I noted last week how Australia’s Albanese government seems to have copied Canada’s Trudeau government on housing and immigration.

In 2022, Canada’s then-immigration minister, Sean Fraser, viewed immigration as a competition for global talent that he was determined to win.

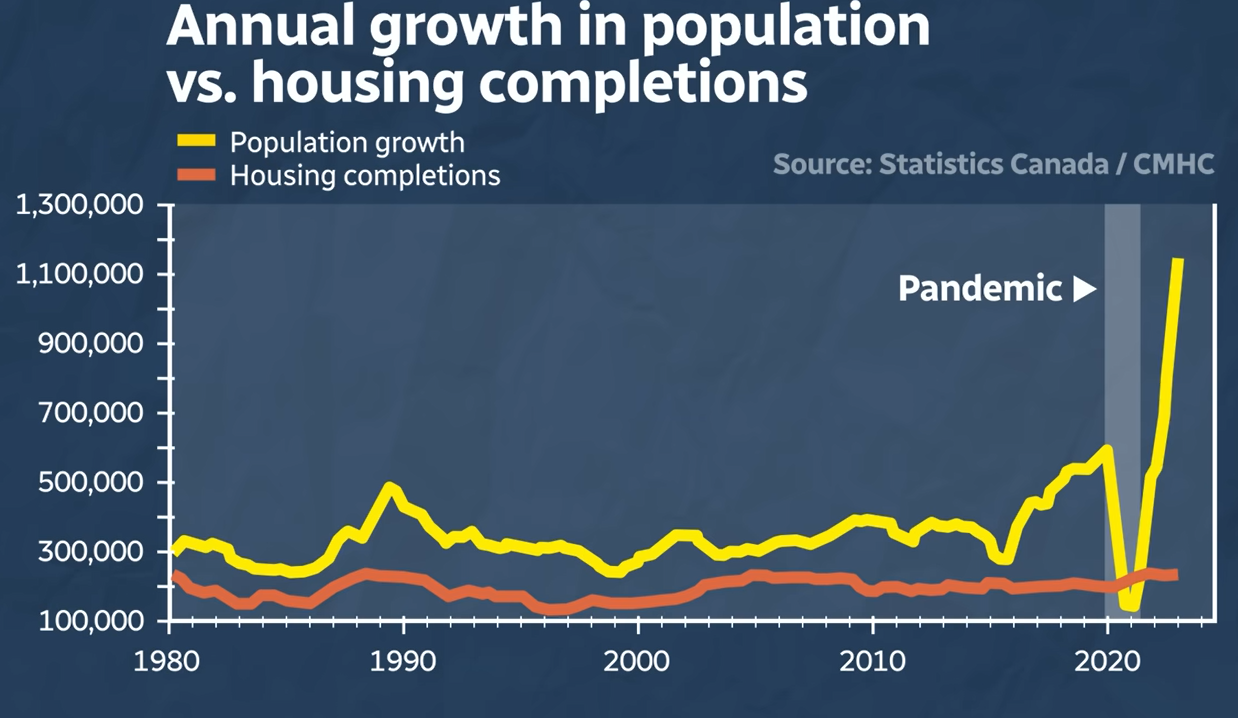

Canada has just experienced a record population increase of approximately 800,000. Despite this, Fraser declared that Canada would accept 465,000 permanent residents in 2023, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025.

Canada’s population then exploded by more than 1.2 million last year, causing an unparalleled housing shortage.

