The rate hike blame game – RBA vs Albo

Following the resumption of rate rises from the RBA earlier this week, many Australians have been left wondering how things went so badly wrong that the RBA has needed to raise rates only a year after it started cutting them, despite the prior rate rise cycle delivering the largest relative rise in mortgage rates in Australian history.

The Albanese government would love to blame the RBA for failing to manage inflation. But realistically, they could only have raised rates earlier.

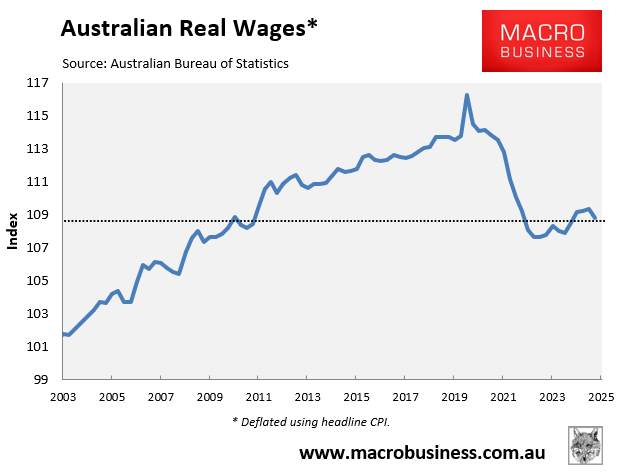

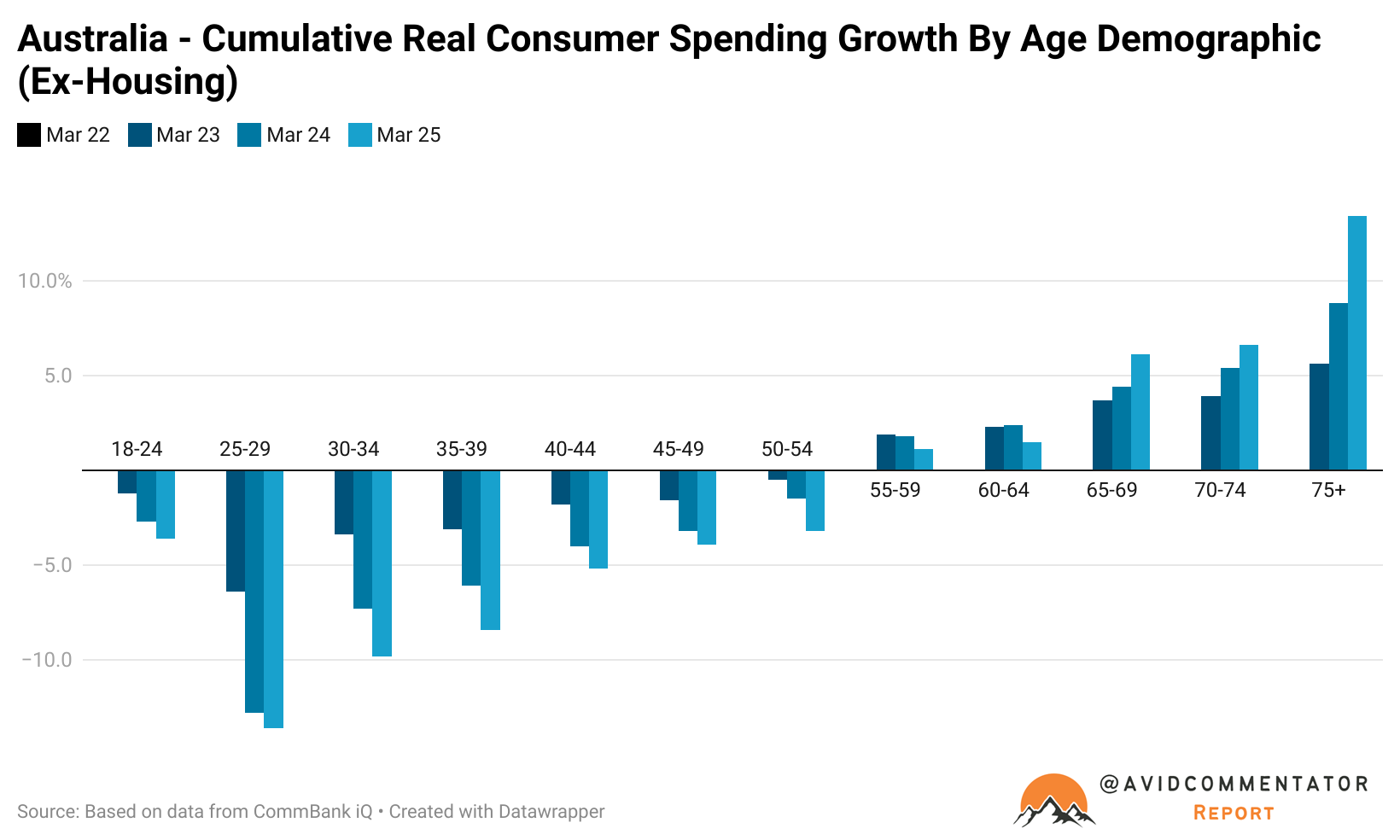

The simple reality is that a combination of inflation and declining real wages has led to declines in real spending among the majority of households.

According to figures based on data from Commbank IQ, real per capita consumer spending (ex-housing) has fallen across every age demographic under the age of 55, with 25- to 29-year-olds experiencing a technical depression in their spending on this metric.

So if spending has been smashed, how is it that Australia has such a significant inflation problem?

In summary, the issue stems from a large, poorly targeted immigration intake and an expansive growth in government spending.

