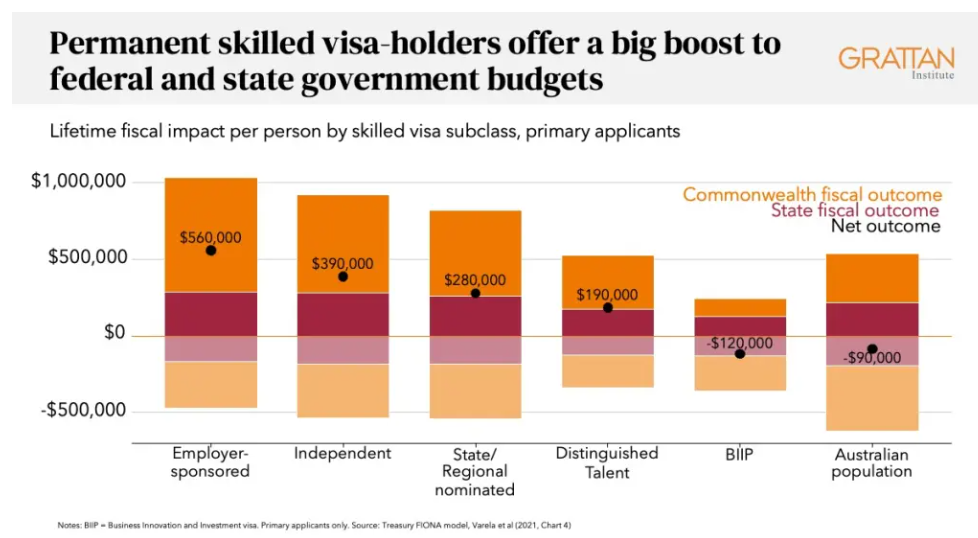

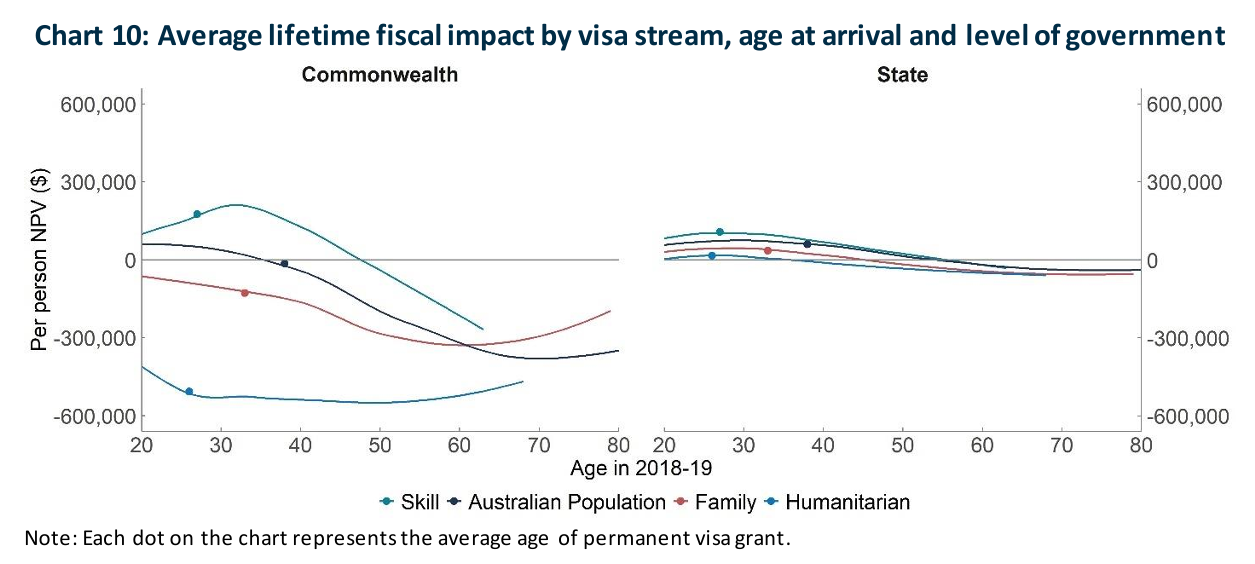

The 2021 Intergenerational Report (IGR) contained the following fantastical chart showing that each primary skilled migrant delivers $319,000 in net benefits to the Australian government, whereas every other permanent visa class (comprising more than 60% of the intake) costs the government money on average:

There were some important caveats to this analysis.

