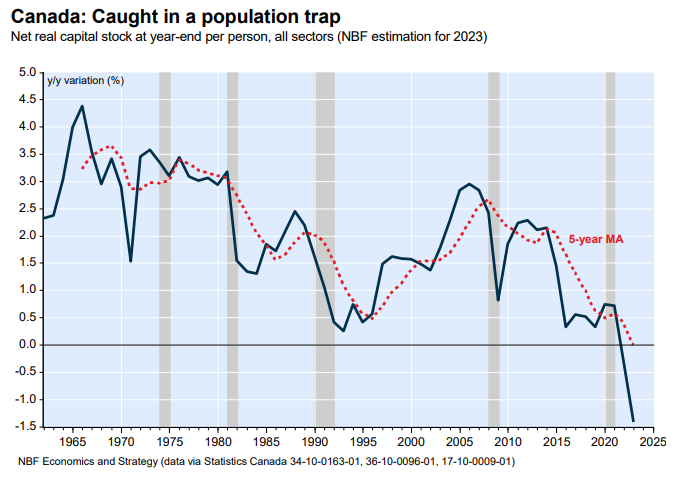

Economists at the National Bank of Canada published research arguing that Canada was caught in a “population trap” of declining productivity and living standards.

The economists noted that the nation’s population growth was “too high relative to the stock of capital available in the country”.

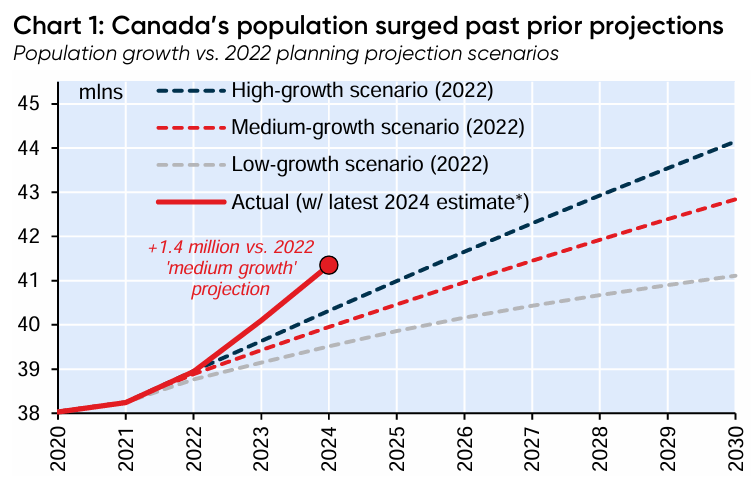

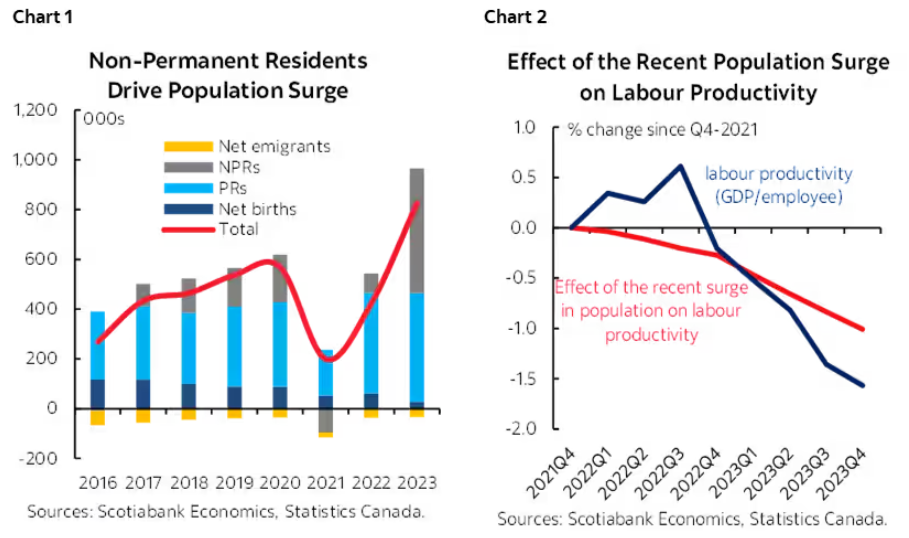

Canada’s population increased by 1.25 million in 2023, all via net overseas migration, the largest expansion in history.