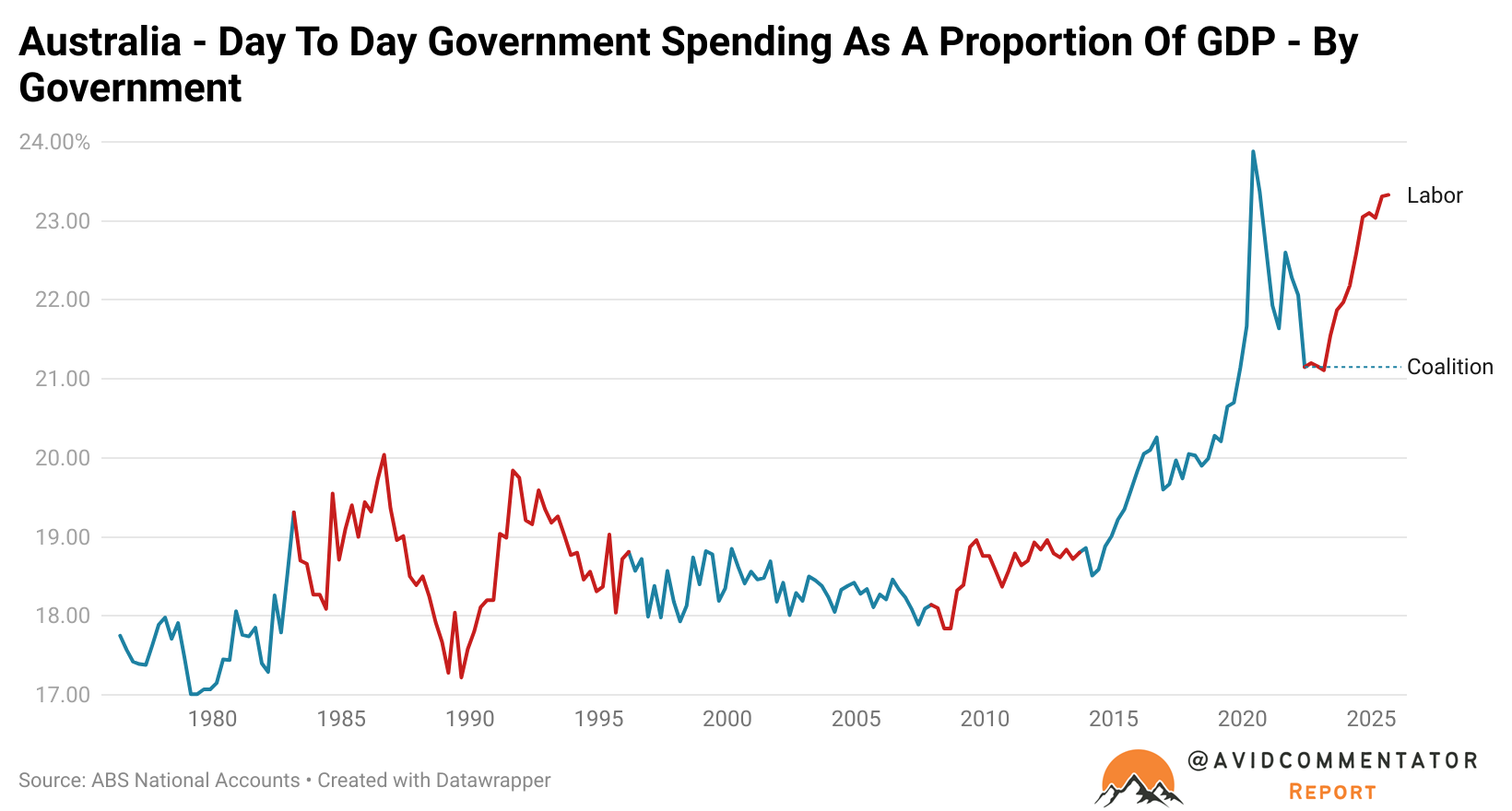

As of the latest national accounts data, day-to-day government spending as a proportion of GDP is currently at its third-highest level on record, with only the two most pandemic-impacted snapshots producing a higher figure.