First, the 2021 IGR explicitly ignored the costs imposed on state budgets from providing the many goods and services required to sustain larger populations (e.g., infrastructure, education and social services):

“The OLGA [OverLapping Generations model of the Australian economy] and FIONA [Fiscal Impact of New Australians] results presented in this report do not capture the broader economic, social or environmental effects of migration such as technology spillovers or congestion”.

“The FIONA results presented here do not capture the fiscal impacts of migration on state or local governments”.

As a result, the 2021 IGR explicitly stated that the modelling results “are best interpreted as relativities rather than in absolute terms”.

Everybody knows that immigration provides net benefits to the federal government. The federal government collects just over 80% of the nation’s tax revenues and, therefore, benefits from the uplift from personal and corporate taxes that arise from having more workers and a bigger economy.

The situation is the opposite at the state level. State and local budgets are financial losers from immigration since they collect just under 20% of the nation’s tax revenue but are primarily responsible for providing most of the infrastructure and services.

Not so, says the migration shills at the Scanlon Foundation-sponsored Grattan Institute.

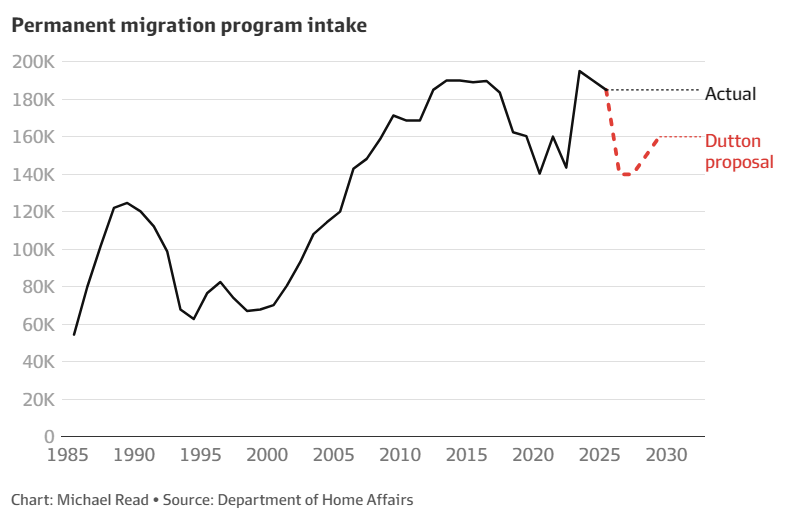

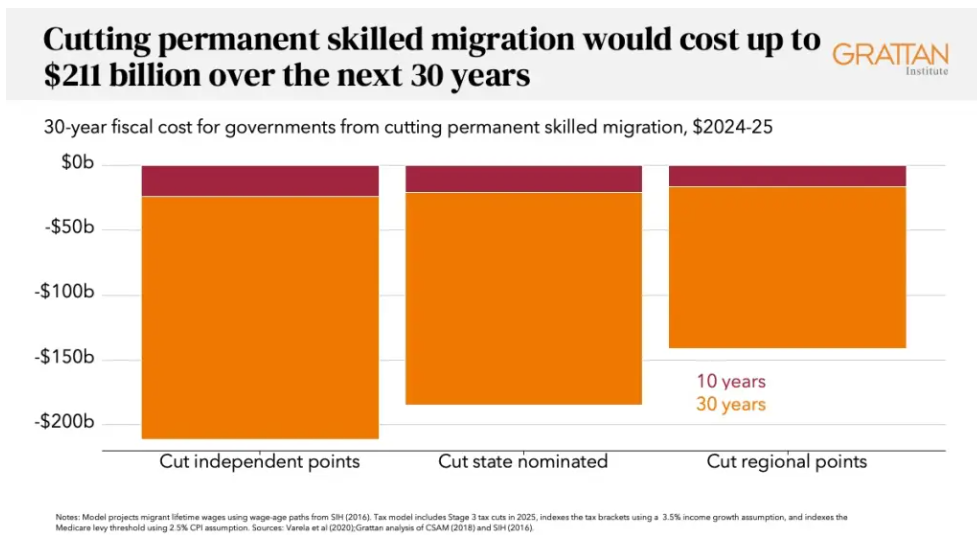