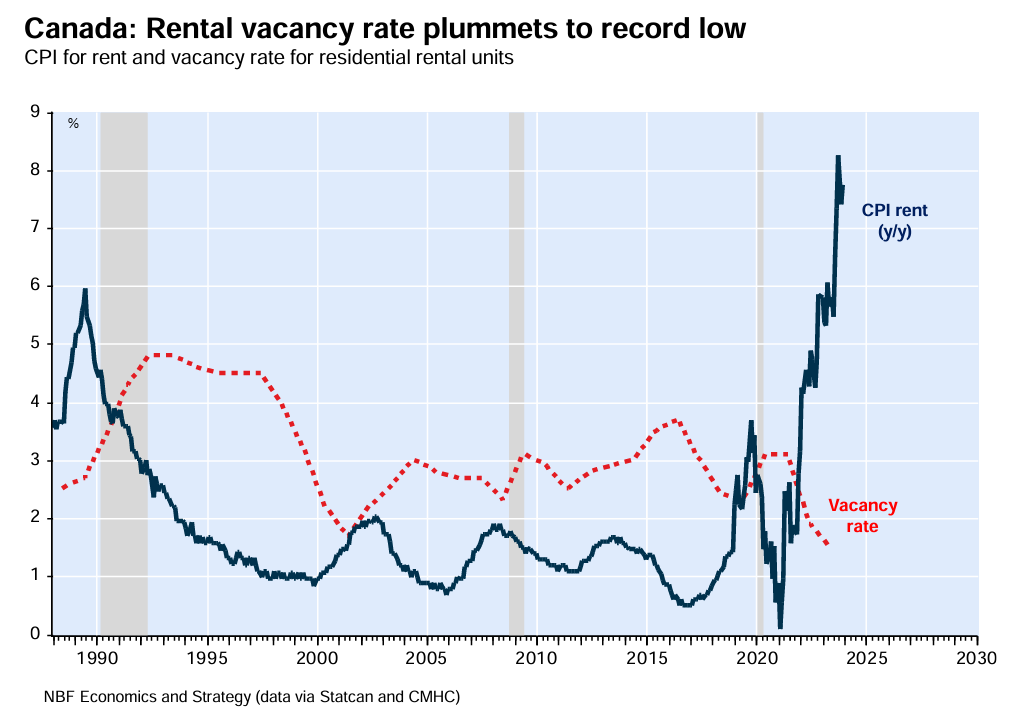

This enormous disparity between population demand and supply drove rental vacancy rates to all-time lows and rental inflation to record highs.

Despite creating Canada’s housing crisis via unsustainable immigration levels, slick-talking Sean Fraser was appointed housing minister in July 2023.

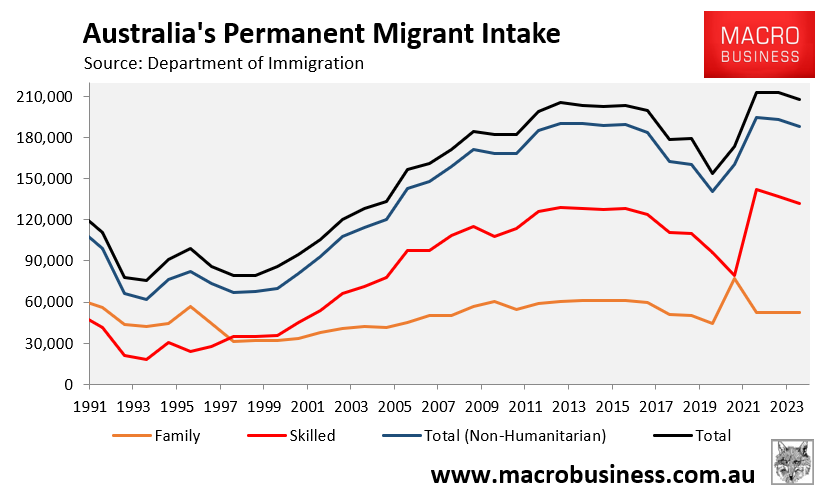

Australia has charted a similar course.

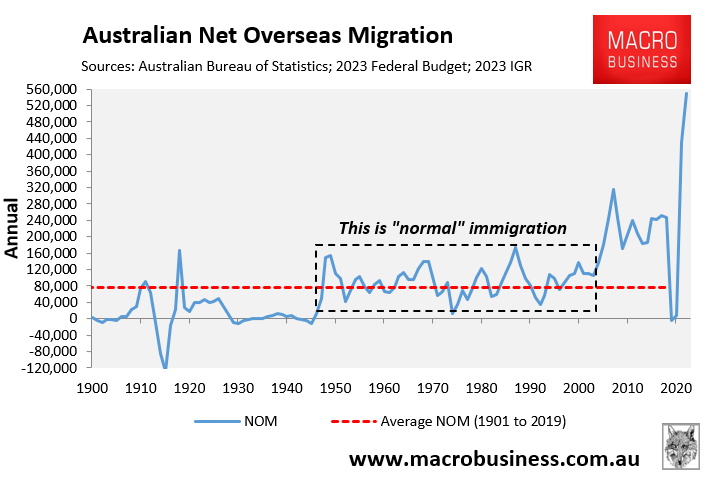

In 2022 and 2023, then-Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil promised to increase immigration, citing skills shortages and a “race for global talent”.

O’Neil argued that immigration had been the “special sauce in our national story” and advocated for more.

She stated that Australia needed to transition “away from a system which is almost entirely focused on how we keep people out to one that recognises that we are in a global war for talent”.