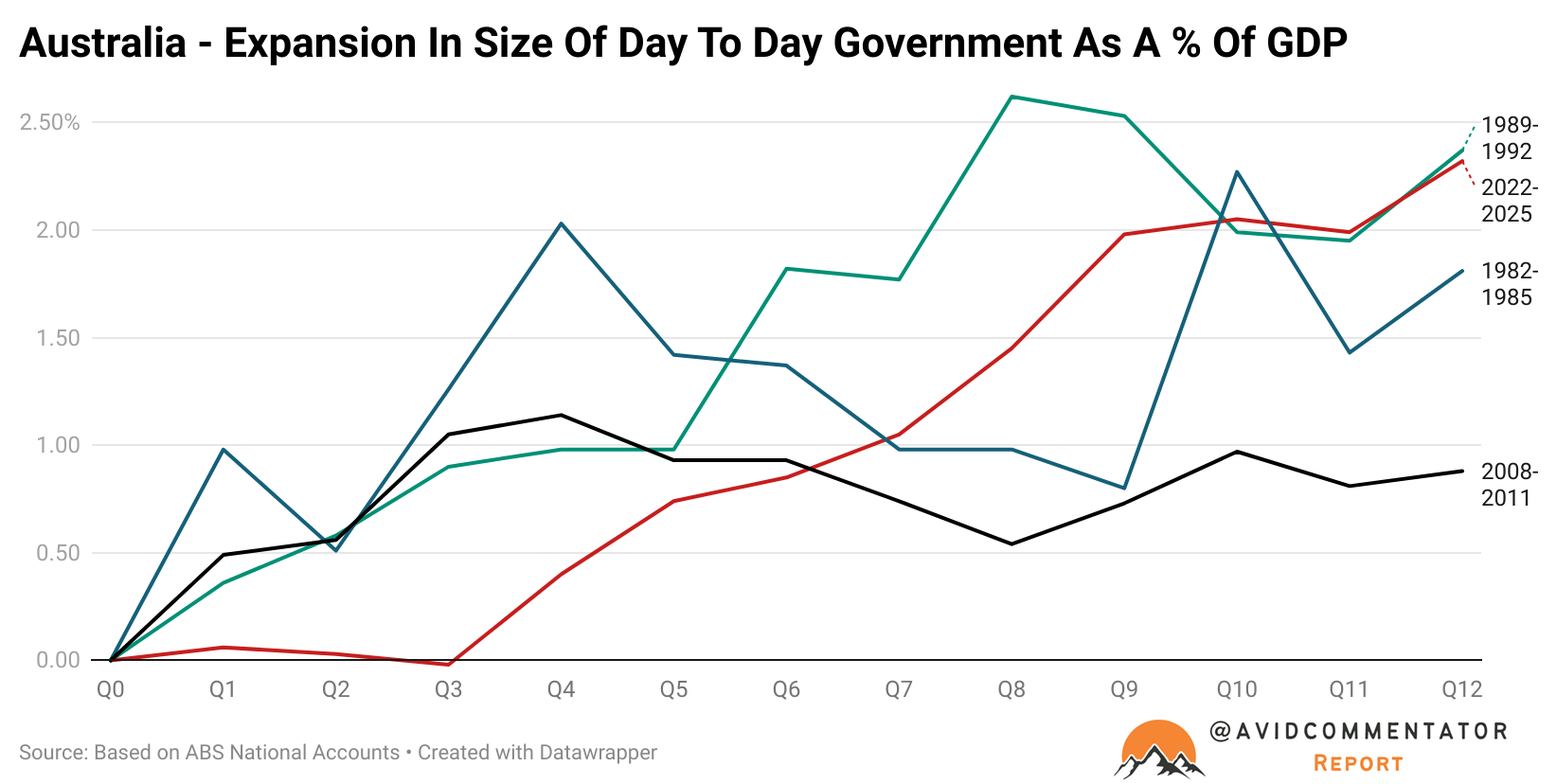

The growth in the size of day-to-day government as a proportion of GDP under the Albanese government bears a greater resemblance to government actions during a recession than to normal business operations.

In fact, across the last 40 years of data, there is only one other instance where day-to-day government spending has expanded more as a proportion of GDP; that was during and following the 1990-1991 recession.

Meanwhile, the nation’s large and poorly targeted migration intake has delivered conditions consistent with a deterioration in the productivity growth potential of the Australian economy, making the fight against inflation harder, not easier.