The economists argued that this extreme population growth had resulted in capital shallowing because the “population is growing so fast that we do not have enough savings to stabilize our capital-labour ratio and achieve an increase in GDP per capita”.

As a result, Canada lacked “the infrastructure and capital stock… to adequately absorb current population growth and improve our standard of living”.

Their findings received support from economists at Scotiabank, who also noted that Canada’s population was expanding too quickly in comparison to business investment and infrastructure, which led to capital shallowing and decreased productivity.

They estimated that “about two-thirds of productivity declines since 2021 stem from this population shock”.

The economists also warned that if Canada remained on the same high immigration path, “the country will remain on the current trajectory of declining productivity and competitiveness”.

Scotiabank released more research this week, which estimated the “the productivity-neutral rate of population growth at around 350,000 or 0.85% annual growth”.

“In the absence of stronger investment, increases in population beyond that lower the capital to labour ratio and depress productivity”, the economists argue.

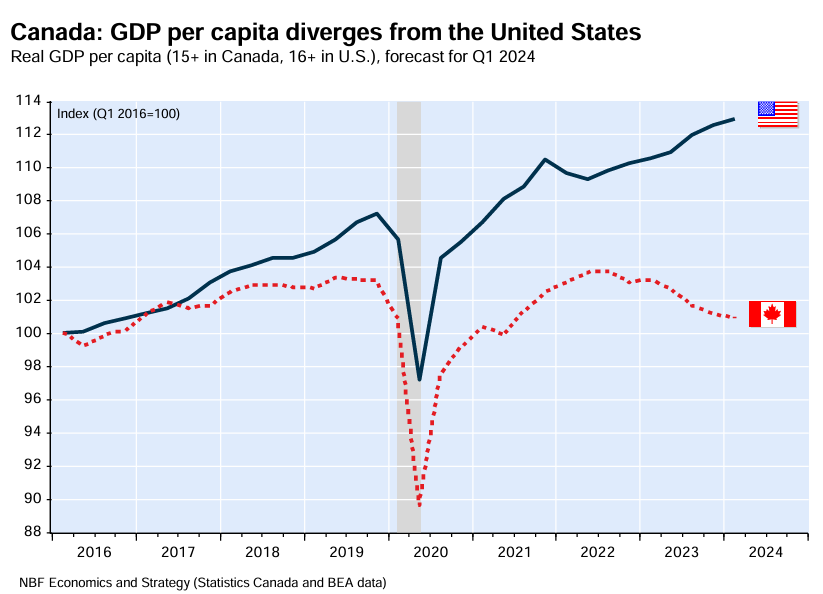

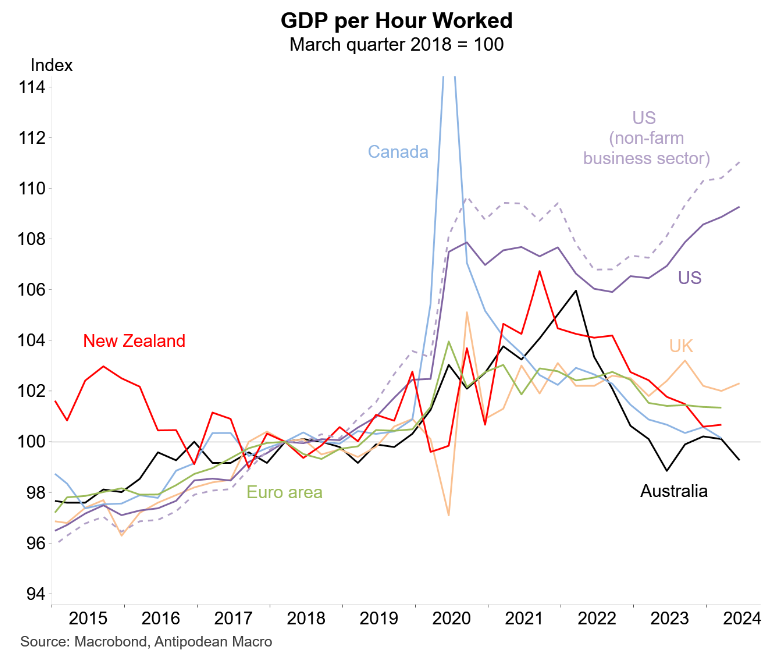

Canada’s productivity decline is best summarised by the following chart showing the stagnation in per capita GDP compared with the United States:

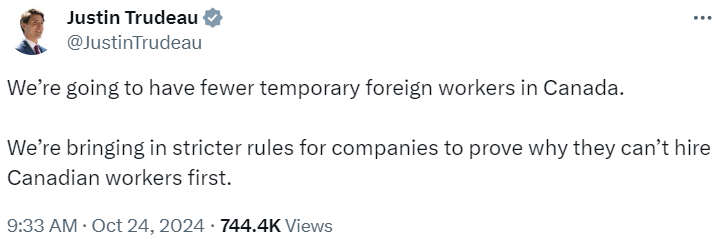

The Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, finally appears to be listening, announcing that the government would slash the number of temporary migrants:

The Canadian government also announced that it would cut the permanent migrant intake from 485,000 this year to 395,000 in 2025, alongside additional cuts in the future.

“Barring any last-minute changes, the federal government is planning to decrease permanent resident intake from 485,000 this year to 395,000 in 2025, National Post has learned. The government is planning to further cut the intake to 380,000 in 2026 and 365,000 in 2027”.

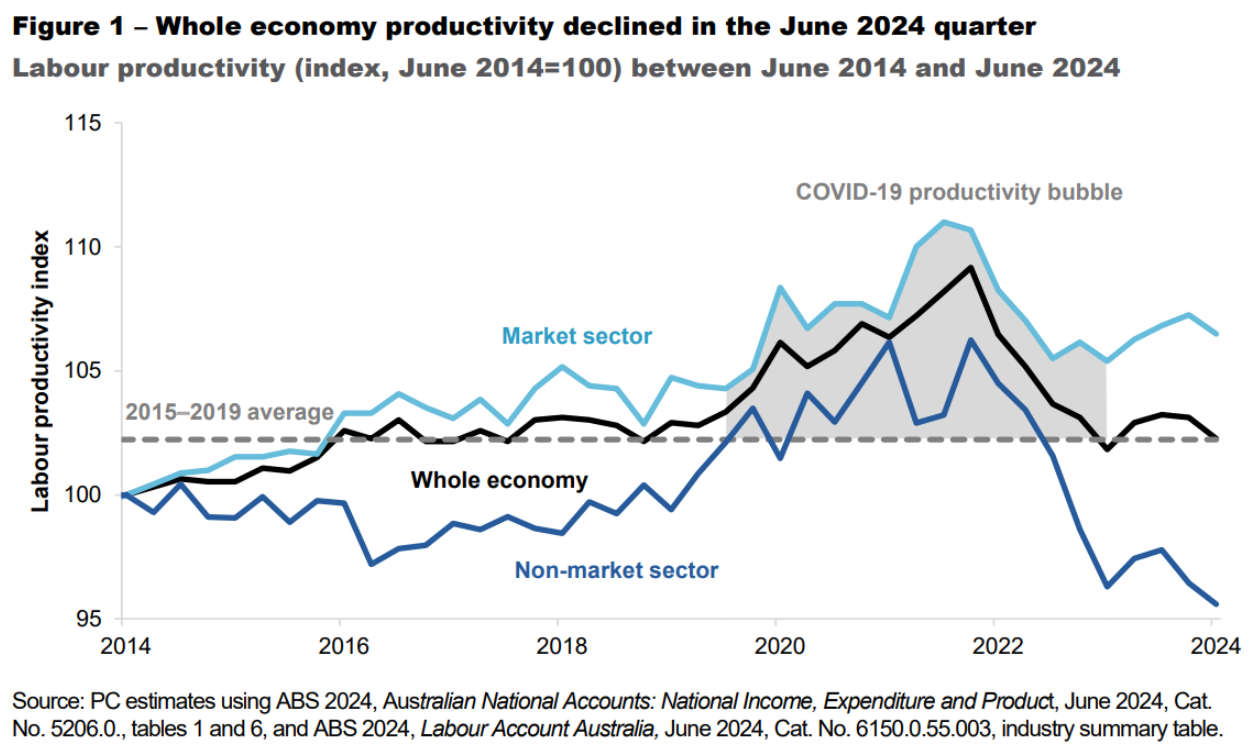

The situation is similar in Australia, where productivity growth has also collapsed.