Australia then experienced the largest increase in net overseas migration in its history.

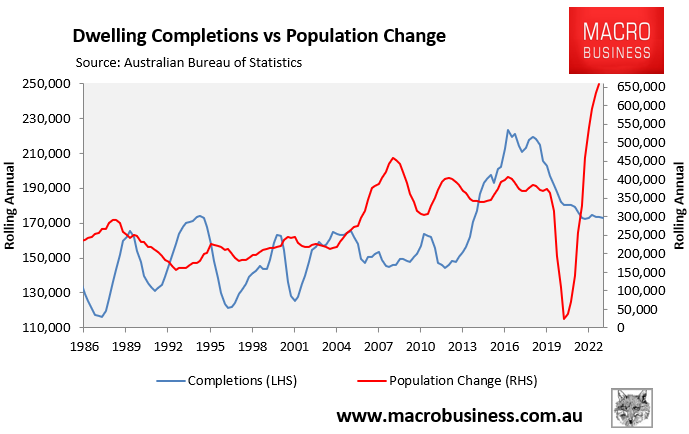

A considerable imbalance emerged between population demand and housing supply.

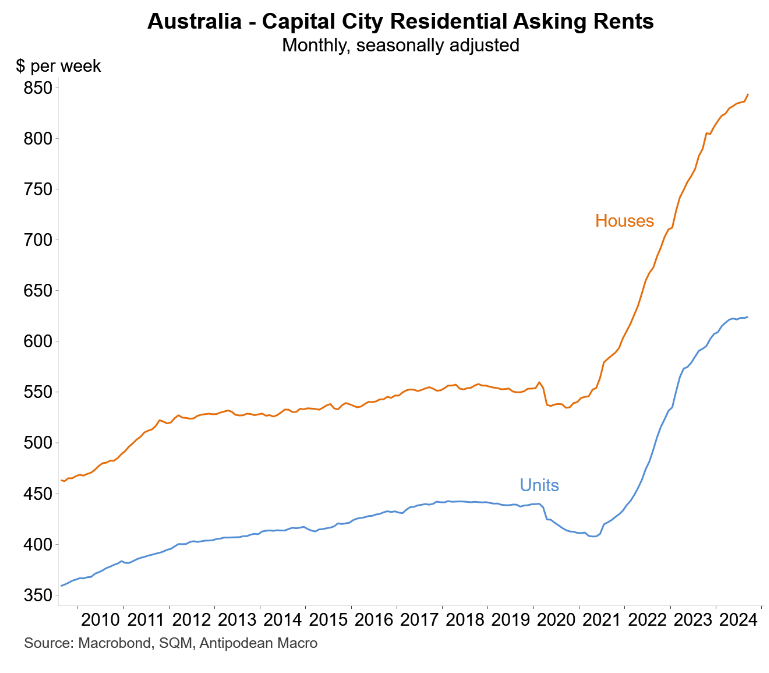

Rental vacancy rates plummeted to historical lows while asking rents surged.

After causing the rental crisis through reckless levels of immigration, slick-talking Clare O’Neil was appointed housing minister in August 2024.

It was almost as if Australia’s Albanese government had taken its cues from Canada’s Trudeau government.

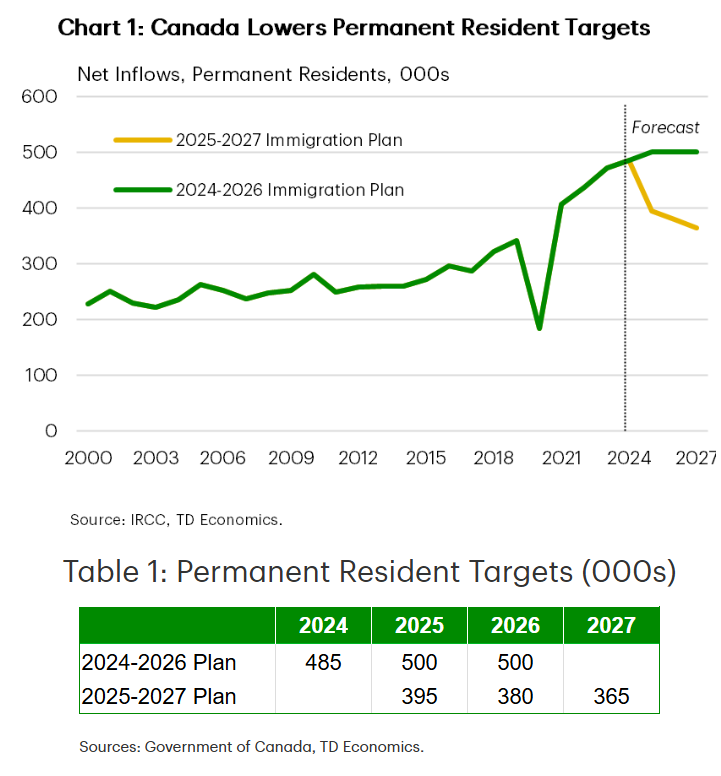

Amid the deepening backlash against excessive levels of immigration, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pulled a 180-degree pivot and vowed to pause Canada’s immigration for two years.

