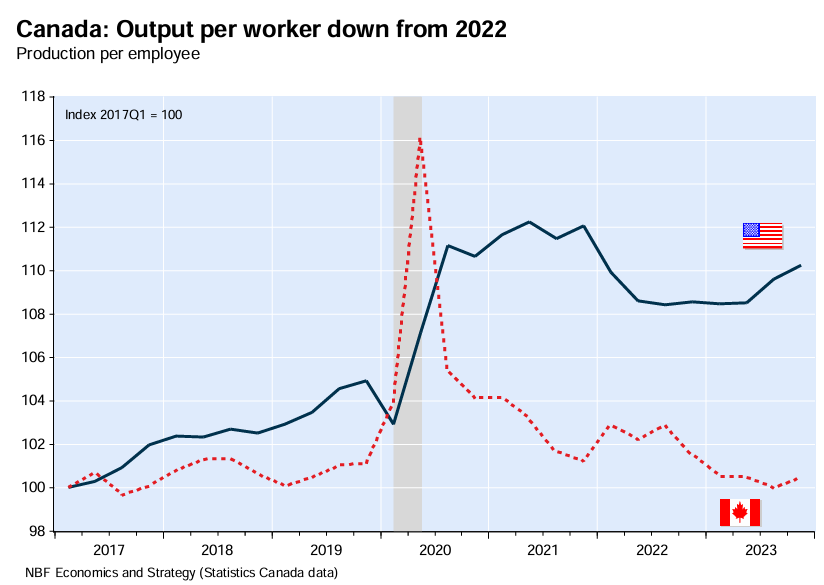

Canada has experienced a shocking decline in labour productivity in recent years, decoupling sharply from its neighbour to the south, the United States:

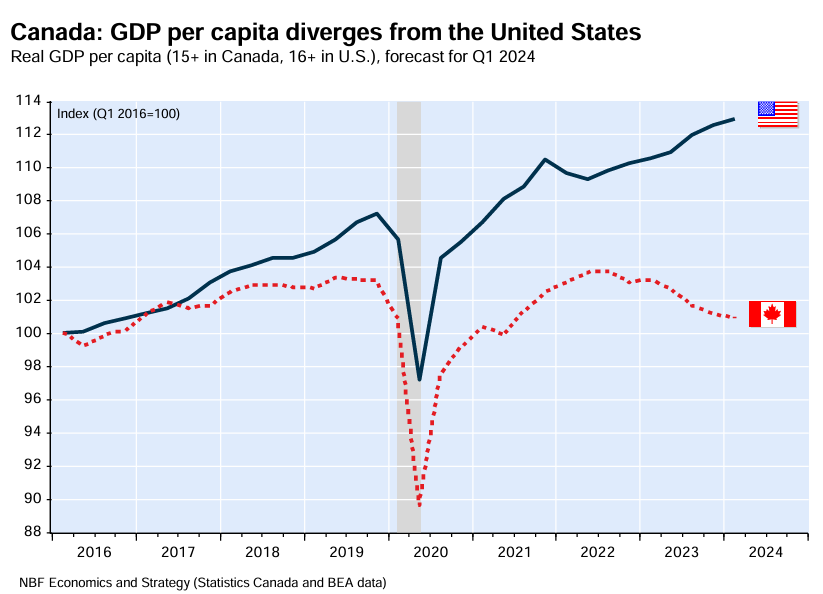

The decline in Canadian labour productivity has been matched with growth in real GDP per capita, which unlike the United States, has barely experienced any growth in a decade:

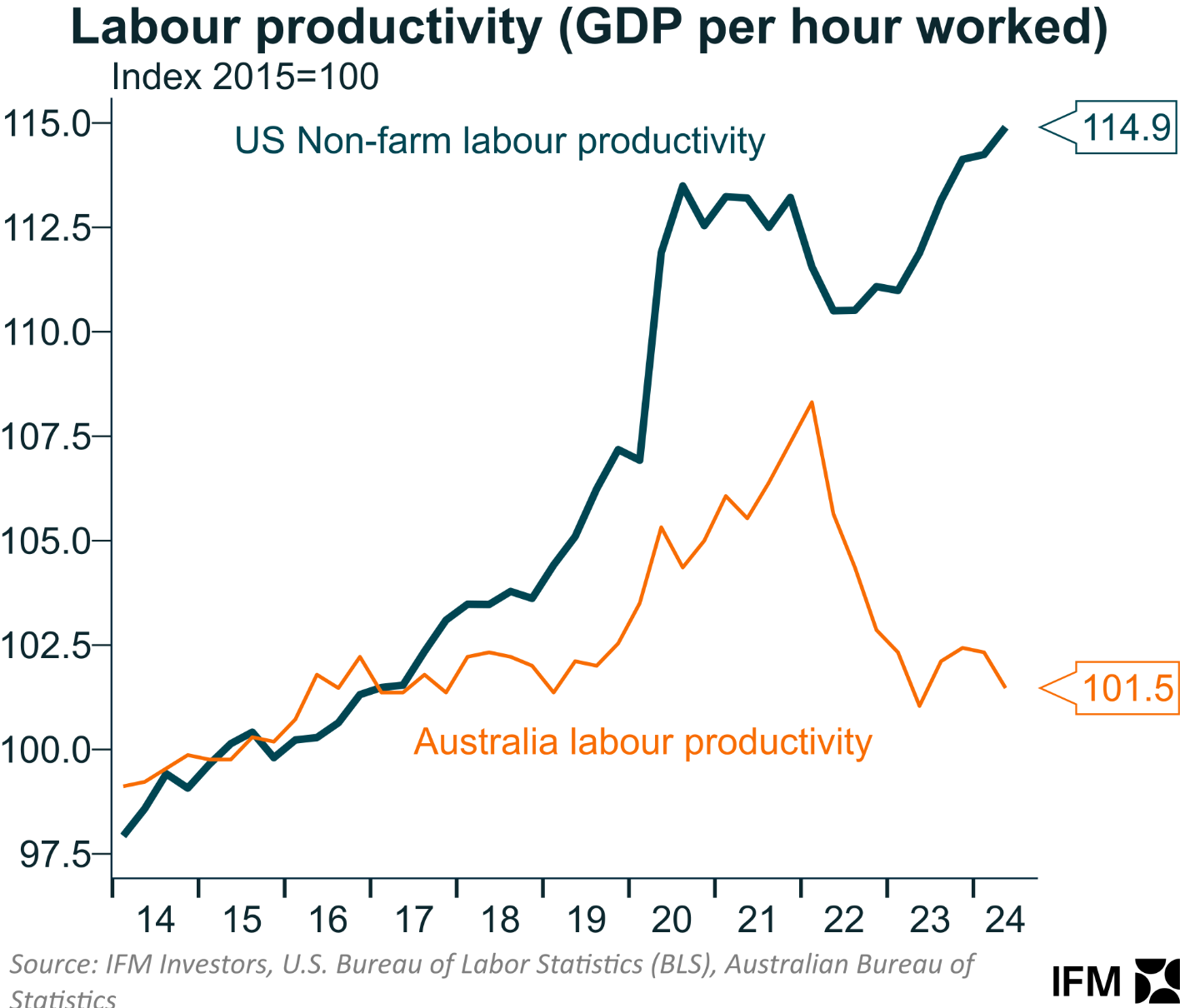

The situation is similar in Australia, where productivity growth has also plummeted, tracking at similar levels to 2016:

Arguably, one of the reasons why Canadian and Australian labour productivity has lagged so badly is because both economies have become so heavily dependent on housing and immigration to drive growth.

