Canada’s economy is a basket case.

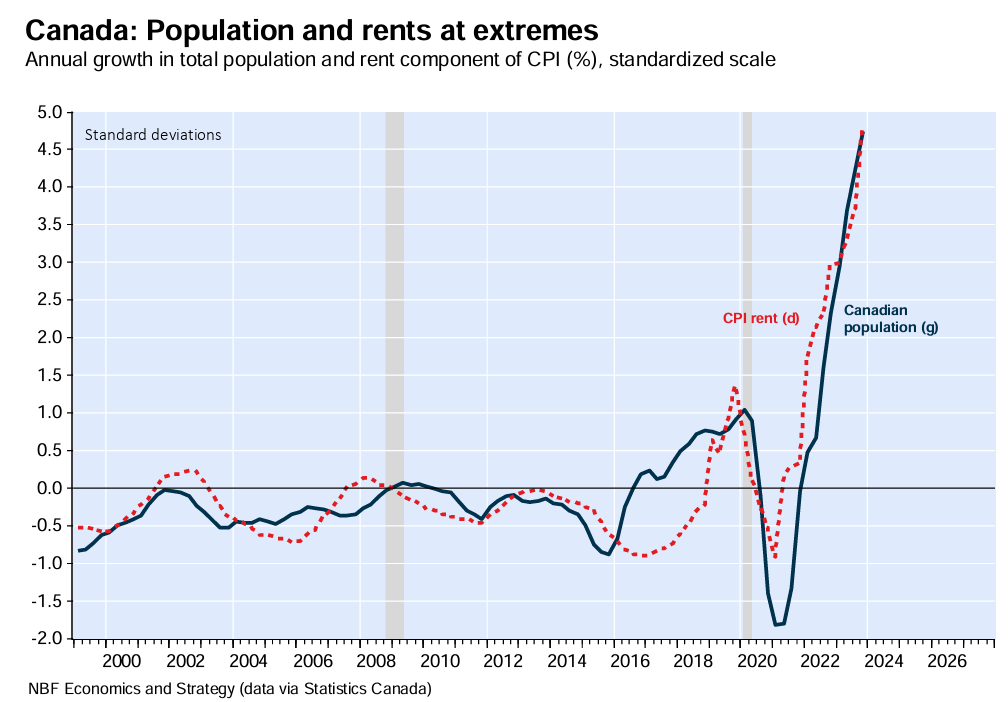

The biggest migration surge in history has left Canadians with the worst rental crisis in living memory:

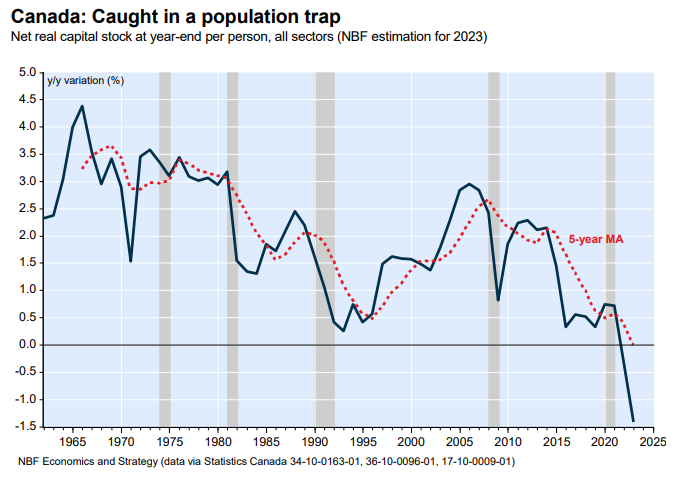

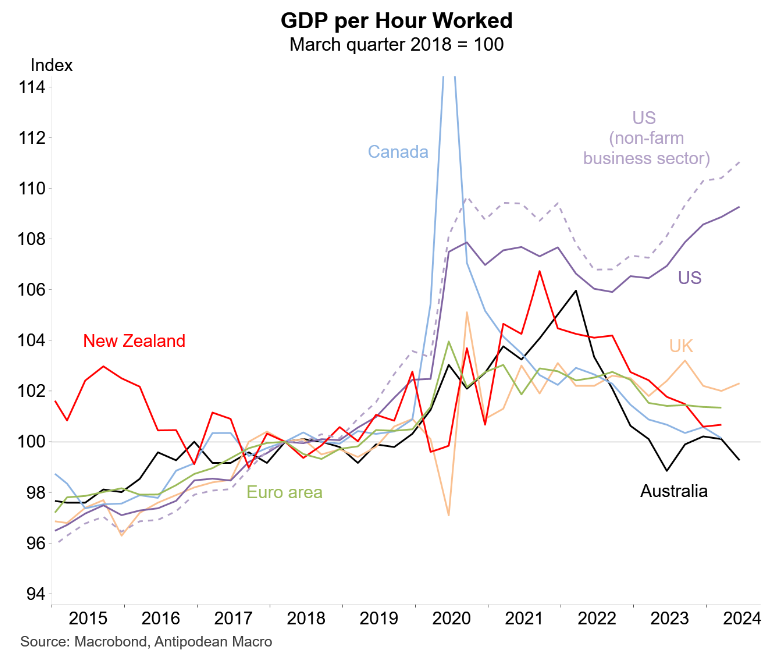

Canada’s productivity growth is also deplorable, driven to a large extent by “capital shallowing” as the rate of population growth has outrun business and infrastructure investment:

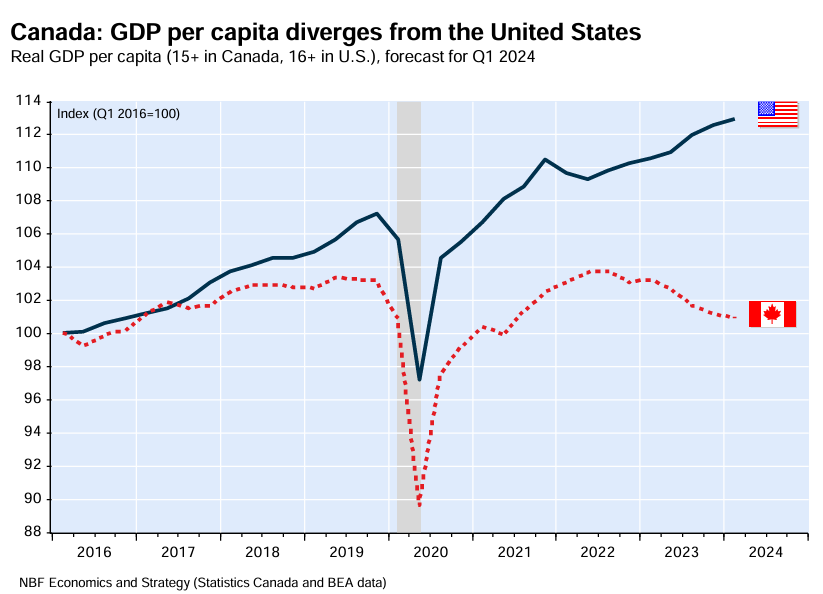

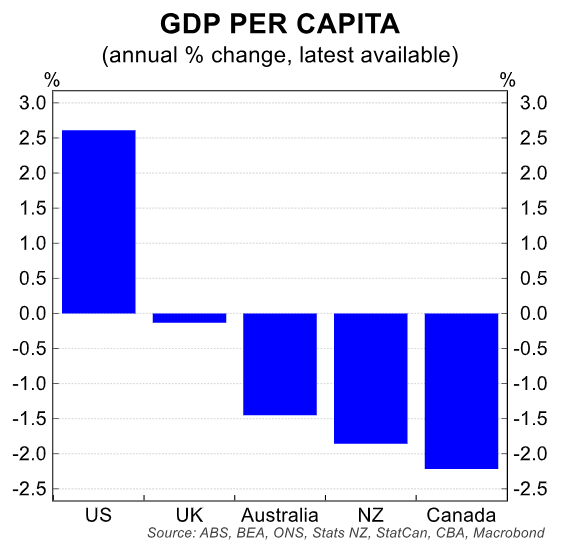

As a result, Canada’s per capita GDP has barely grown for a decade, resulting in lower material living standards:

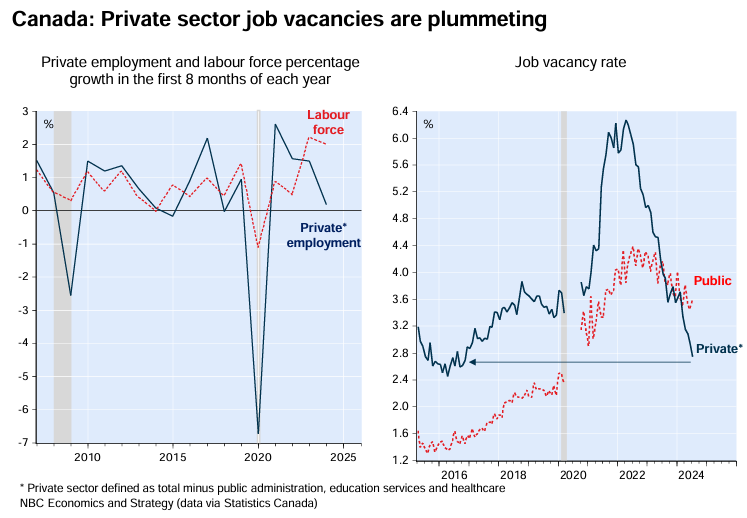

The tidal wave of migrant workers has resulted in a surplus of labour across the Canadian economy, particularly the private sector:

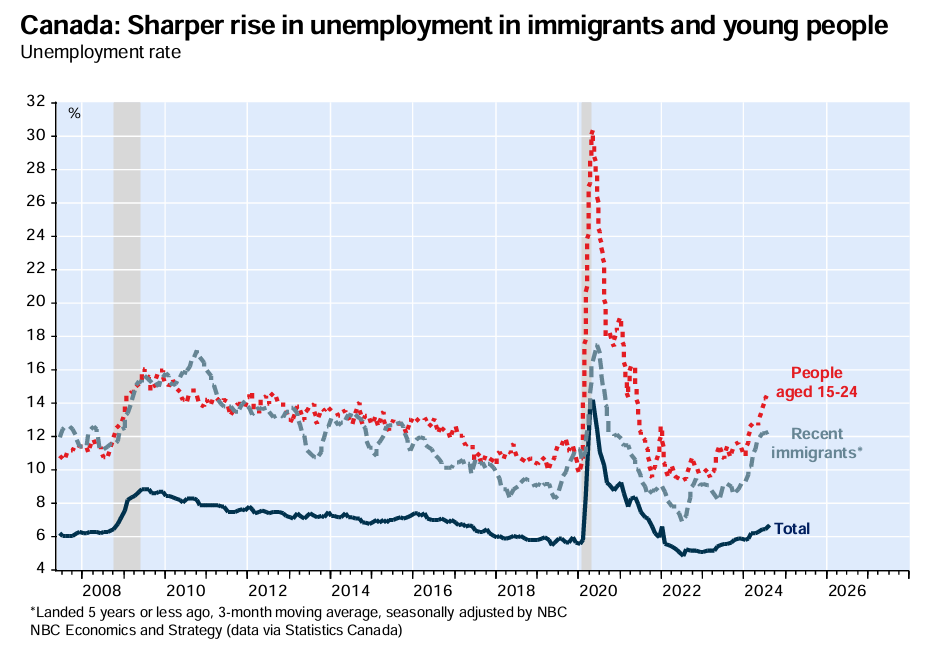

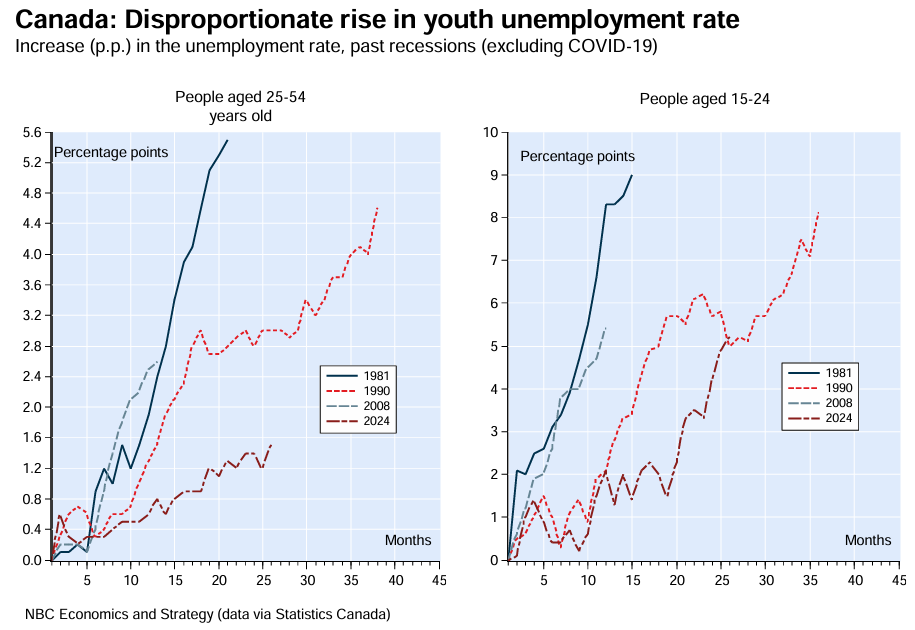

The impact has been particularly severe for young Canadians and recent migrants, who have experienced a sharp rise in unemployment:

“No fewer than 13 out of 15 sectors recorded a fall in output per employee between Q3 2022 and Q2 2024, a sign that many parts of the economy are overstaffed”, noted economists from the National Bank of Canada in their recent monthly report.

“Those trying to enter the job market – young people and newcomers – are the main victims of Canada’s weak hiring climate”.

“Indeed, the vacancy rate in sectors that tend to absorb more young people fell from 6.1% in 2022 to just 3.3% last June, the lowest level since 2017”, the economists wrote.

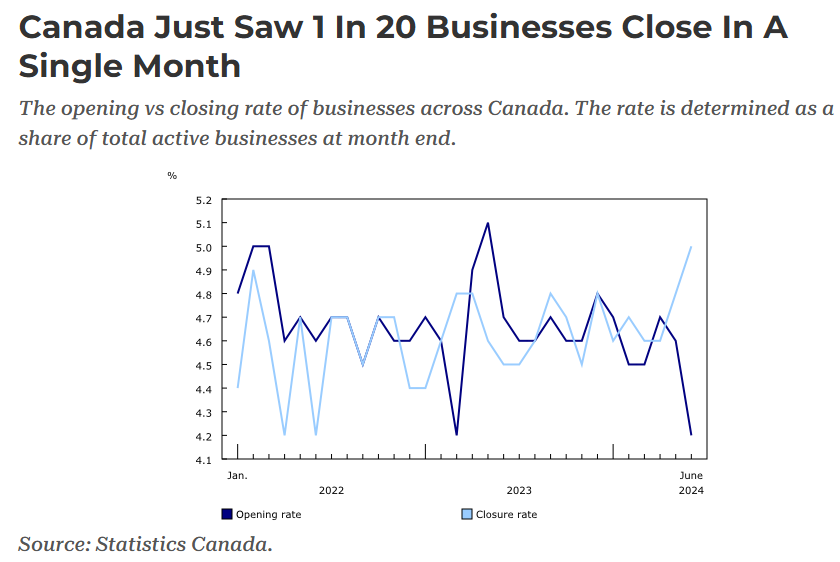

The economic malaise has spread to the business sector, where Canadian businesses are shuttering at an alarming rate.

46,354 Canadian businesses closed in June in seasonally adjusted terms, marking the largest wave of closures since the beginning of the pandemic four years ago.

The closure rate (share as a total) hit a similar pandemic record, climbing to 5.0% in June. this means that one in 20 businesses closed their doors for good in June:

At the same time, fewer Canadians are opening new businesses. Monthly business openings fell 8.6% (-3,746) to 39,482 businesses in June, which was the slowest month for new business openings since March 2023.