Under the plan, Canada will lower the permanent migrant intake over three years.

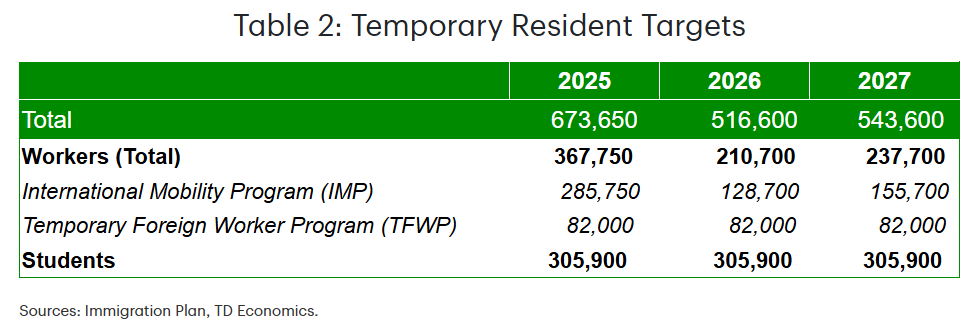

Canada will also lower the number of temporary residents in the country:

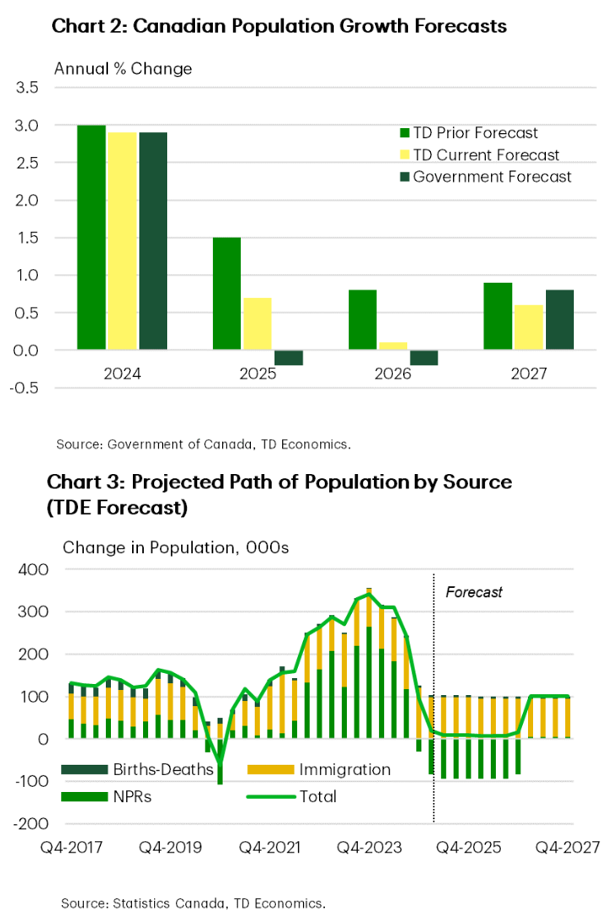

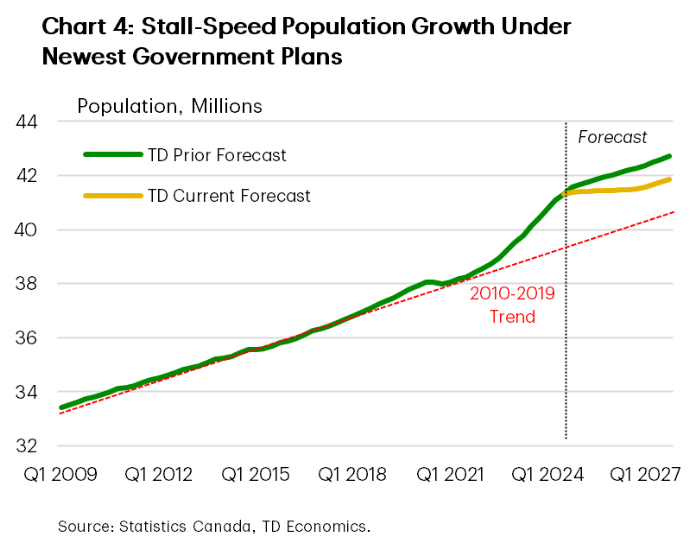

As a result, Canada’s population will stabilise for two years before growing more slowly thereafter.