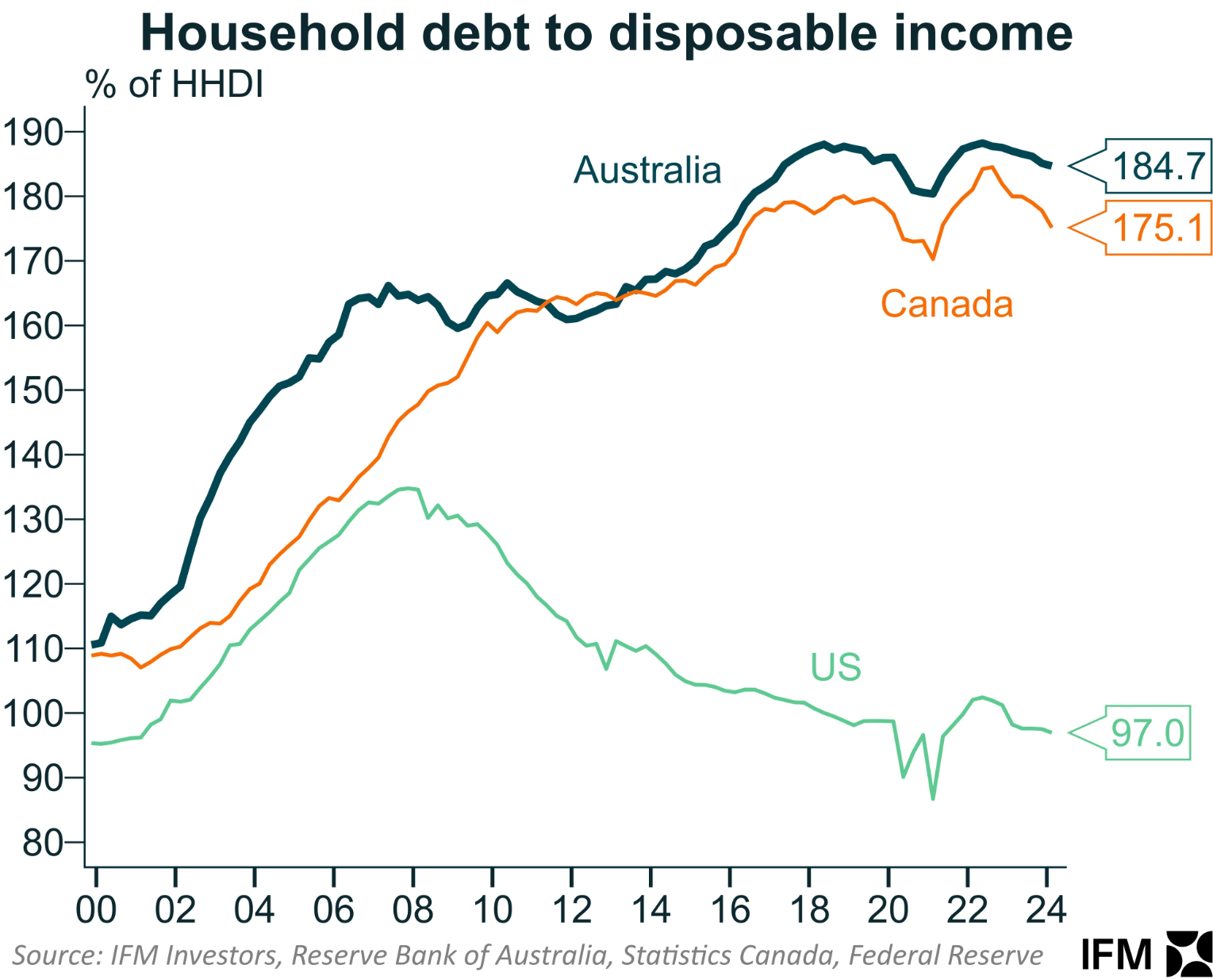

A few week’s ago, the chief economist at IFM Investors, Alex Joiner, posted the following chart showing the growth in household debt across Australia and Canada since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008:

In contrast, United States households have deleveraged since the GFC.

