Over many years, I have debunked the claim that international education is a major export industry for Australia.

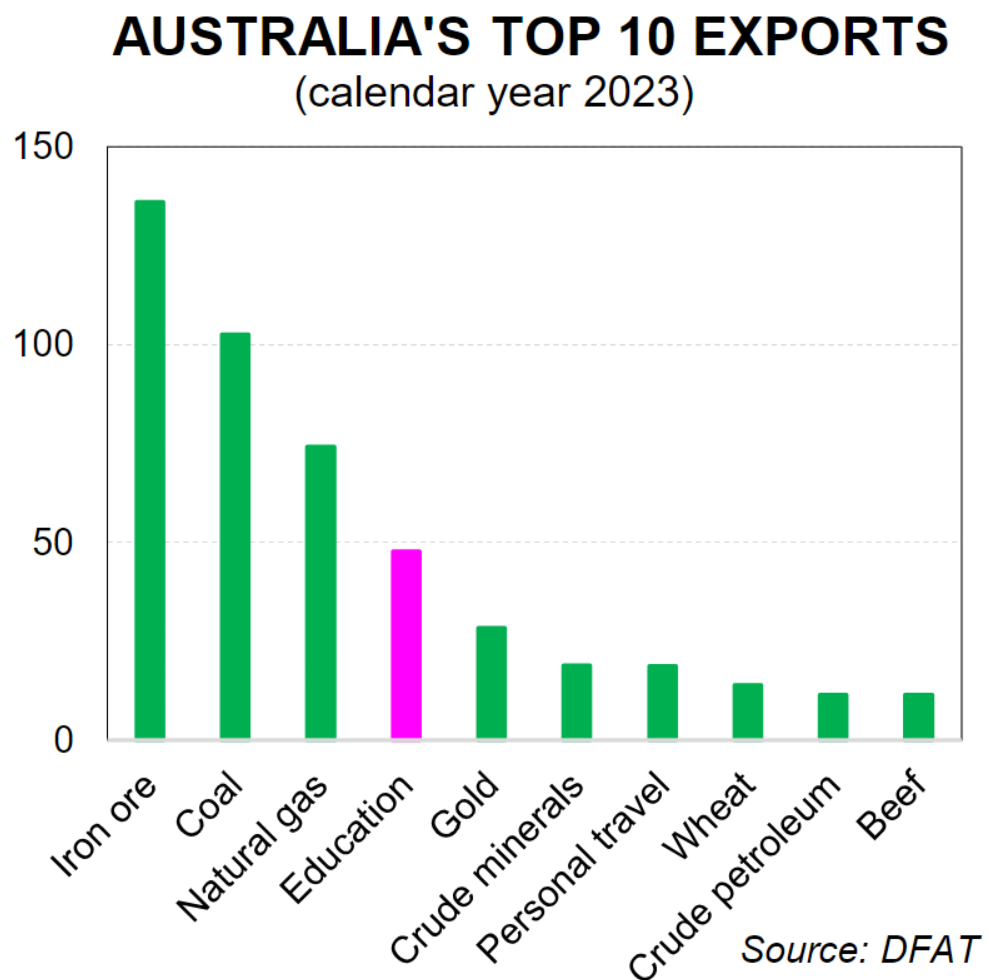

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), education is Australia’s fourth largest export valued at $48 billion currently:

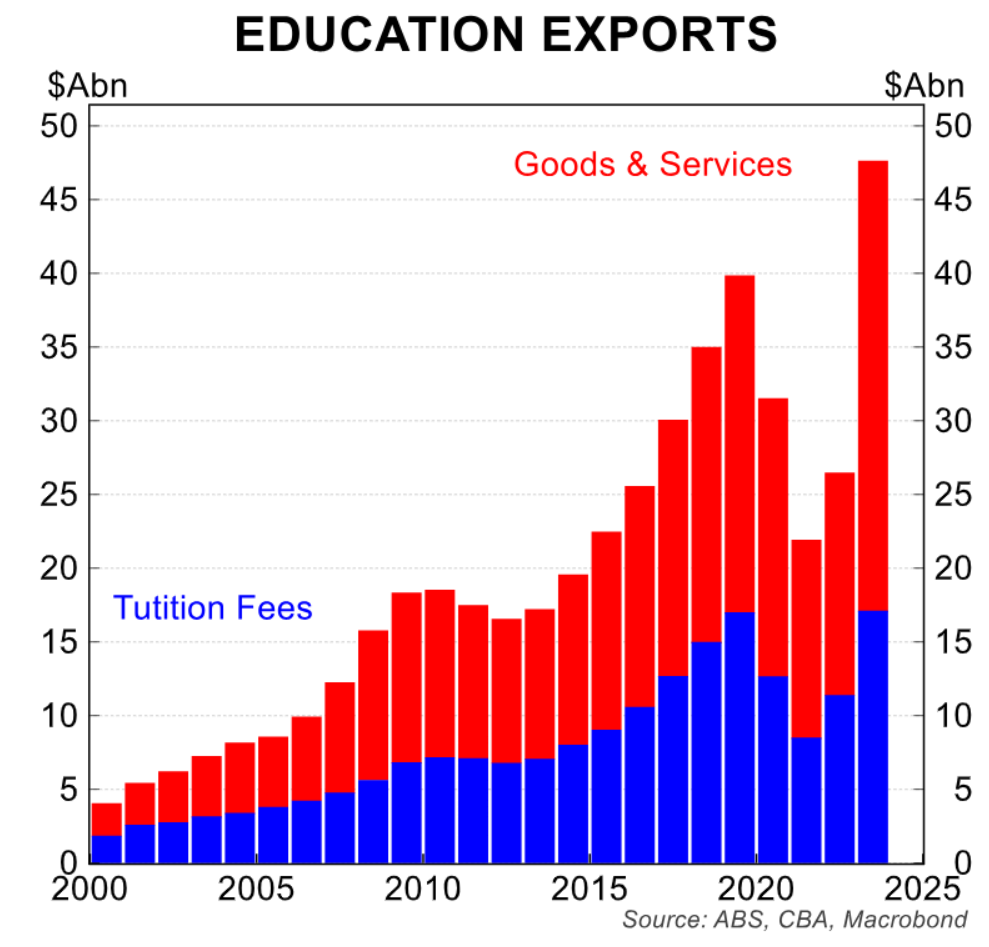

Around two thirds of these reported exports come from goods and services spending by students, with the rest coming from tuition fees:

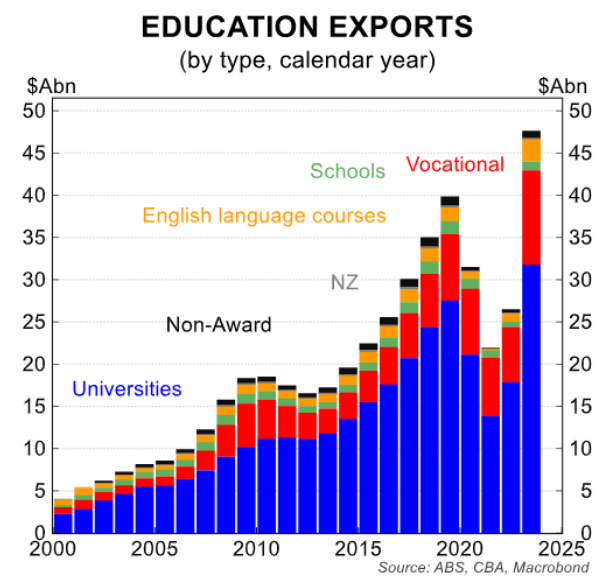

Universities and vocational colleges drive the majority of Australia’s purported education exports:

I have shown repeatedly that this $48 billion export figure is grossly overexaggerated.

First, the ABS wrongly counts all expenditure by those on student visas as an export even when the money used to pay for those exports is earned by working in Australia.