The federal government’s projections show modestly negative population growth (-0.2%) over the next two years before flipping back to positive territory in 2027 (0.8%).

However, Canada’s population will remain significantly larger than its 2010-2019 trend:

Trudeau claims that the pause in population will “give our economy and our communities the chance to catch up, with things like our plan to build millions more homes”. It will also “see more corporations investing in Canadian workers and youth rather than relying on cheap foreign labour” and bring “rental prices down in big cities”.

Canadian Bank TD also noted that the immigration cut would “lower rent inflation, better incentives for businesses to invest, and potential for a faster normalization in policy rates. These reforms mark a shift back in the right direction”.

The Australian Albanese government should emulate Canada by cutting the permanent migrant intake via:

- Eliminating parental visas (as the Productivity Commission suggested) would reduce the family stream’s allocation by about 8,000 permanent places.

- Cutting permanent skilled visa places from 132,100 places currently to 95,000. This could be accompanied by an increase in the minimum salary threshold to a genuinely skilled level to improve quality.

The Australian government could also cut humanitarian visa places back to their old level of 13,700 from 20,000 currently.

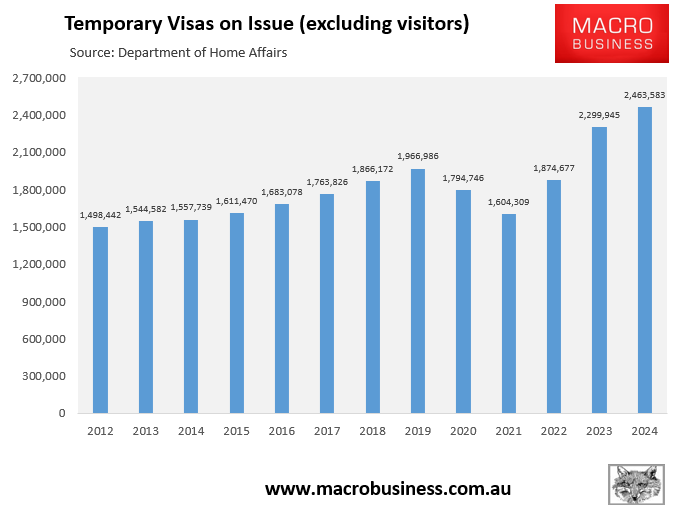

The stock of temporary migrants in Australia has also grown to absurd levels and should be cut.

First, the temporary skilled visa salary threshold should be lifted above the median full-time salary. Doing so would reduce the flow of skilled temporary migrants and improve quality.

Second, the Australian government should reduce the flow of student visas via:

- Significantly tightening English-language standards and requiring prospective students to complete entrance examinations before being permitted to study in Australia.

- Significantly increasing financial requirements, with funds paid into an escrow account before arriving in Australia.

- Reducing the number of hours that international students are allowed to work and severing the direct link between study, work, and permanent residency.

- Only allowing top-of-class graduates to receive a graduate visa.

- Given that Australian universities are non-profit entities that currently do not pay taxes, imposing a levy on international students to ensure that Australians receive a financial cut from the trade.

Third, access to bridging visas should be tightened and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal should be bolstered to prevent migrants from staying in Australia when their primary visa expires.

These sorts of reforms would cut overall migration numbers and raise quality.

