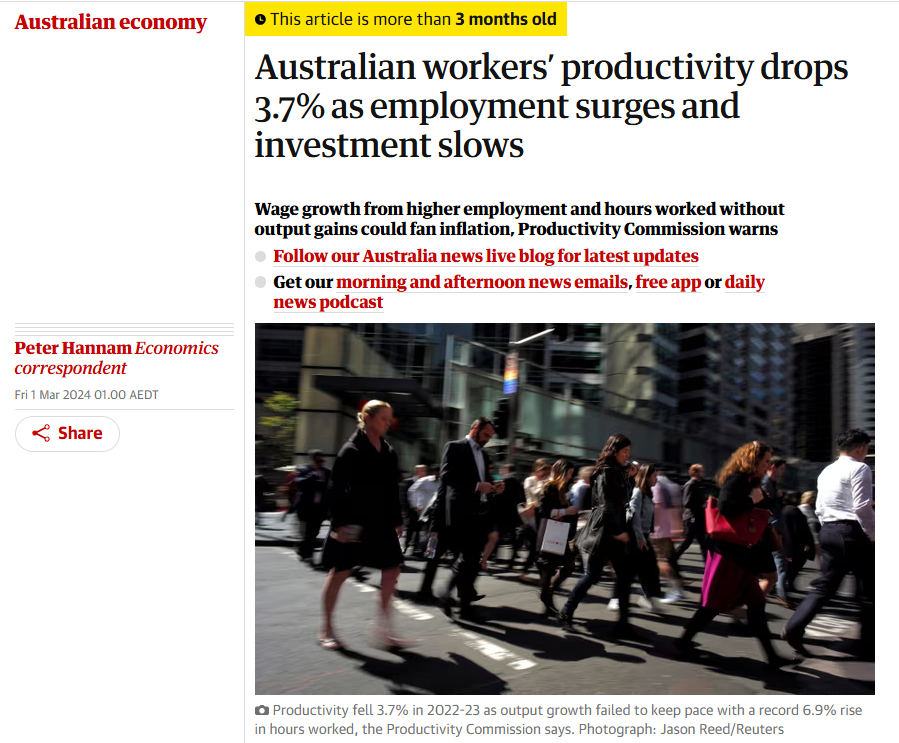

Earlier this year, Australia’s media, the Productivity Commission, and business lobby groups ran the argument that Australia’s low labour productivity would prevent the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) from cutting interest rates.

“A surge in employment combined with scant investment by firms to improve output triggered a sharp drop in worker productivity, limiting prospects for income growth without fanning inflation, the Productivity Commission said in its annual report”, the above article read.

“Employers, though, were also not doing their bit. The capital-to-labour ratio, one measure of spending on equipment to improve output, fell by a record 4.9% for the year”.

“So while a record number of Australians had jobs, employers didn’t invest in the equipment, tools and resources that are needed to make the most of employees’ skills and talents”, Productivity Commission deputy chair Alex Robson Robson said.

“Further capital investment would help turn our strong employment growth into strong productivity growth”.

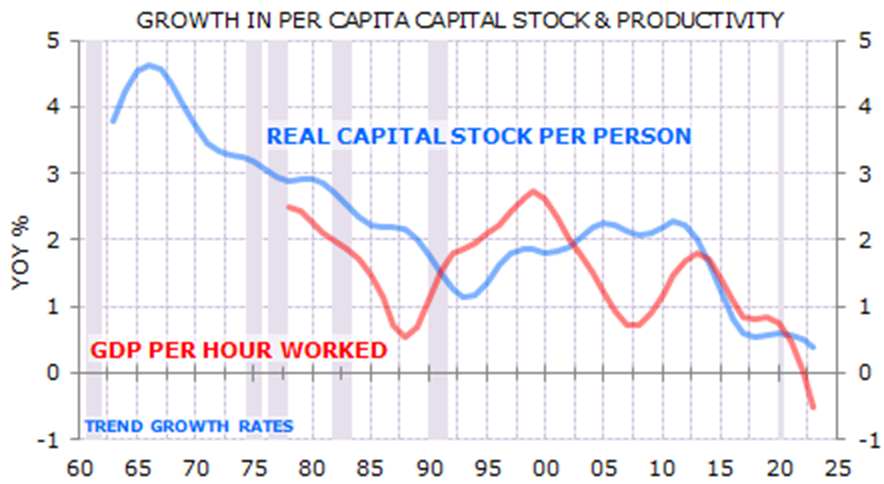

The Productivity Commission was right to blame Australia’s poor productivity on capital shallowing, which happens when a nation’s population grows faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment, resulting in less capital per person.