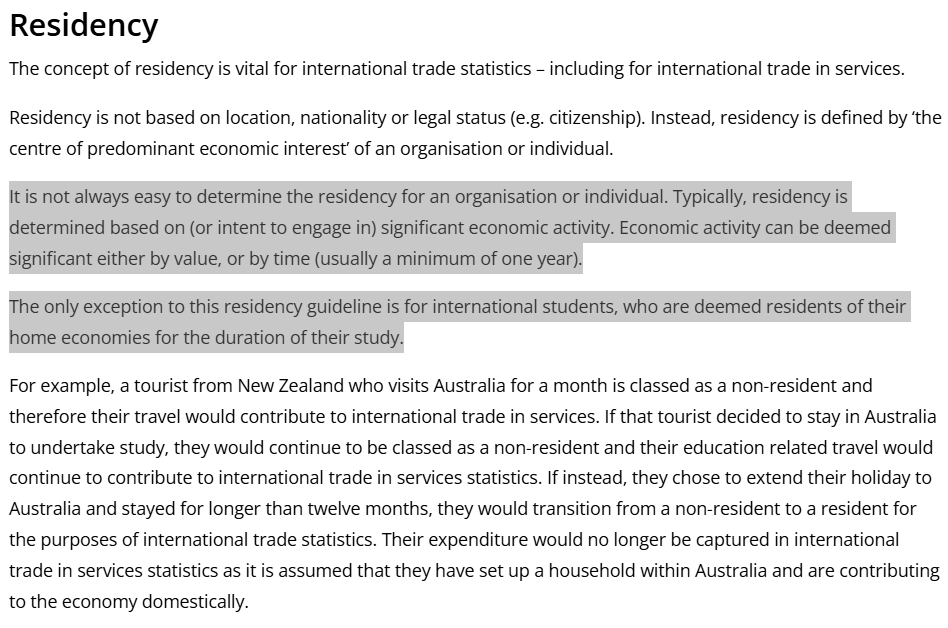

Second, the ABS treats those on student visas as non-residents for the duration of their visa—a treatment that is not ascribed to other visa holders. From the ABS website:

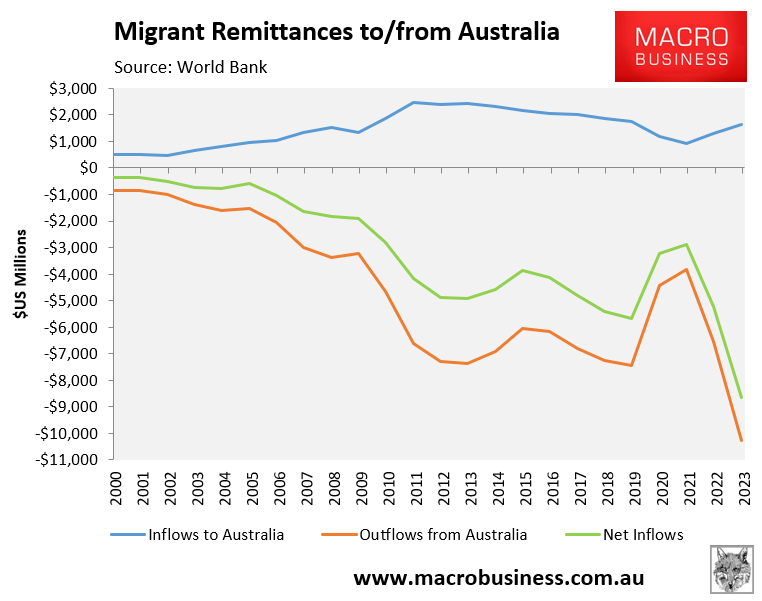

Third, how can education be considered a $48 billion export when migrant remittance data from the World Bank shows that Australia lost $US8.6 billion in 2023 in net remittances and inbound remittances are lower today than a decade ago?

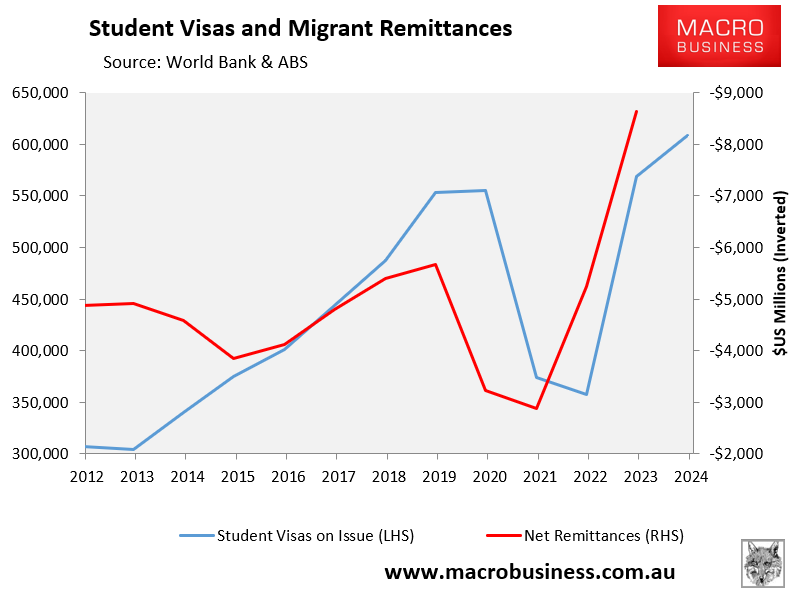

Moreover, why does the outflow in net remittances track the rise in student visas on issue:

Surely if international education was Australia’s fourth largest export industry, then Australia should be seeing a huge inflow of migrant remittances?

Yet, following the money flows suggests that international education may in fact be an import, not an export.