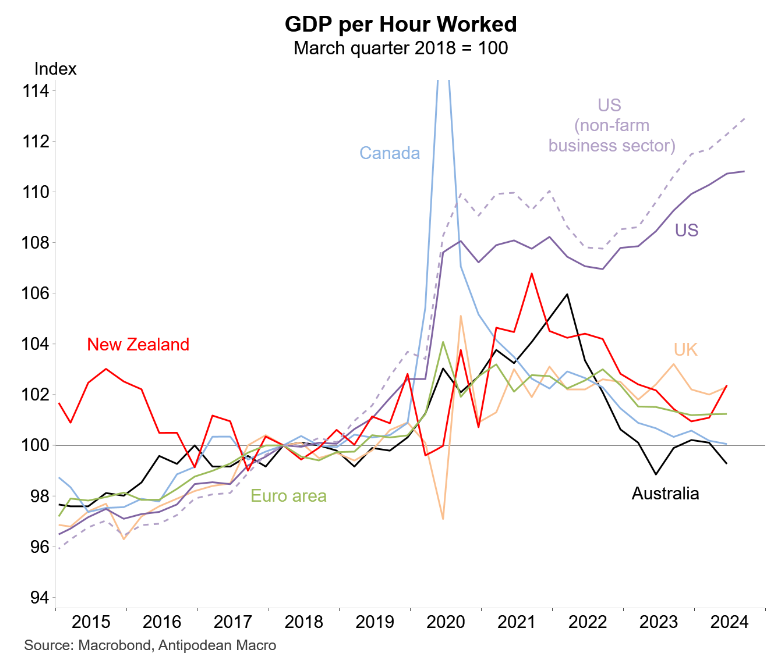

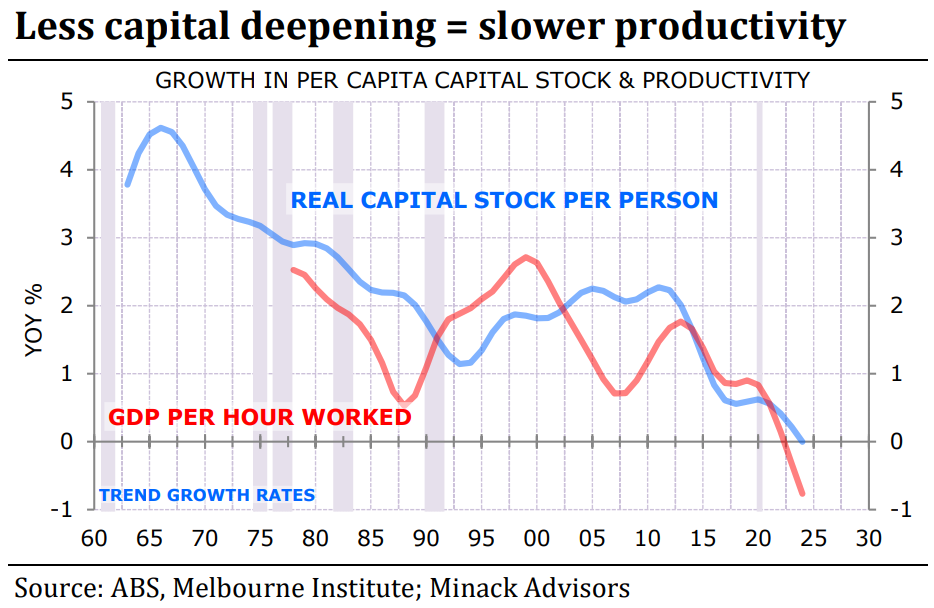

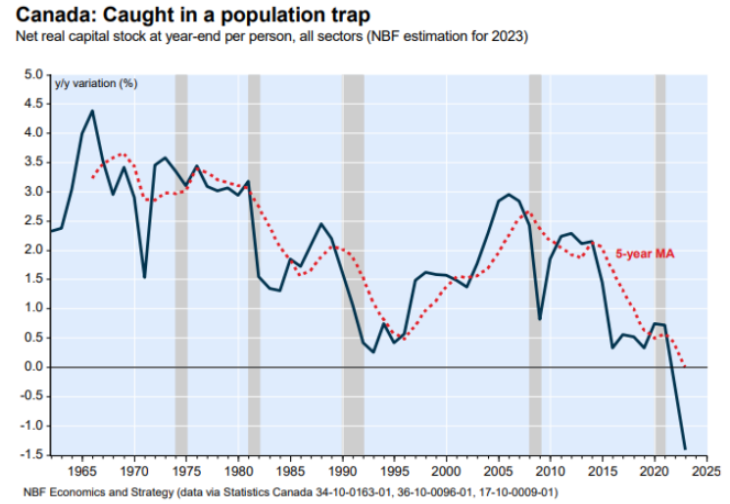

Years of excessive levels of immigration have left both nations with housing crises that will take years to repair (if ever), stagnant productivity, and declining living standards.

Both nations have suffered from chronic “capital shallowing” because population growth via high immigration levels has exceeded business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

Australian capital shallowing

Canadian capital shallowing

Both countries jumped the shark on immigration and need a prolonged pause, followed by a lower sustainable immigration rate in the future.