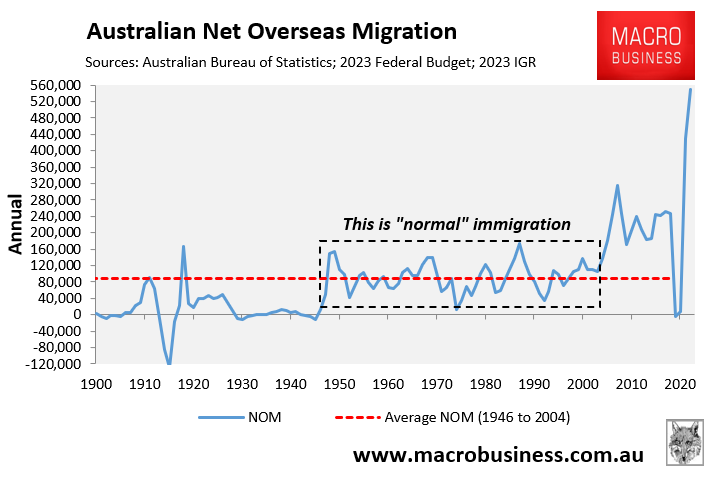

Australia ramped up immigration in the mid-2000s and has just experienced its highest ever net overseas migration:

As a result, Australia has experienced similar capital shallowing because the population has expanded at a faster pace than business and infrastructure investment:

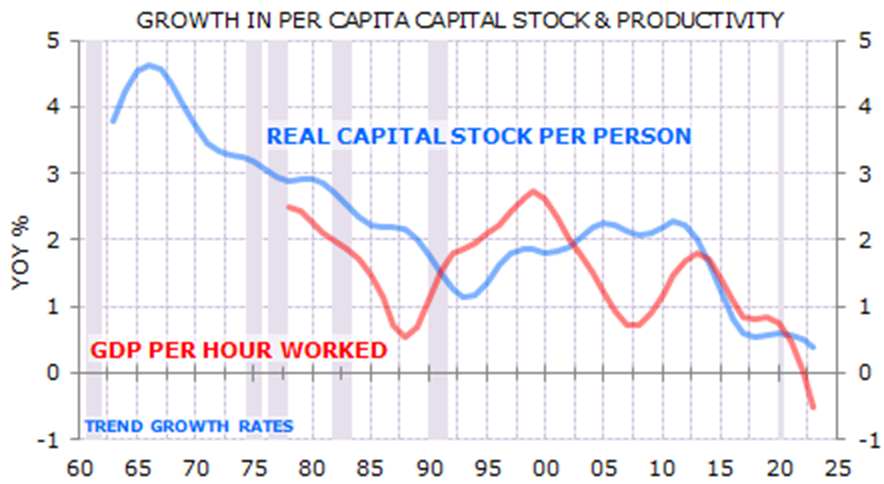

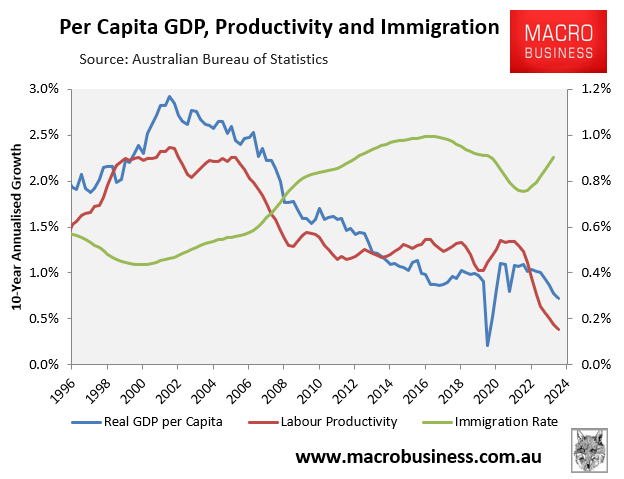

Reflecting this capital shallowing, the surge in net overseas migration in the mid-2000s was associated with a commensurate decline in productivity and per capita GDP growth:

The Albanese government has committed to lowering net overseas migration to pre-pandemic levels, which is still too high and will continue to drain productivity.