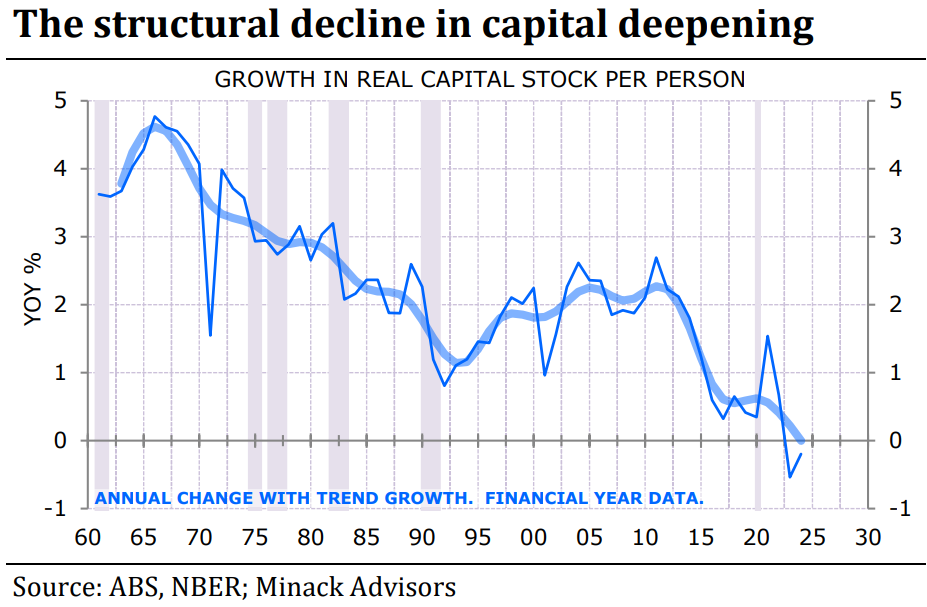

According to an analysis from Minack Advisors, the growth in real capital stock per person has fallen into negative territory.

Capital stock from the perspective of a national economy is the total value of various assets, such as infrastructure, equipment, intellectual property, or factories used in the production of goods and services.

This is a key input into productivity growth, which plays an instrumental role in defining what level of growth in the economy can occur without it being inflationary.

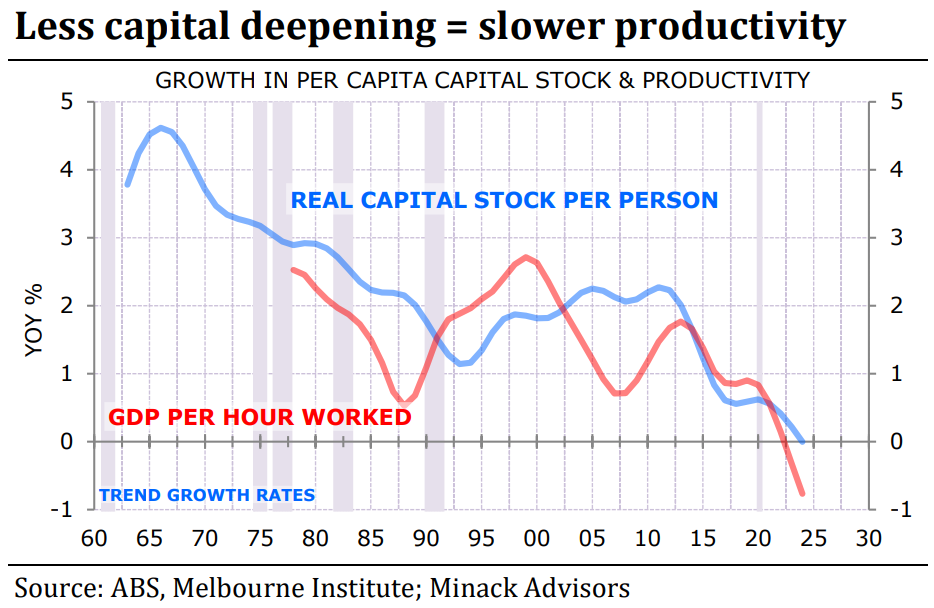

As the chart below from Minack Advisors illustrates, as real capital stock per person has fallen, so too has productivity growth over the last decade.

There is also the issue of the most basic form of economics.

If you are expanding the base of consumers (demand) without facilitating an expansion in the means of delivering goods and services (supply), you are creating an inherently inflationary scenario.

