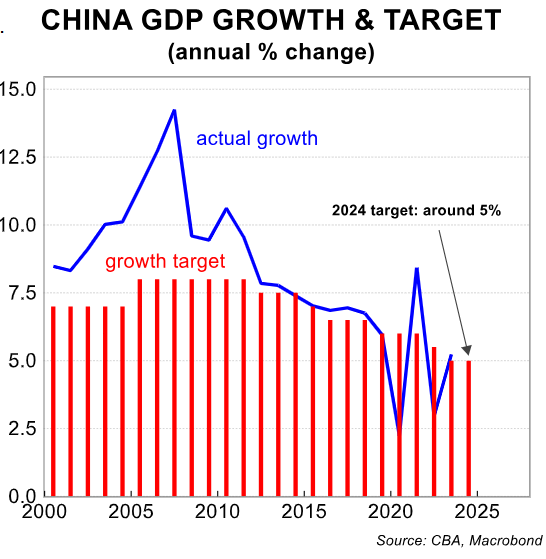

A 60% US tariff on all imports from China, all else equal, would lead to a slowdown in China’s economy growth. As a reminder, economic growth in China has already underwhelmed in 2024. Most economists expect China will miss its 5% economic growth target (chart 10).

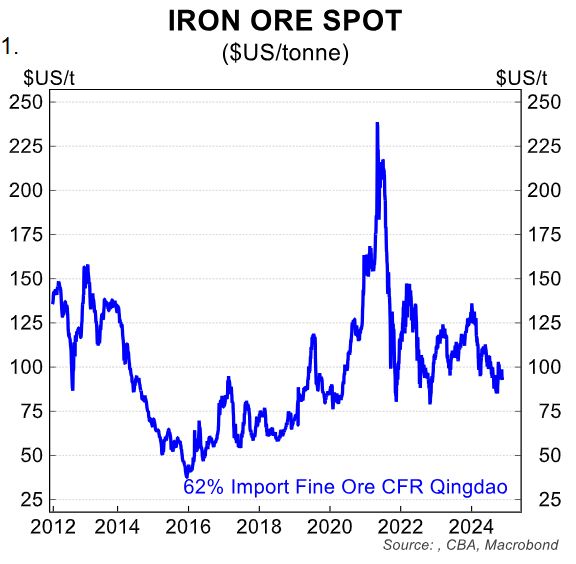

A slowdown in China would also likely have a negative effect on commodity prices because of China’s outsized influence on commodity markets. Lower commodity prices would arguably have the most direct link to Australia.

A fall in commodity prices, particularly iron ore, would lower Australia’s terms of trade and lead to less export income.government revenue and corporate profits. Our International Economics team expects the Chinese government to increase government spending in 2025 in response to its soft economy.

A recent clean-up of local government debt would make any focus on the property and infrastructure sector more potent. Chinese policymakers may also be waiting for clearer signals of tariffs from the second Trump administration before responding with additional stimulus.

Iron ore and base metal prices have increased and decreased in line with market speculation of Chinese government stimulus over the next 6 months. There is speculation China is pulling forward exports of steel to get ahead of rising global trade tensions. President elect Trump is inaugurated on 20 January 2025.

China’s steel product exports surged in October to the highest level since September 2015. Notably, the surge in steel exports in October was before the US election result was known.

The Federal budget is exposed to a fall in commodity prices from mining profits and royalties. Based on Treasury’s sensitivity analysis, a fall in the iron ore price of $US10/tonne would decrease the tax take $A3.4bn over the four years from FY24 and detract ~$A25bn from nominal GDP.

A more significant fall of $US30/tonne would reduce the tax take by $A10.2bn and reduce nominal GDP by A$74.7bn (0.6% of GDP over the period).

It is worth noting however that the Federal Government’s iron ore forecasts are chronically conservative. The Federal budget assumes iron ore prices will fall to $US60/t (62% Fe, FOB Australia, equivalent to ~$US70/t 62% Fe, CFR China).

The current spot price is around $US100/t (chart 11). Therefore, a drop in the price of $US30/t would bring it closer to the Budget forecast. As such, the Budget would not get the ‘surprise’ upward revision to revenues but rather possible downgrades.

But our Commodities strategist Vivek Dhar believes there is a low probability of large falls in the iron ore price below $US100/t.

