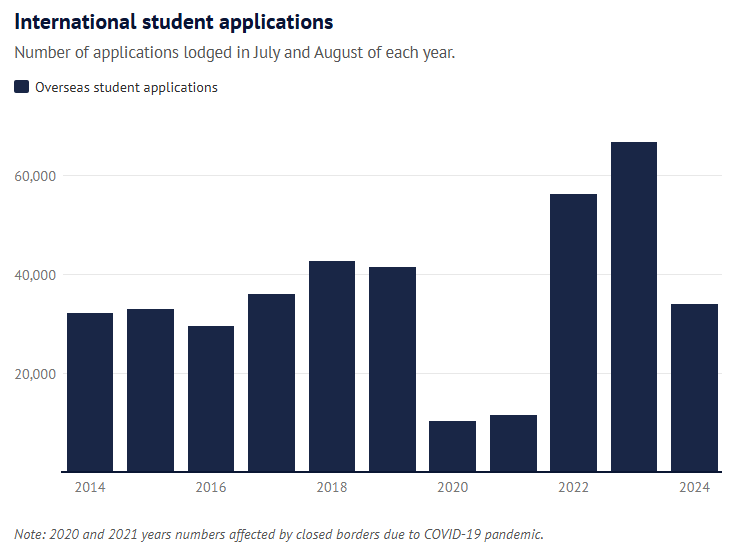

Preliminary data reported in The SMH shows that the number of offshore student visa applications fell to 18,697 in July, compared with 36,207 during the same period in 2023.

The downturn continued in August, with applications falling from 30,703 a year earlier to just 15,270.

The sharp fall coincided with the federal government’s push to rein in the number of international students in Australia via measures such as doubling the student visa application fee and capping international student numbers.

Applications from students in India, the second-largest source country for overseas education, were down 66%.

The number of Indian students applying declined by over 8000, from 13,047 visa applications in July and August of last year to 4,383 this year.

Nepali applicants also fell from 4672 to 1944, and Vietnamese applicants fell from 2617 to 1074.

Applications from students in the Philippines and Pakistan have almost completely dried up: Filipino applications have tanked from 5,126 to 849, while Pakistani applications fell from 4234 to 616.

Chinese applications, on the other hand, were much more consistent, with 12,012 filed in July and August of this year, 1100 fewer than the same period the previous year.

Professor Andrew Norton from ANU commented that applications have fallen due to “a mix of very low success rates, the visa fee has more than doubled, the English language requirement has increased, as has the amount of money they need to show they have”.

“The Indian market is very sensitive to migration policy and costs, so we’re seeing them way down. The Chinese market is less sensitive to those issues so it’s been reasonably resilient”.

Visa applications for vocational education and training have also plummeted from 10,916 to 2239, reflecting the crackdown on shonky private colleges.

As usual, Universities Australia chief executive Luke Sheehy is crying poor, claiming that having fewer non-genuine students from poor nations has cost the economy $4 billion so far.

“This is what happens when international students are told to stay home, which is effectively what the government has been saying”, he said.

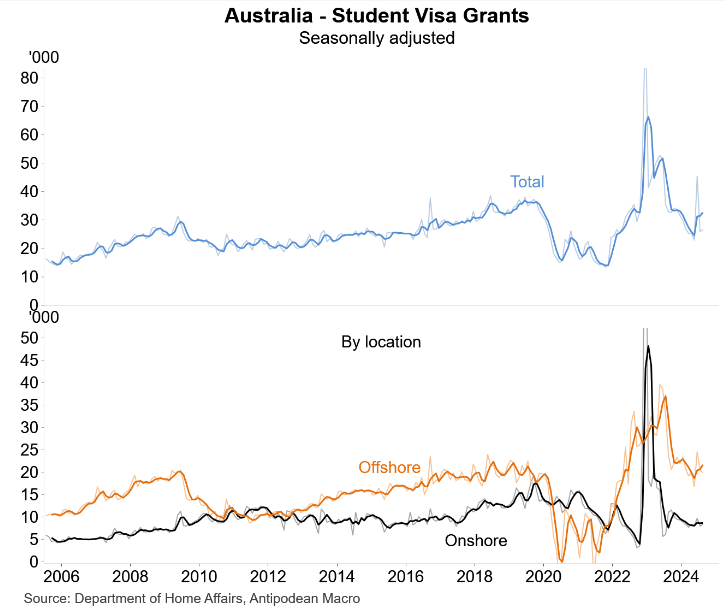

The reality of the situation is that while the number of applications may be down, the number of offshore visas granted has merely returned to pre-pandemic levels:

However, the average quality of students would also have increased, with fewer coming to Australia purely for work and residency.

This is exactly what the government should aim for: a much lower quantity of higher-quality students.

The federal government should tighten the clamp further via:

- imposing stricter English-language requirements and requiring prospective students to pass entrance exams;

- increasing financial requirements, with funds deposited into an escrow account; and

- removing the link between study, work, and permanent residency.

Reforms of this nature would dramatically increase the quality of students, would transform education into a genuine export industry, would boost the quality of graduates (and productivity), and would lower net overseas migration and ergo pressures on housing and infrastructure.

International education must be transformed into an industry centred on quality rather than volume.