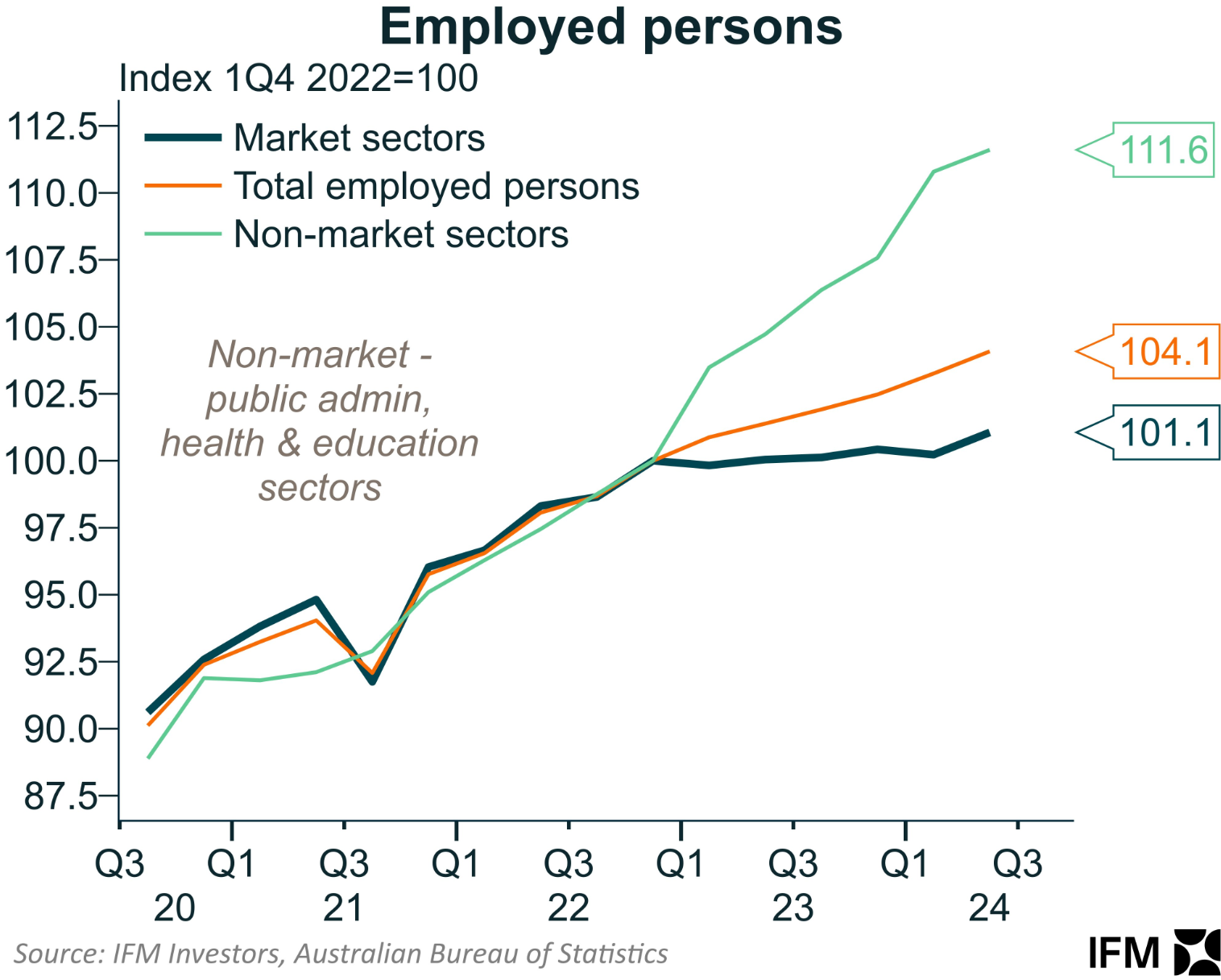

To add insult to injury, Australia’s economy is also experiencing a boom in non-market (government-aligned) jobs, courtesy of the expansion of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The upshot is that Australian productivity growth will remain poor, given that the non-market sector has historically experienced much slower productivity growth than the market sector.

Unless Canada and Australia slash immigration and lessen their dependence on government spending, they will remain on a path of low productivity, low per capita growth, and falling living standards.