The Grattan Institute claims that Peter Dutton’s plan to modestly cut the permanent migrant intake would cost Australian government budgets (i.e., both federal and state) $211 billion in net revenue over the next 30 years, and that this loss supposedly accounts for the extra infrastructure costs associated with having a larger population:

Skilled migrants provide a large boost to government budgets over their lifetimes, because they pay more in taxes than they receive in government services. And that’s after accounting for the budgetary cost of extra spending on infrastructure and services to accommodate a larger Australian population.

Our modelling shows that every permanent skilled visa-holder offers a fiscal dividend to Australian governments of $249,000 (in today’s dollars) over their lifetimes in Australia. Therefore, reducing skilled migration by 135,000 over the next four years alone would cost Australian government budgets $34 billion in lost taxes (net of the services they draw) over those skilled migrants’ lifetimes in Australia.

But if permanent migration were to remain at 160,000 a year in the long term, compared to 185,000 intake adopted by the Albanese Government for 2024-25, the long-term costs would be far larger. We estimate that change would cost Australian governments up to $211 billion (in today’s dollars) over the next 30 years, depending on which skilled visas stream was cut.

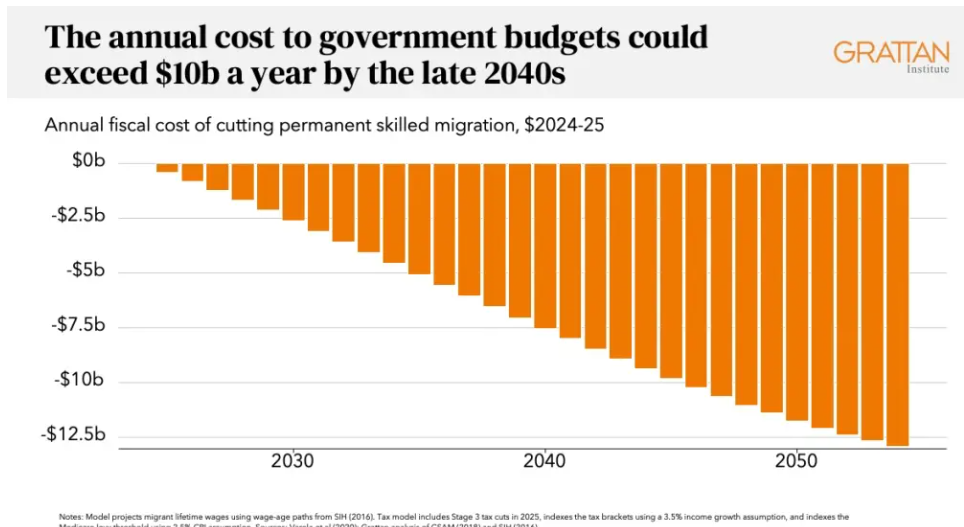

And the annual cost to Australian government budgets from cutting the permanent skilled intake could exceed $10 billion a year by the late 2040s.

You know what they say about economic modelling: “garbage in, garbage out”.