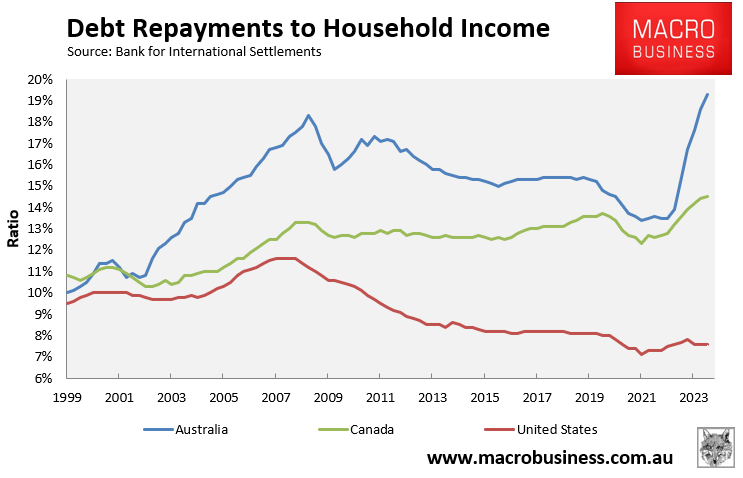

Because of these gargantuan debt loads, alongside the prevalence of variable rate mortgages, Australians and Canadians are sacrificing a significantly larger share of their incomes to debt servicing compared to Americans:

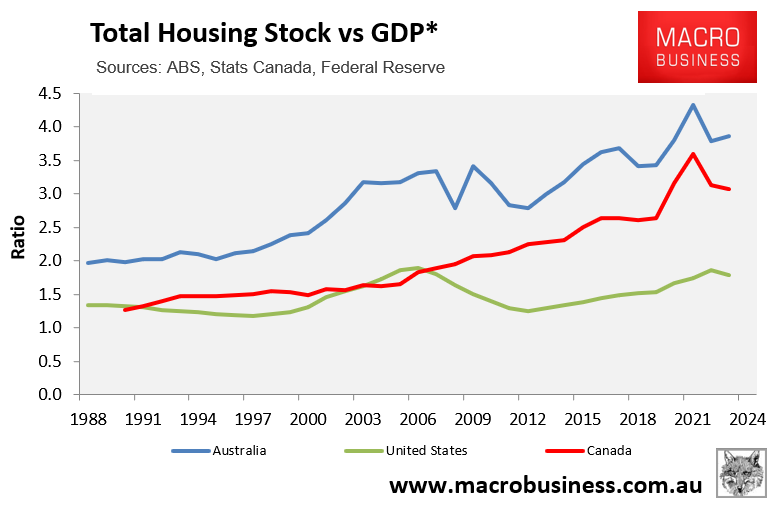

Housing valuations in Australian and Canada also dwarf the United States.

The total value of Australia’s residential housing stock was worth 3.9 times GDP in 2023, whereas residential housing was valued at 3.1 times GDP in Canada.

In contrast, residential housing was valued at only 1.8 times GDP in the United States:

Australia and Canada doubled-down on housing after the GFC, whereas the United States chose to focus on the real economy instead.

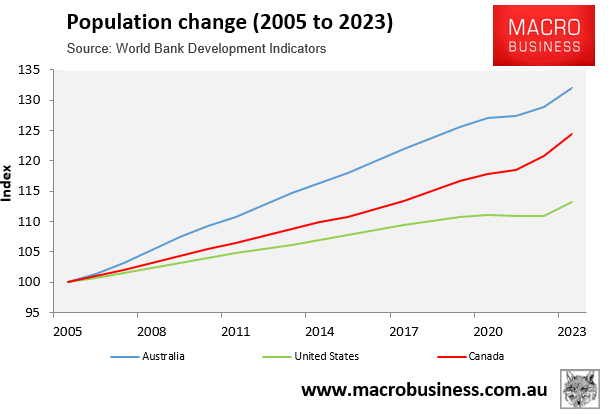

Meanwhile, Australia and Canada have grown their populations at a rapid pace through net overseas migration, whereas the United States has grown its population more moderately.