Two decades of excessive population growth via strong immigration have indeed delivered capital shallowing in Australia and lowered productivity growth:

Where the Productivity Commission is misguided is the notion that lower labour productivity growth means higher interest rates.

This view was comprehensively debunked by the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) decision on Wednesday to commence a monetary easing cycle.

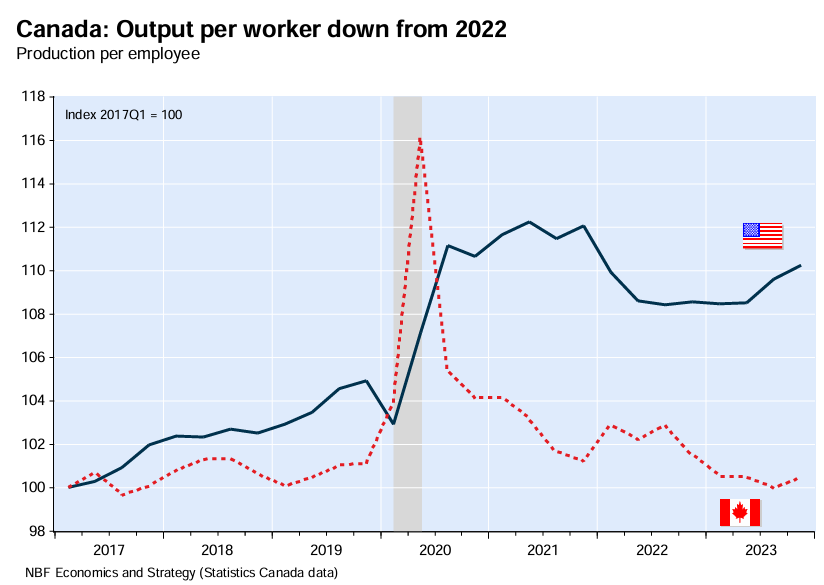

Like Australia, Canada’s labour productivity has collapsed amid record immigration-driven population growth, which has shallowed the nation’s capital base:

The comparison with productivity in the United States is stark.

Canada’s output per worker has been falling, whereas it has boomed in the United States:

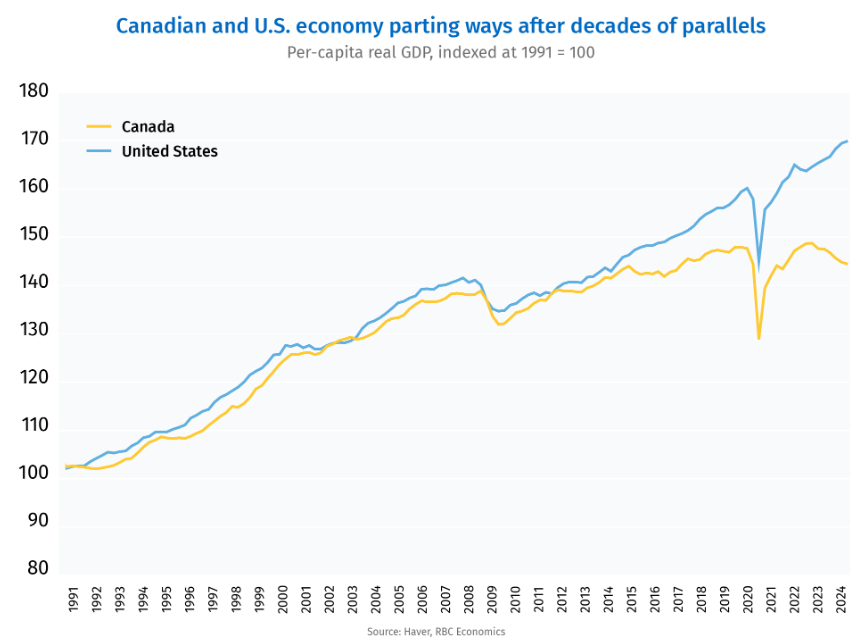

In turn, Canada’s real per capita GDP has collapsed, whereas it has risen significantly in the United States:

If poor productivity growth was a legitimate concern with respect to rate cuts, then the BoC would not have cut rates.

When an economy is driven by labour supply growth via mass immigration, as is the case in Canada and Australia, productivity and wage growth tend to fall together.