First of all, the Grattan Institute seems to be assuming that all of the migration reduction would be skilled primary applicants, even though they only account for around 40% of the total permanent migrant intake (including humanitarian). We all know that the secondary and family categories come as a package.

The “average” migrant only yielded a fiscal benefit of $41,000, according to Treasury’s FIONA report. Therefore, 135,000 fewer migrants only translates to $5.5 billion lost in taxes over four years, not the $34 billion claimed by Grattan.

Second, the model that Grattan has used to come up with its alarmist $211 billion number is an updated version of FIONA that was used in the 2021 IGR.

This version of FIONA claims that it accounts for the costs of migration for state governments as well as infrastructure costs.

However, a quick glance at Chart 10 from this modelling lays bare why it is bullshit: it calculates that permanent migrants have a mildly positive impact on state governments (see right panel below):

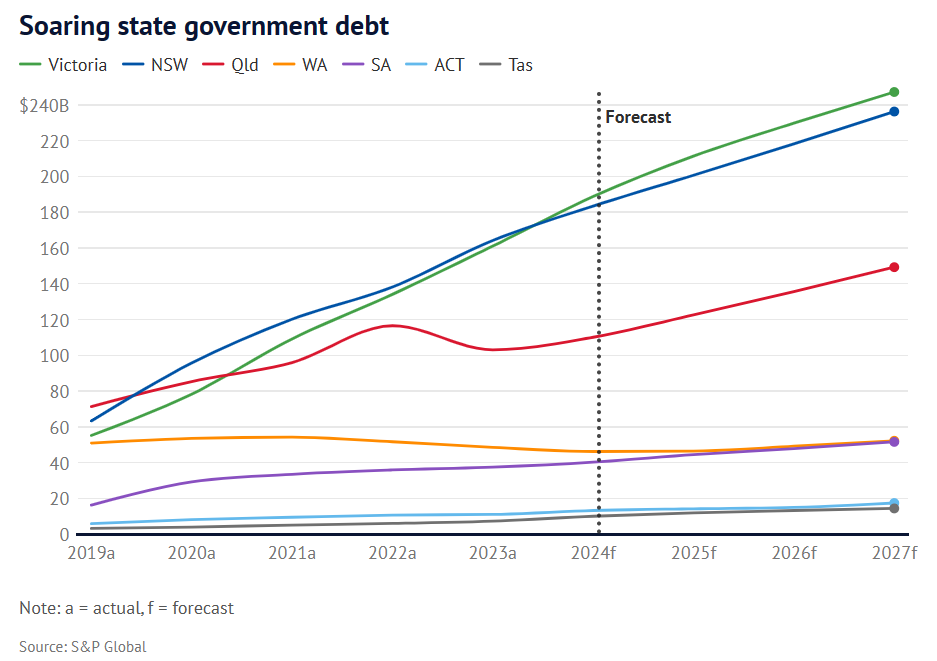

As we all know, the major access points for international migrants are NSW and Victoria. And both jurisdictions are drowning in debt, trying in vain to provide infrastructure and services to their ballooning populations:

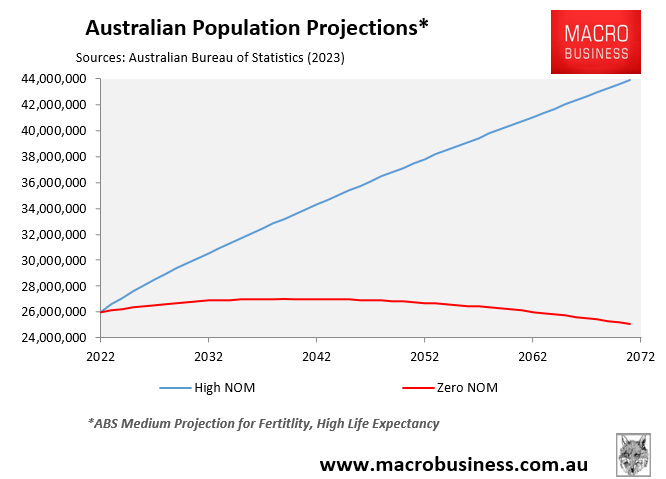

Their populations are only growing because of net overseas migration. Therefore, the full cost of new infrastructure should be attributed to these migrants.