Between 2005 and 2023, Australia’s population swelled by 32% and Canada’s by 24%. Both easily eclipsed the 13% increase in the United States’ population over the same period:

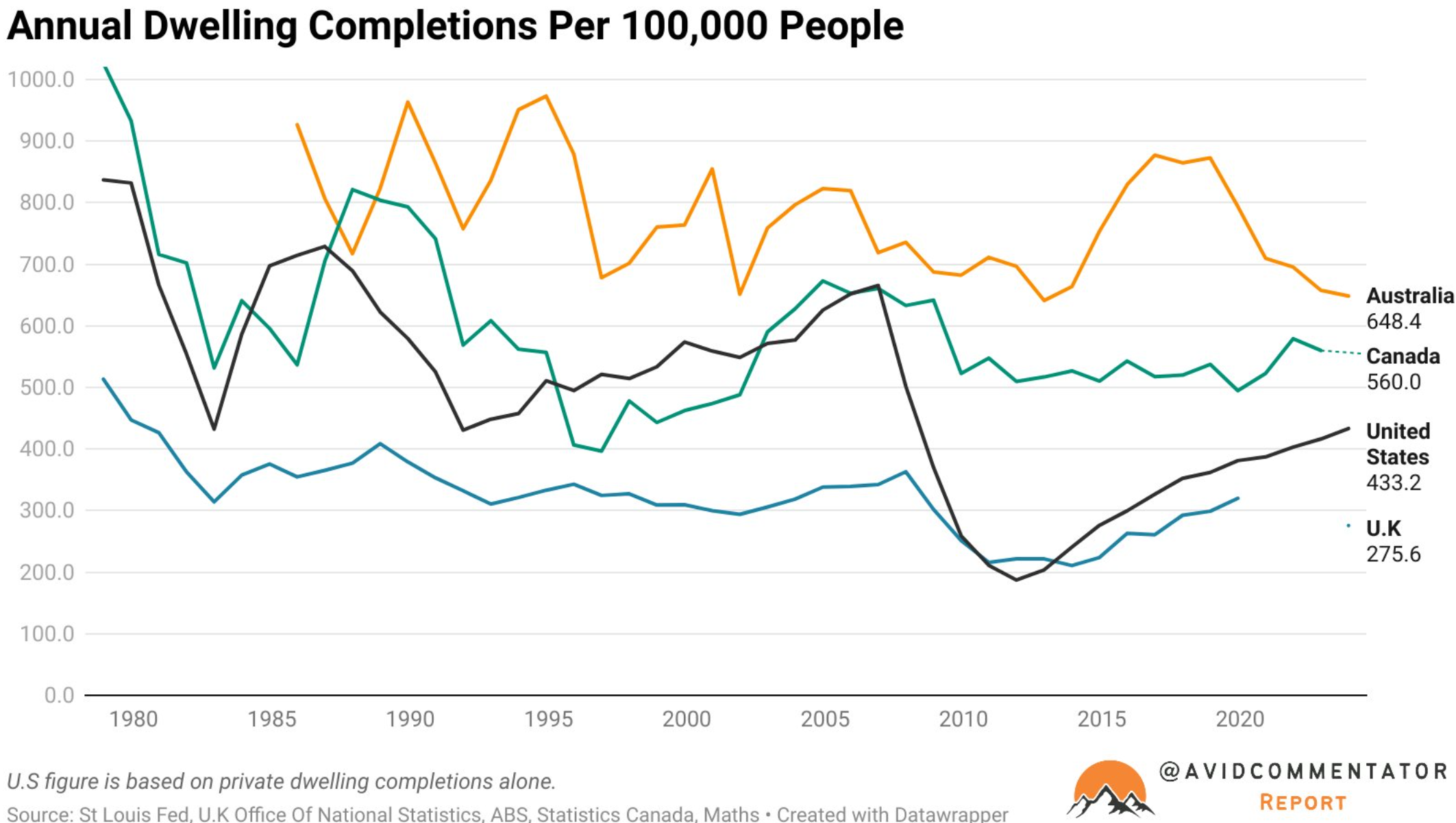

This stronger population growth has required Australia and Canada to dedicate a larger share of their economy’s output on housing construction:

Given the above data, it should not be a surprise that the United States has posted much stronger labour productivity growth than either Australia or Canada.