The falling capital stock per person ensures that economic activity becomes less efficient over time, requiring more labour for the same amount of output.

The next phase of the cycle will involve a simultaneous decline in productivity and wages. Inflation will disappear as idle labour piles up, lifting unemployment.

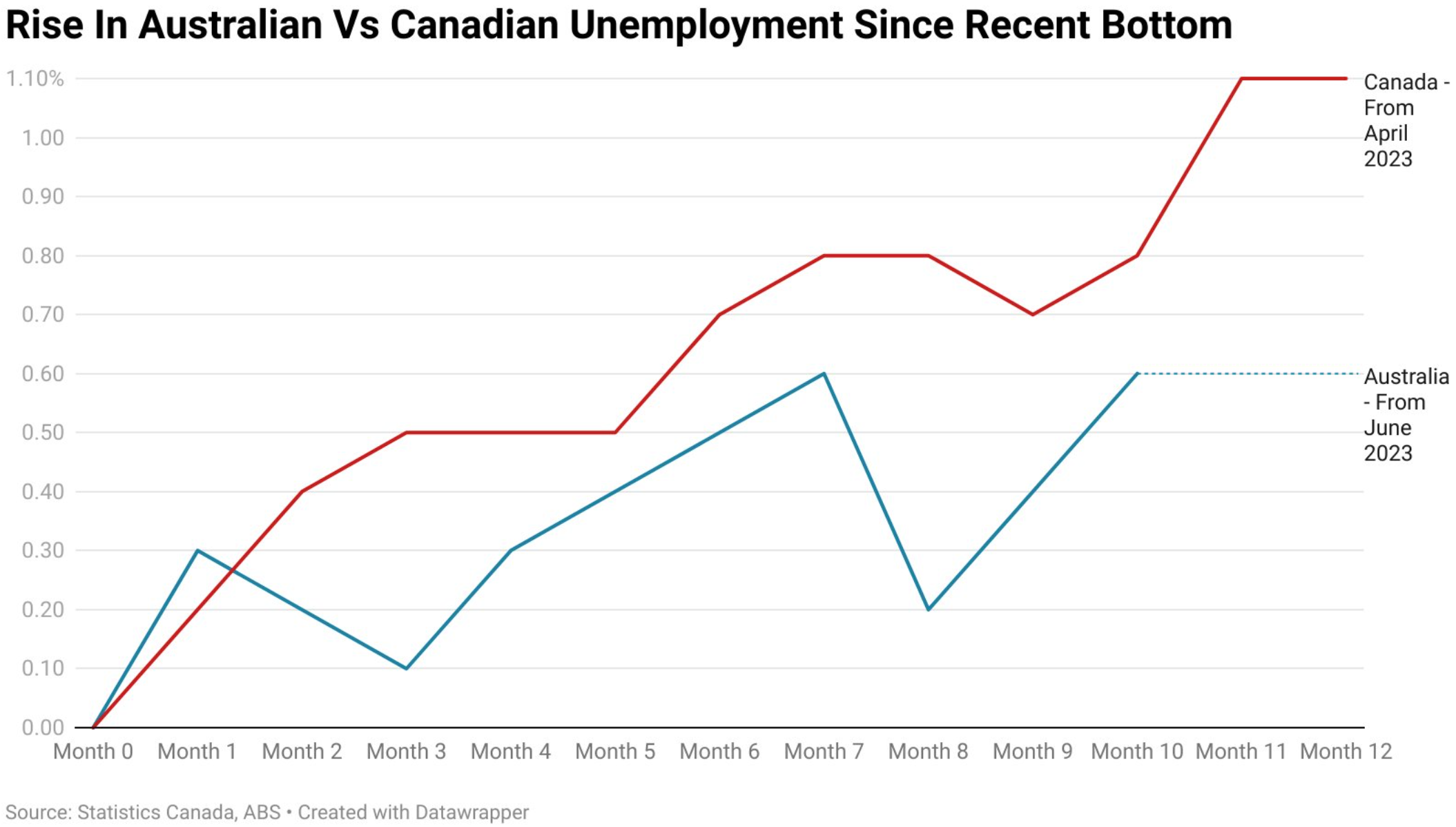

The BoC’s rate cuts are the first salvo in this process. The RBA will follow in due course. But first, the RBA needs to see a significant rise in unemployment and/or falling inflation.

Source: Tarric Brooker