This debt explosion has come despite these states having sold-off anything that wasn’t bolted down in a desperate bid to raise money.

As a result, residents of both NSW and Victoria have been saddled with private user charges to go along with their rising taxes.

The proliferation in Sydney’s toll roads are a case in point. Twenty years ago, you could drive around most of Sydney without having to pay tolls. Now, you cannot drive anywhere without Transurban pulling money from your wallet.

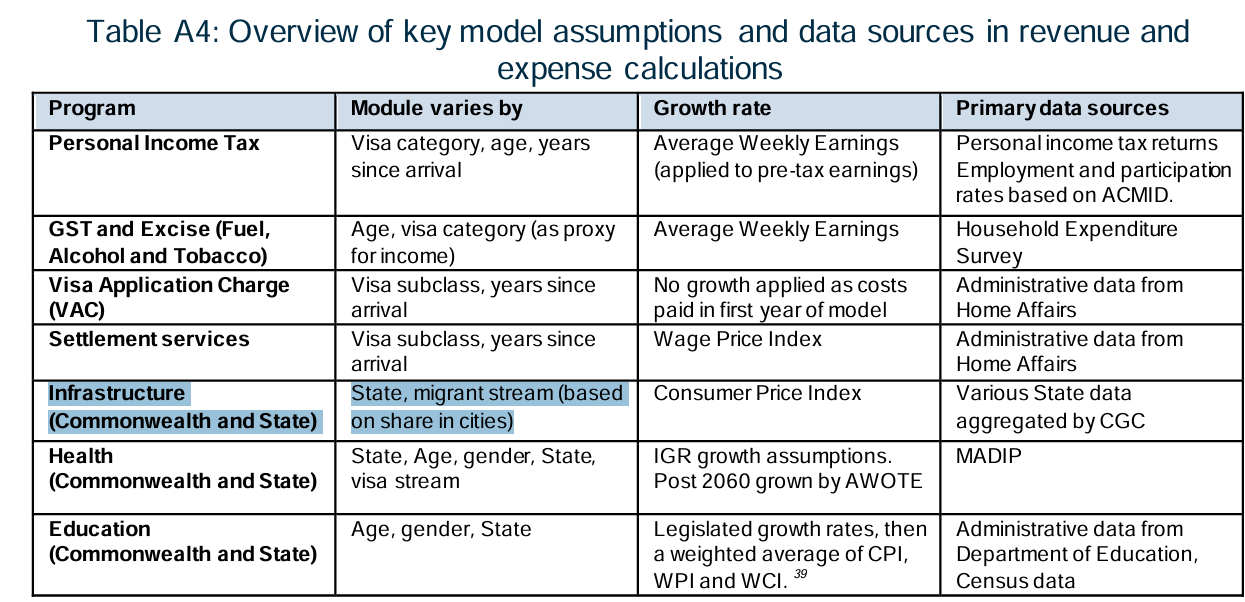

The accounting for infrastructure costs in the FIONA model is also garbage.

As explained on page 34 of the FIONA modelling, “infrastructure is assumed to exhibit constant returns to scale” and “infrastructure costs are assumed to grow in line with CPI”.

In other words, there is an assumption that the supply curve is horizontal and that bringing in more migrants doesn’t involve disproportionately more costs. Nor do infrastructure costs rise faster than inflation, according to the model.

These assumptions are highly unrealistic since infrastructure provision involves diseconomies of scale, especially because migration is concentrated in the major cities.

This means that the supply curve slopes upwards and possibly becomes even more inelastic as the migrant intake increases.