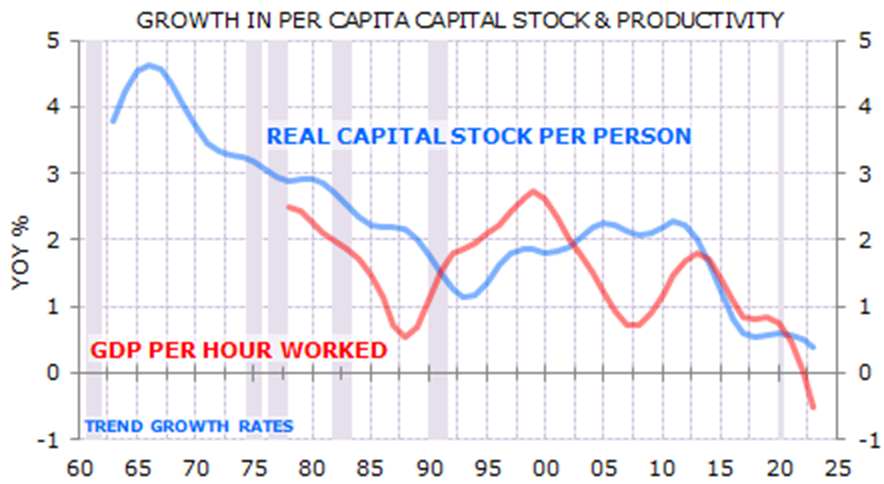

Both Australia and Canada have experienced “capital shallowing”, which occurs when business and infrastructure investments fail to keep up with population expansion, resulting in less capital per worker.

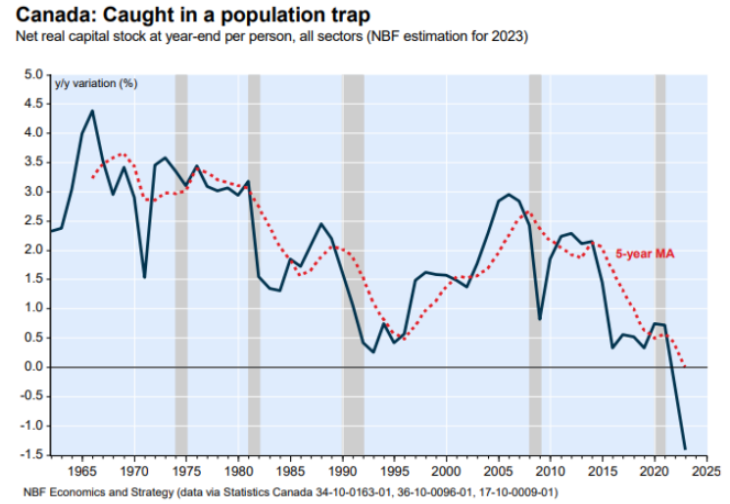

The chart below shows Canada’s capital shallowing, as reported by economists at the National Bank of Canada:

Leading independent economist Gerard Minack created a similar chart for Australia illustrating capital shallowing:

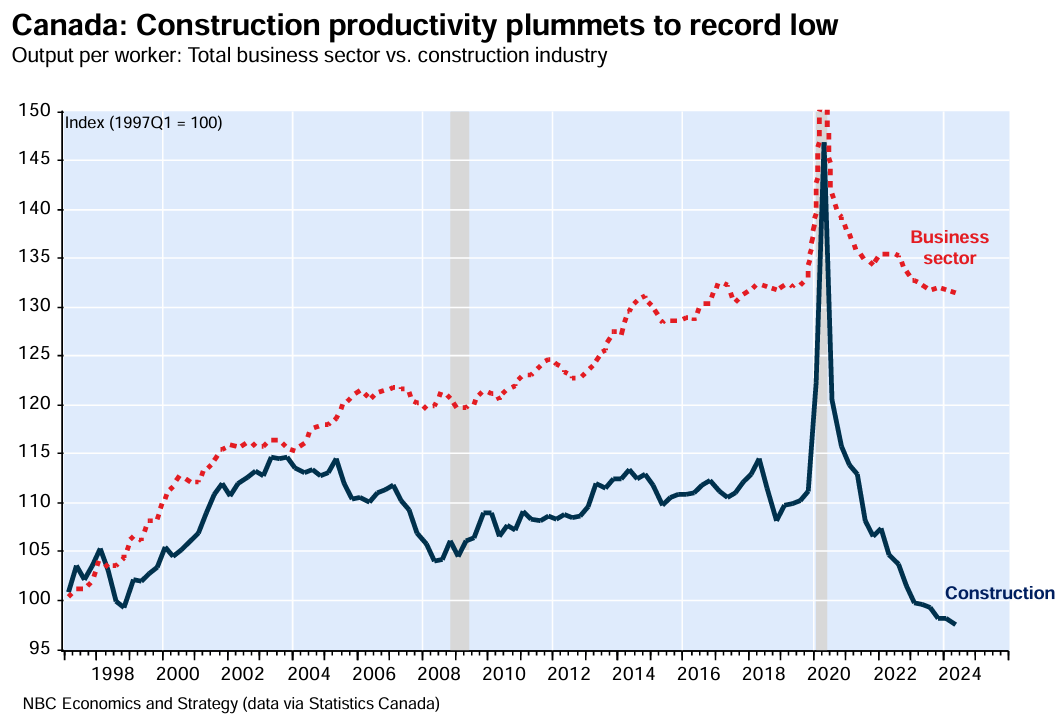

To add further insult to injury, labour productivity in Canada’s construction industry has collapsed to its lowest recorded level in Q2 2024:

“This is particularly alarming given the urgent need to build more homes in the country, with productivity in construction now lower than it was 30 years ago”, the National Bank of Canada economists wrote.

“It’s especially troubling when considering the significant funds governments plan to allocate to housing development”.

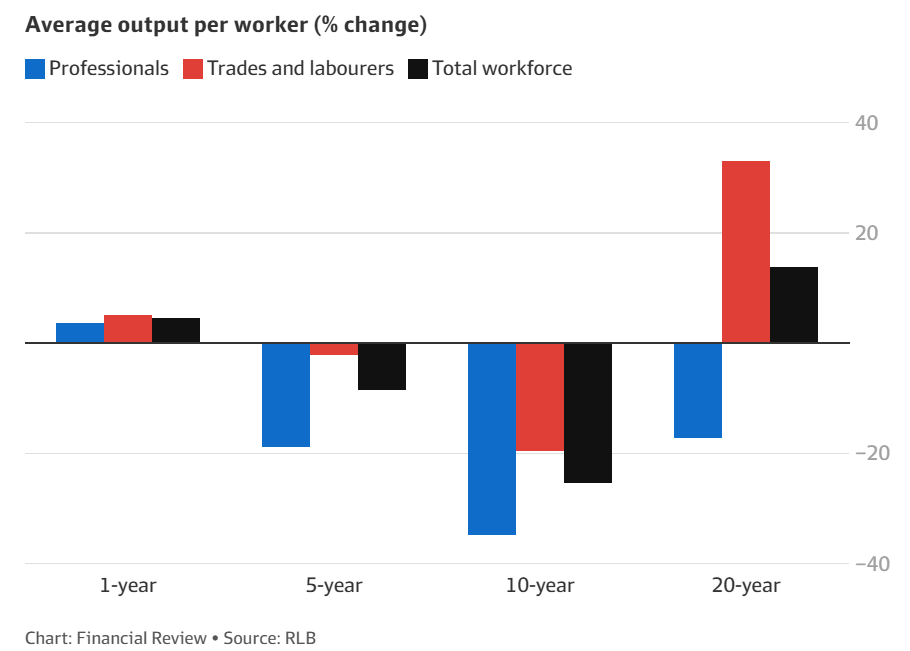

Last month, The AFR reported that multifactor productivity in Australia’s construction sector has also cratered over the past decade as the number of professionals employed surged:

Both Australia and Canada have tied their economies to housing and immigration, with deleterious results for productivity and living standards.