For context, BHP estimates that 130-140 Mt or 8-9% of seaborne iron ore supply will need to exit to sustainably justify $US90/t. Export volumes from Australia to China would likely soften in the event of a material Chinese economic slowdown.

Resources exports make up the majority of Australian exports to China. If China reduces spending and investment on infrastructure, there will be less demand for Australian commodities. The magnitude of the fall may be limited due to Australian commodities being high quality and low cost.

In other words, other producers would likely feel reduced demandbefore Australia. However, because ~70% of China’s iron ore imports come from Australia, a reduction in Chinese import volumes would reduce Australian export volumes, a negative for economic growth.

Resource export values would fall considerably in the event of a Chinese slowdown. Private Australian investment and consumption could also soften in response to lower export income.

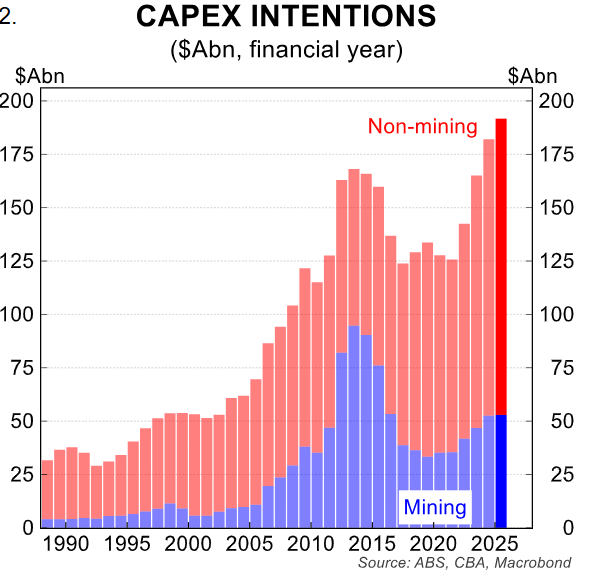

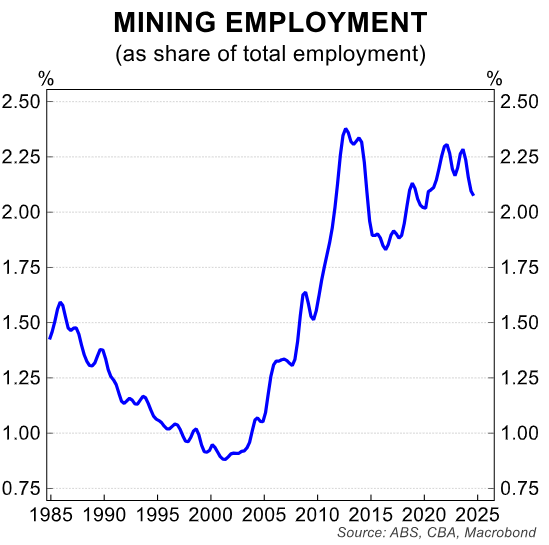

If uncertainty rises and confidence is dim on the outlook for commodities, miners are less likely to invest to expand or maintain production. Mining investment is set to plateau this financial year after several years of gains (chart 12).

Mining employment comprises only 2% of employment (chart 13). Service exports are also exposed to a slowdown in the Chinese economy with less travel and education trade possible.

This may be somewhat cushioned, however, by the fact that the level of Australian services exports to China are still well below the pre-covid peak and so may still recover further (chart 14).

Offsetting factors

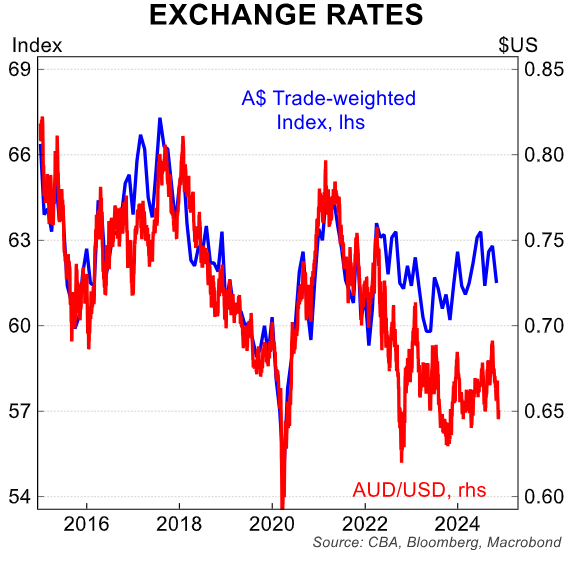

There are several mitigating factors that could limit the impact on the Australian economy. The first is the flexible exchange rate.