We have witnessed these diseconomies of scale firsthand in our major cities, where the cost of projects keeps blowing out due to diseconomies of scale associated with tunnelling, land buy-backs, retrofitting, and overall complexity.

Hence, state governments have been thrown deeper into debt as the costs of infrastructure continue to balloon.

Moreover, “FIONA captures infrastructure that is funded through taxation (road, transport and hospital and school infrastructure) but excludes infrastructure funded through user-charging (such as electricity networks and airports)”.

Therefore, the costs imposed on residents by privatisation and higher user charges are ignored in the model. But they are costs to Australians, regardless.

Table A4 on page 26 also states that under the FIONA model, all the infrastructure expenditure in a city is allocated to either migrants or the Australian-born based on the proportion of migrants present.

Under the model, migrants and Australians are allocated the same cost of infrastructure provision per year, but migrants incur a lower cost over their lifetime because they spend fewer years in Australia.

Then the “savings” on infrastructure for those years migrants don’t spend in Australia become part of their fiscal benefit compared with the average Australian. How convenient.

Put another way, the costs of infrastructure are attributed disproportionately to Australians because migrants spend fewer years in Australia. But if the costs attributed to children of migrants were attributed to their parents, most of the fiscal advantage would disappear.

Moreover, all of the cost of ‘capital widening’ should be allocated to the people who make the population grow (i.e., migrants and their children), because without them, we wouldn’t need to build it.

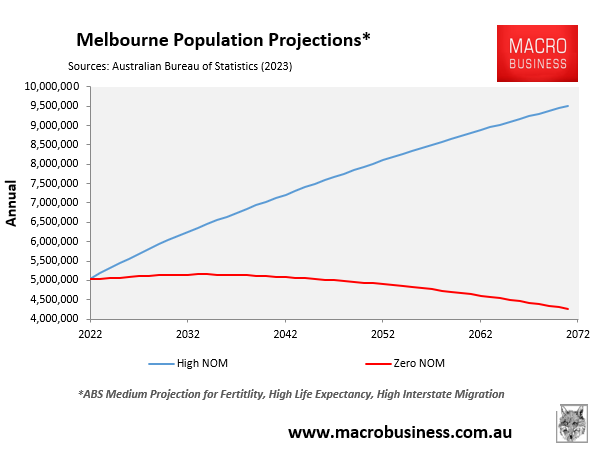

Migrants are the sole driver of population growth in our cities. Their populations would not grow without net overseas migration.

Therefore, the costs of infrastructure, which grow as the population expands, should be overwhelmingly attributed to migrants, not incumbent Australians. But the FIONA model effectively does the opposite.

For example, the reason why the Victorian government is spending more than $200 billion to build the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL) is because Melbourne’s population is projected to grow to 9 million people by 2056, due solely to net overseas migration.

Victoria wouldn’t need to build this project if it had zero net overseas migration and would save the $200 billion cost by not doing so. As such, this $200 billion cost of the SRL should be attributed to migration.

Given that Australia has experienced 20 years of high immigration, why are the roads choked, there are a shortage of hospital beds, chronic ambulance ramping, and a housing shortage?

Where have all the billions of fantastical budget gains gone? Because they certainly have not gone into infrastructure or raising the living standards of the majority of existing Australians.

Former NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet encapsulated the farce in February:

“The advantage of immigration is that it drives up revenue receipts or income tax, and it drives economic growth, but ultimately, it’s lazy economics, simply having immigration as a Ponzi scheme”, he said.

“I believe the federal government should be providing more infrastructure investment to the states”.

That doesn’t sound like migration is a boon to the states, does it?

Sadly, Grattan and the Australian Treasury never take proper account of the costs of big migration, either financial or non-financial, since these are borne primarily by the states and residents at large.

From immigration to energy, the Grattan Institute has turned into a propaganda outfit for corporate Australia.