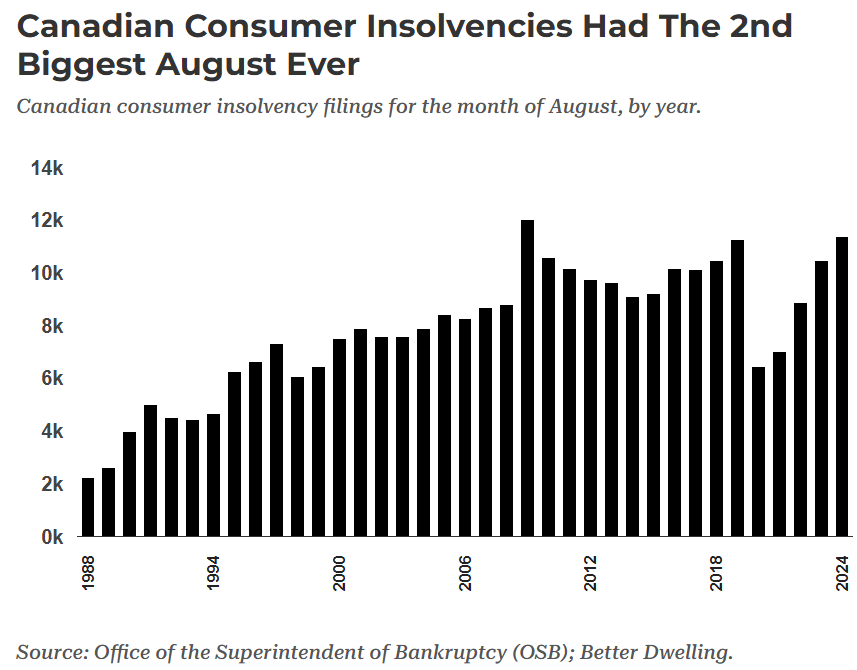

Meanwhile, Canadian Consumer Insolvencies registered their second largest monthly August increase on record behind the Global Financial Crisis in 2009:

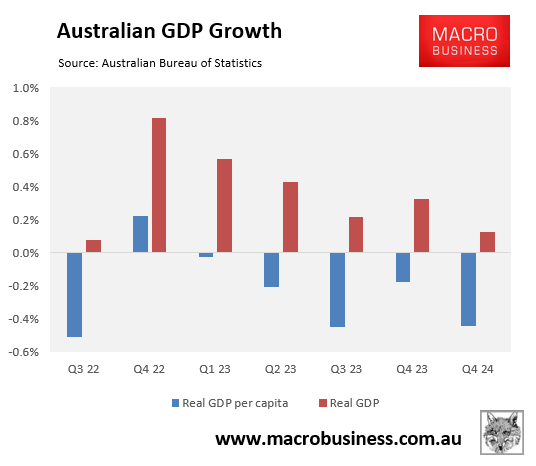

Australia’s economy is obviously in better shape than Canada’s.

Although Australia’s per capita GDP has contracted by 2.0% over eight quarters, the decline pales against Canada, where per capita GDP has flatlined for a decade.

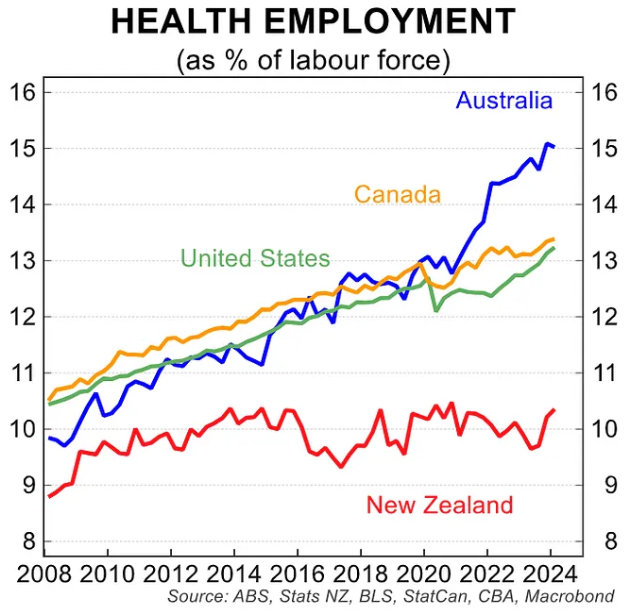

Australia’s labour market is also holding up far better than Canada’s, owing in part to the surge in NDIS-related jobs.

That said, there are clear parallels and warning signs for Australia.

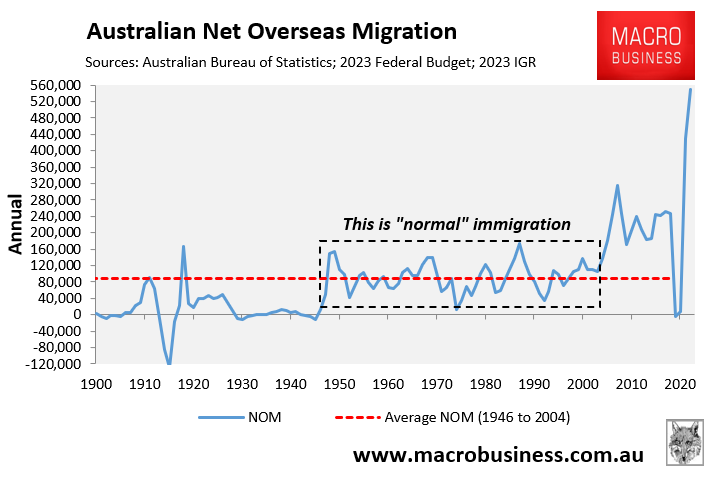

Australia, like Canada, has experienced an unprecedented boom in net overseas migration, which has also created the worst rental crisis in living memory.