Another factor that contradicts the claim that education is a major export is the large sum of money paid by educational institutions to education agents abroad, which should also be considered an import.

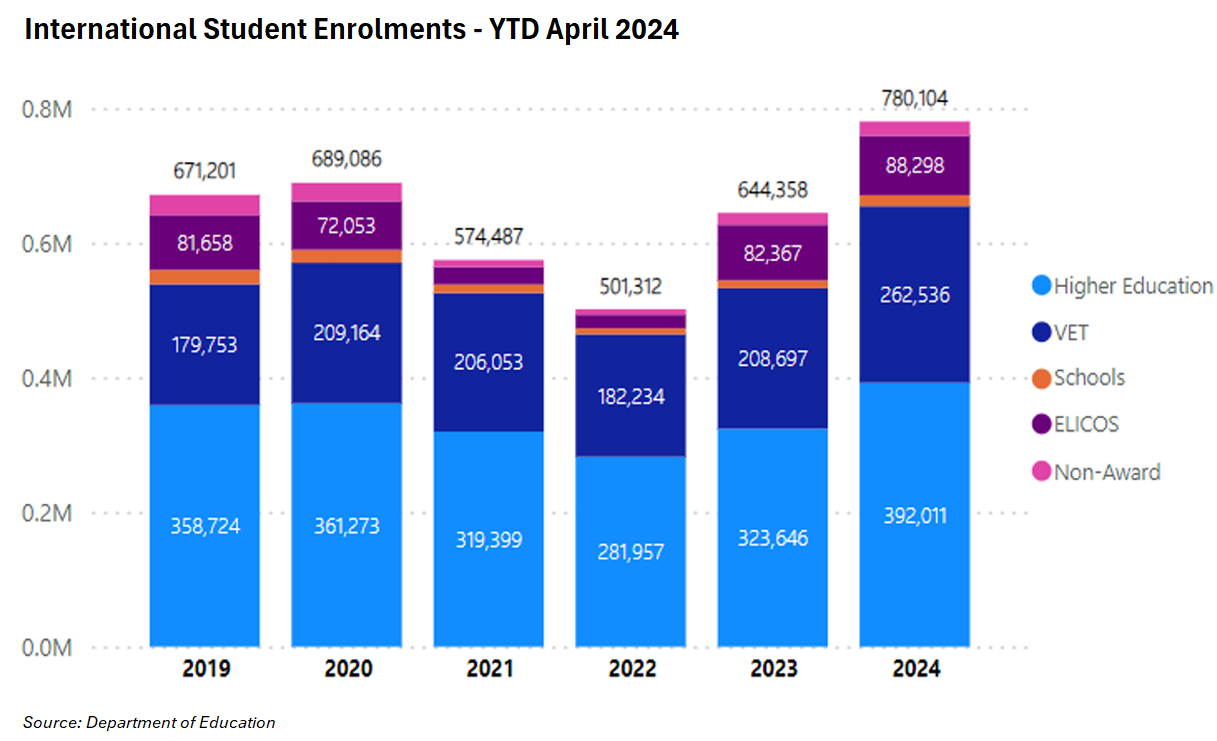

2022 was a low year for international student enrolments owing to the pandemic, as illustrated below:

Even so, NSW universities alone paid at least $147 million in commissions to education agents in 2022:

According to The SMH’s article published in December 2023:

Together, Sydney University, UNSW, UTS, Macquarie University and University of Wollongong spent $147 million on agent commissions last year, according to their financial statements and figures provided on request…

But the total figure for NSW public universities is probably far higher. Western Sydney University, University of New England, Newcastle University, Southern Cross University and Charles Sturt University refused to reveal their commission spending or did not respond by deadline…

About 76% of 2022 international student enrolments at universities came to Australia through education agents, according to the latest federal government data, up from 61% 10 years ago…

No university revealed the percentage of international student fees it paid to agents in commission, but the peak body for education agents says the industry average for higher education is about 15 per cent of first-year fees…

Some students have reported being misled by unscrupulous agents who don’t disclose their high commissions and push students into courses they may not be suited to, or provide deceptive migration advice…

Given the huge rise in international student numbers since 2022, it is safe to assume that commissions paid to offshore education agents have also surged.

As usual, there is no accounting for these commissions by the ABS in its rubbery calculation of education exports.

The ABS merely assumes that education exports = (# international students x average tourist spend) + education fees:

Dr Cameron Murray delved into the rubbery calculation of education exports at Fresh Economic Thinking.

This issue matters because the education lobby, the media, and the government have used this erroneous export figure as fuel to argue for the largest concentration of international students in the world.

However, their argument is based on statistical trickery.