The Australian dollar has already depreciated. A lower Australian dollar helpsto protect Australian export businesses. The fall in the Australian dollar has been smaller than after President Trump’s first win in 2016.

However, the decline in the Australian dollar has been larger against the USD compared to the Trade Weighted Index (TWI) (chart 15). We expect the main impact on Australia would be through lower national income if there is a material slowdown in China.

A negative demand shock to Australia could also be met by monetary policy easing from the RBA. Interest rates are already at restrictive levels. We also expect the Chinese authorities will ramp up stimulus to support their economy in the event of a trade conflict.

Our International Economics team have revised slightly lower its GDP projections for China, which will again mitigate the impact on Australia. They expect growth of 4.7% in 2024, 4.9% in 2025 and 4.6% in 2026.

The external sector will become less supportive of the Chinese economy from next year. Our International Economics colleagues expecta ‘forceful’ stimulus response, including more fiscal and monetary stimulus.

Policymakers have recently hinted at an increase in the budget deficit, and greater support for consumption and the property sector. A focus on households would have a lower positive impact on the Australian economy compared to previous episodes that focused on construction. But the positive impact on Australia would not be zero.

Chinese stimulus therefore looms as an option that is enacted if China’s economy is impacted too adversely by a trade conflictwith the US. Ironically, the more punitive President Trump’s policies against China, the more the market will price in Chinese stimulus and look through any current downturn in China’s economy.

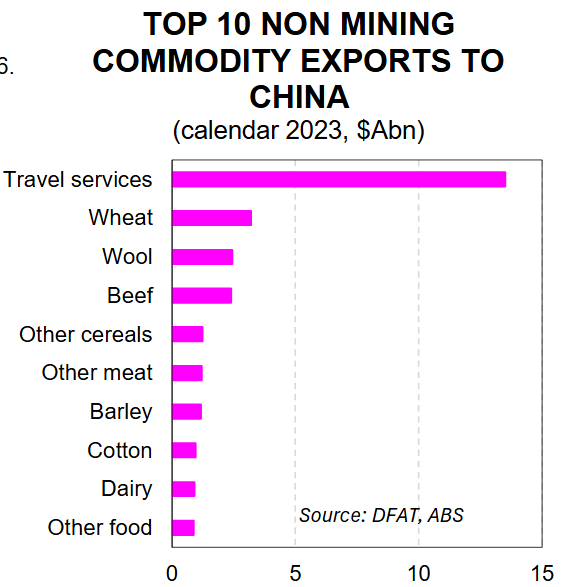

Australia’s exports to China are dominated by mining and energy commodities: iron ore, gas, coal, gold and other minerals. But Australia also exports services (mainly education and travel) and agricultural goods including wheat, wool, beef and cereals that could benefit from a consumption focussed stimulus package (chart 16).

Given this, and the Australian economy’s ‘shock-absorbers’ of a flexible exchange and interest rates, as well as a likely response from Chinese authorities, we consider a material downturn in Australia is unlikely but it is a headwind to take note of.

Our assessment of the impact may change once details of tariffs and responses emerge. If the trade policies are enacted broadly as announced, we would expect GDP growth in Australia to be modestly lower than otherwise, albeit the size is dependent on China’s growth and budget support.

Slower Australian economic growth also implies the unemployment rate will be higher than otherwise. The Peterson Institute estimates that in the scenario of a 60% tariff on China with retaliation, real GDP growth in Australia would be 0.1ppt less in both 2025 and 2026.

This is a useful guide, but the amount of uncertainty around how these policies will unfold, and how other countries will respond make point estimates extremely difficult at this stage.

The impact on inflation will depend on the level of retaliation to US trade barriers from other countries. There is a probable scenario in which consumer prices in Australia are lower in the near term due to goods imports from China becoming cheaper as producers attempt to mitigate the tariff impact and lose the US as a potential export destination. Australian consumers benefit as a result.

Longer term, higher trade-barriers globally will put upward pressure on inflation and would see interest rates settle higher compared to otherwise. But such an outcome would need to involve something comparable to a global trade war, which we do not consider likely.