Last month, The Guardian reported that cheating was widespread at Australia’s universities, driven by the surge in international students:

The Guardian separately reported that academics working at our universities were precluded from failing poorly performing international students because it risked the sausage-factory business model:

Like Groundhog Day, another report has emerged of systemic cheating by overseas students at Australia’s most international university, the University of Sydney:

“At the University of Sydney, 999 of 1259 cases (close to 80%) of student misconduct received by the Student Affairs Unit in 2023 identified student visa holders as respondents. That’s more than 10 times the number of cases for domestic students”, wrote Joanna Panagopoulos at The Australian.

“Separate 2023 academic integrity data released by the university revealed almost 100 per cent of exam misconduct referrals to the Student Affairs Unit involved international students – with 616 relating to undergraduate students and 265 to postgraduate students”.

“There are ads everywhere in foreign social media from contract cheating providers. Many international students don’t face real consequences when caught, they just leave the course or transfer to another university, which damages the academic environment”, said Herman Chan, principal advocate at Academic Appeal Specialist, which consults with students on academic appeals and disputes.

As I documented last week, systemic cheating by international students at Australia’s universities has been a problem for more than a decade.

For example, in 2014, Fairfax implicated “functionally illiterate” Chinese students in a ghostwriting scandal.

In 2015, Four Corners published its “Degrees of Deception” exposé, accusing international students of widespread cheating and plagiarism.

The episode detailed how Australia’s universities used dishonest education agents to falsify prospective international students’ academic credentials in order to assure their admittance into the Australian university system.

Four Corners also revealed the prevalence of soft-marking, mass-cheating, and academic bribery, all of which have contributed to a fall in educational standards by widely accepting students with limited English ability.

In the same year, scores of international students in NSW were involved in a cheating ring, prompting a reprimand from the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

In 2018, an ABC investigation accused Australian universities of lowering English-language standards in order to recruit international students, resulting in some students being unable to learn or communicate effectively, thereby encouraging cheating.

Concerns about widespread cheating on English language exams spurred international student associations to urge for more stringent supervision of overseas agents.

In 2019, Four Corners aired its “Cash Cows” exposé, which exposed widespread plagiarism and malfeasance by international students.

Following the Four Corners exposé, Murdoch University students claimed that “some international students were trying to circumvent the language gap by plagiarising their assignments or contracting outside sources for help”.

Also in 2019, the AFR claimed that “cheating has spread like wildfire” throughout Australia’s universities, driven by international students.

In 2020, the CEO of the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TESQA) promised to combat industrial-scale contract cheating, which was particularly common among international students.

Shortly after, Chinese students were involved in another cheating scandal, this time at the University of New South Wales.

In 2022, another ghostwriting controversy involving Asian students broke. This was followed later in the year by another investigation on the rise in contract cheating among international students.

Clearly, cheating by international students is a feature rather than a bug of Australia’s higher education system.

The primary issue is that Australia’s higher education system has degraded into a commodity ‘volume-based’ business, with universities and private colleges lowering standards to sell as many places as possible to international students in order to maximise revenue.

Because of the reduced entry standards, almost any international student can now study if they can afford tuition.

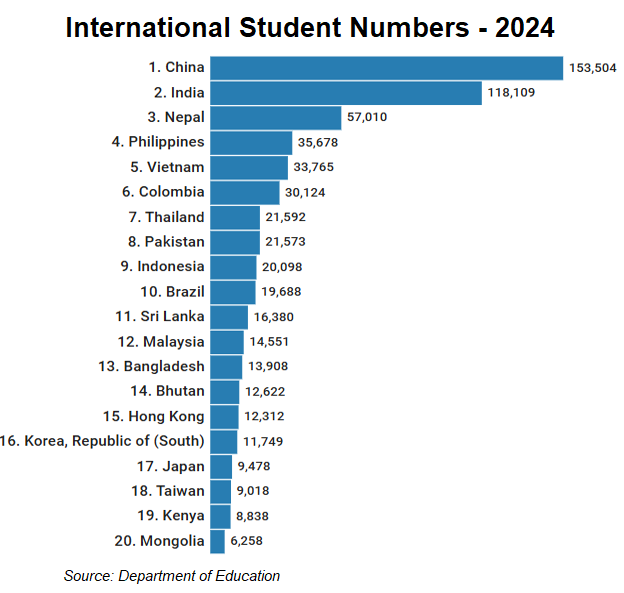

As a result, the number of students from non-English speaking nations including China, India, and Nepal has skyrocketed.

These students can only pass their written tasks if someone else finishes them. As a result, academic standards have fallen, and Australia’s higher education system has lost credibility.

University officials have likewise turned a blind eye to safeguard their prized ‘cash cow’.

The answer is to address the problem at its source by targeting a smaller intake of high-quality students, such as:

- implementing stricter English-language requirements and entrance exams;

- increasing financial requirements’ and

- removing the link between study, work, and permanent residency.

International education must evolve into a legitimate education industry rather than a people-importing immigration industry.

Students must come to Australia to study, not to gain a backdoor work visa and permanent residency.

After all, if international students cannot speak and write in English proficiently, then what is the point of them coming to Australia to study?

Of course we know the answer: to work and achieve permanent residency. The student visa is merely the cost of entry.