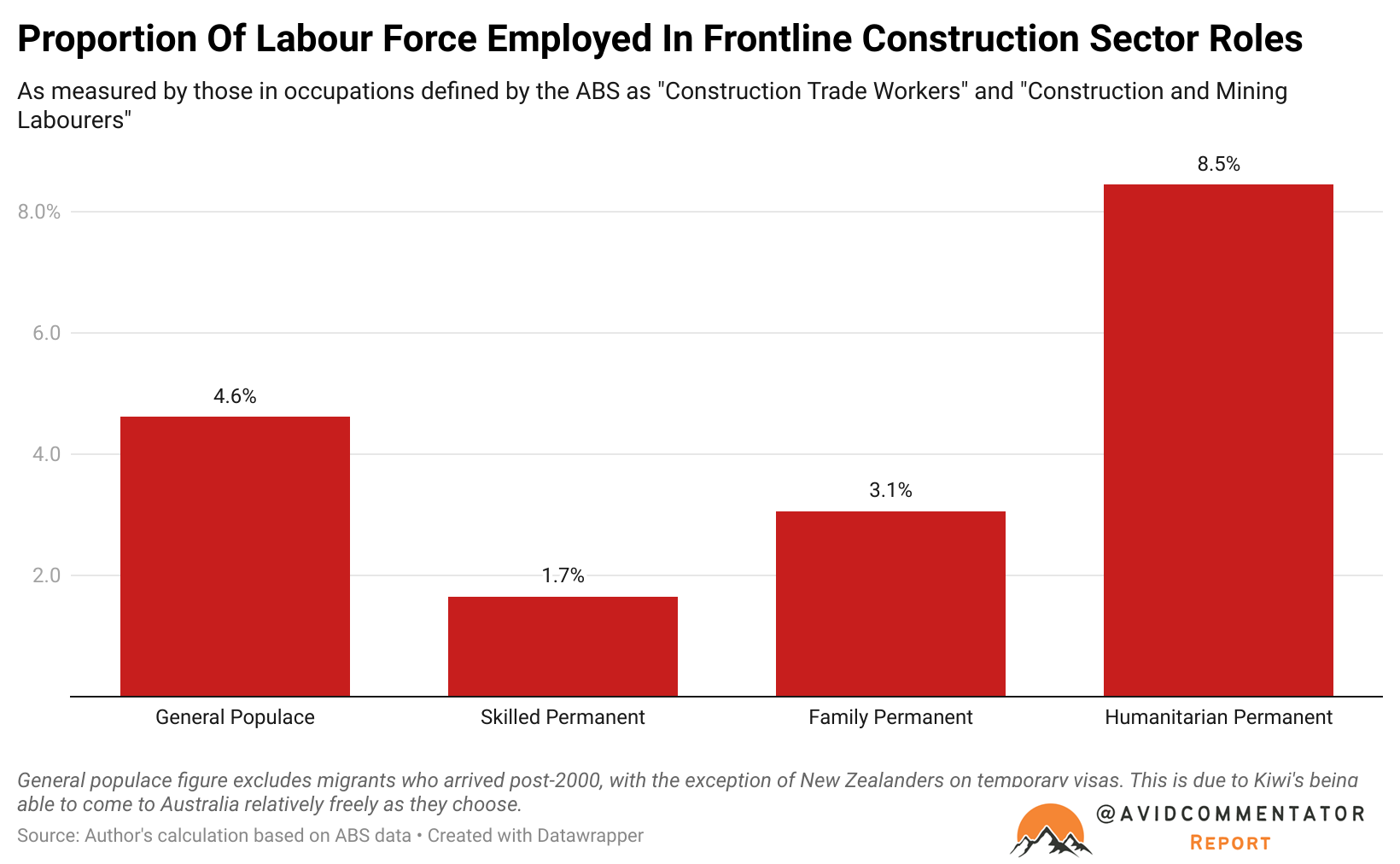

A good illustration of this is the construction sector.

Migration adds significantly more demand for homes, renovations, and home maintenance than it does supply.

The Takeaway

While the RBA should have arguably pushed back significantly harder against the inflationary policies of the government, the reality is that, given their relative capabilities, the only thing that would have realistically been different is that rates would have risen sooner.

They ultimately have one blunt tool, monetary policy, so effectively they have a hammer so every problem has to be a nail.

Conversely, the Albanese government, in collaboration with certain state governments, has created favourable conditions for inflation to persist and experience a resurgence.

From a political perspective, their strategy has worked marvelously; they have won a massive majority, and their major party opposition is in absolute disarray.

However, from the perspective of the average Australian on the street, it has resulted in recession-like conditions without a rise in unemployment, creating a situation where real wages and real household spending (excluding housing) could take over a decade to recover.