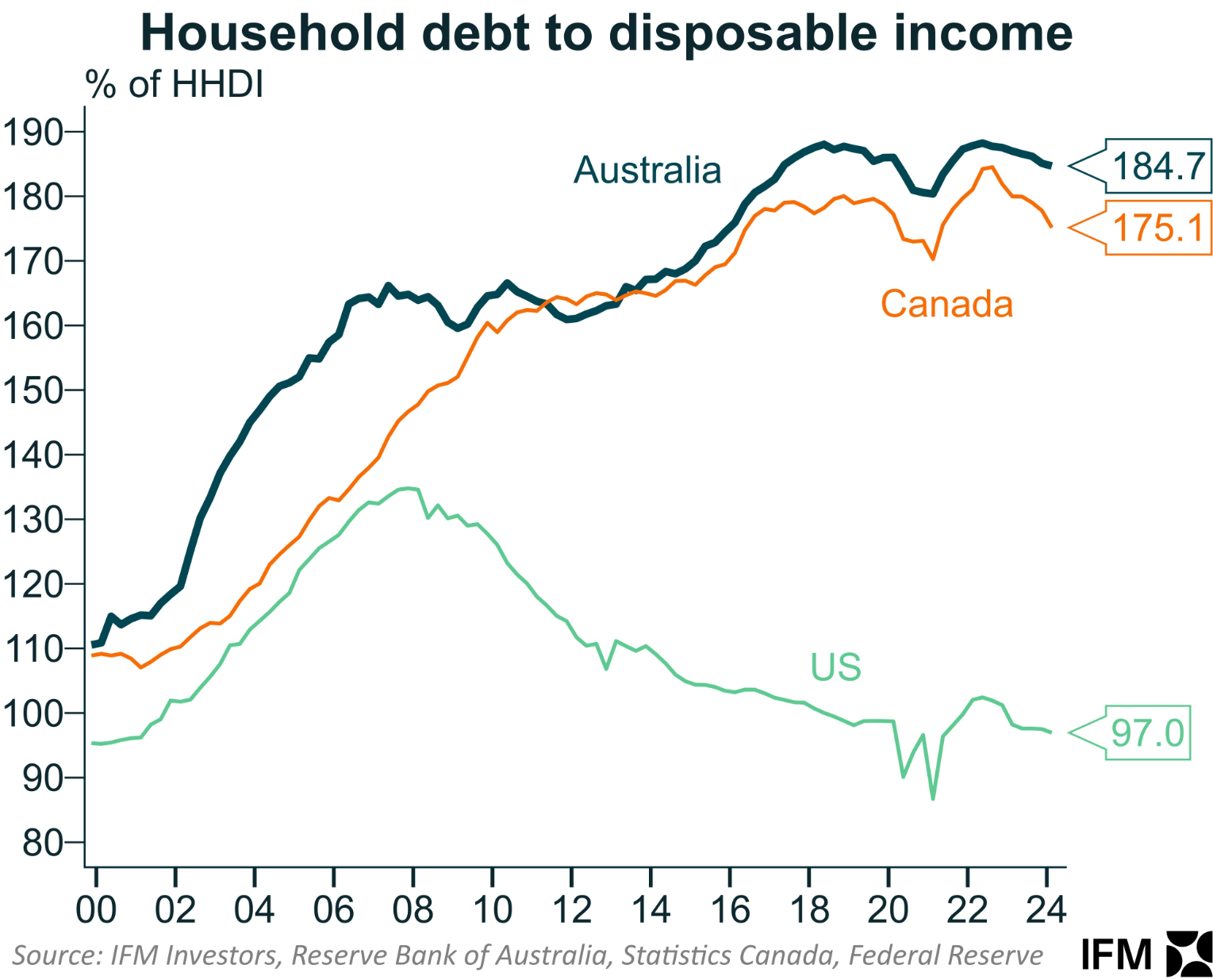

Australian households are also carrying more debt than their Canadian counterparts, placing them at risk if unemployment surges:

Australia’s productivity growth is also tracking even worse than Canada’s, driven by similar “capital shallowing” and the boom in non-market sector jobs:

The fundamental problem with both economies is that their governments have opted for lazy growth via rapid net overseas migration, which has delivered housing crises and lower productivity.

Australia should look at Canada and use it as a warning sign of what not to do. Otherwise, it risks a similar fate of collapsing living standards.