Why China is in deep trouble in one chart

In 2012, the Gillard government declared that the 21st century would be the “Asian Century”, and produced a White Paper detailing its expectations for how things would play out, entitled “Australia in the Asian Century”.

It included expectations such as a baseline scenario predicting China would grow at 7% each year from 2012 to 2025, with even the downside scenario anticipating a still extremely robust growth rate of 6.5%.

In reality, just 15 months after the release of the Gillard government’s White Paper, China recorded 7% growth for a calendar year for the final time.

Meanwhile, 2018 would represent the final calendar year that even the downside scenario of 6.5% would be realised.

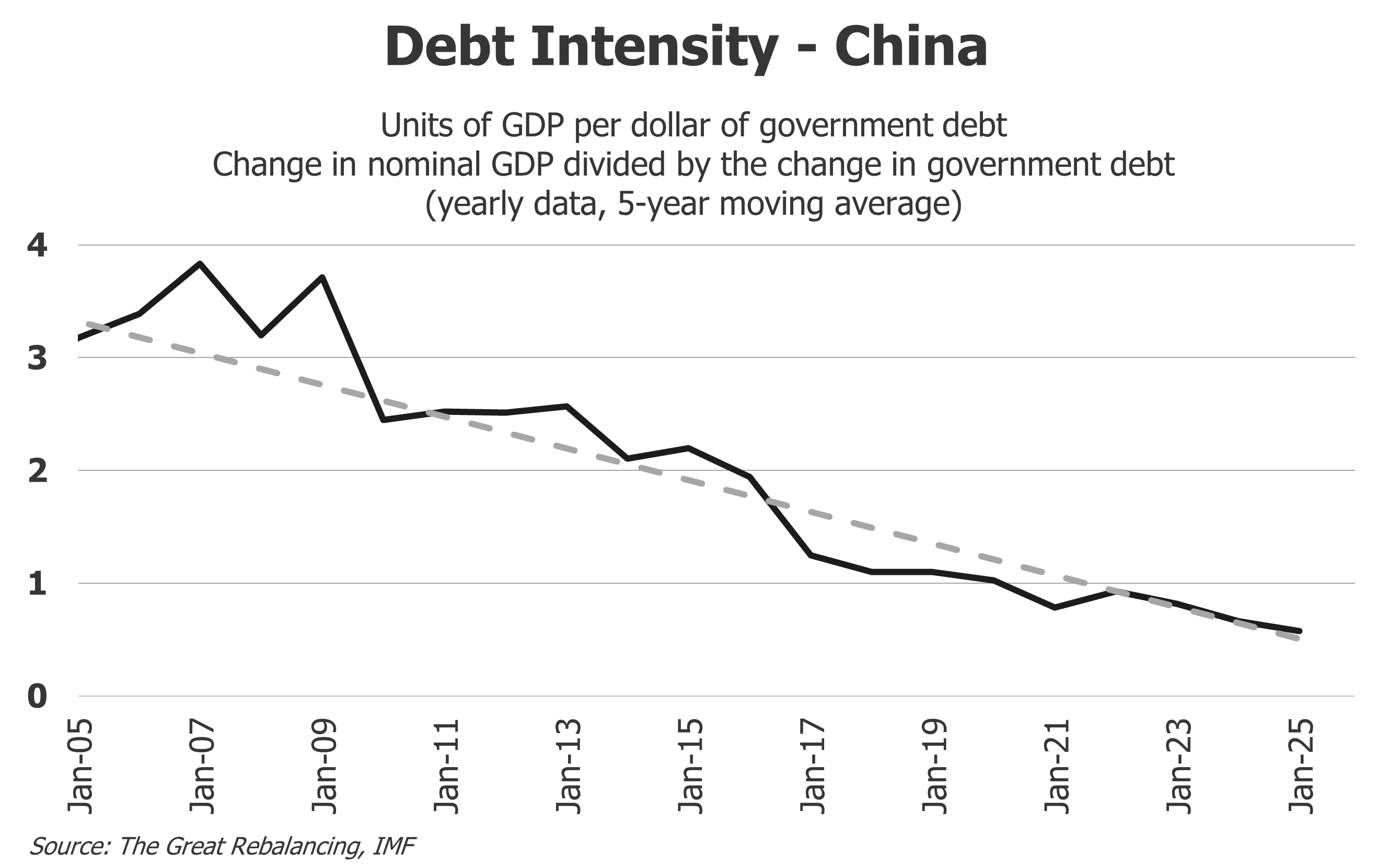

This brings us to today’s key chart.

On a rolling 5-year average, in 2006, each additional dollar of government debt delivered China 3.8 dollars of additional GDP.

By mid-2020, this metric reached a critical point at which an additional dollar of government debt no longer yielded an additional dollar of GDP.

Over the following years, it would continue to trend down, until today, when each additional dollar of government debt delivers around 60 cents of additional GDP.

Source: Jeroen Blokland

In short, what is happening in China is that government investment is increasingly directed toward projects with an inadequate business case, resulting in significantly less additional economic output than back in the days when it was directed at genuinely productivity-enhancing projects.

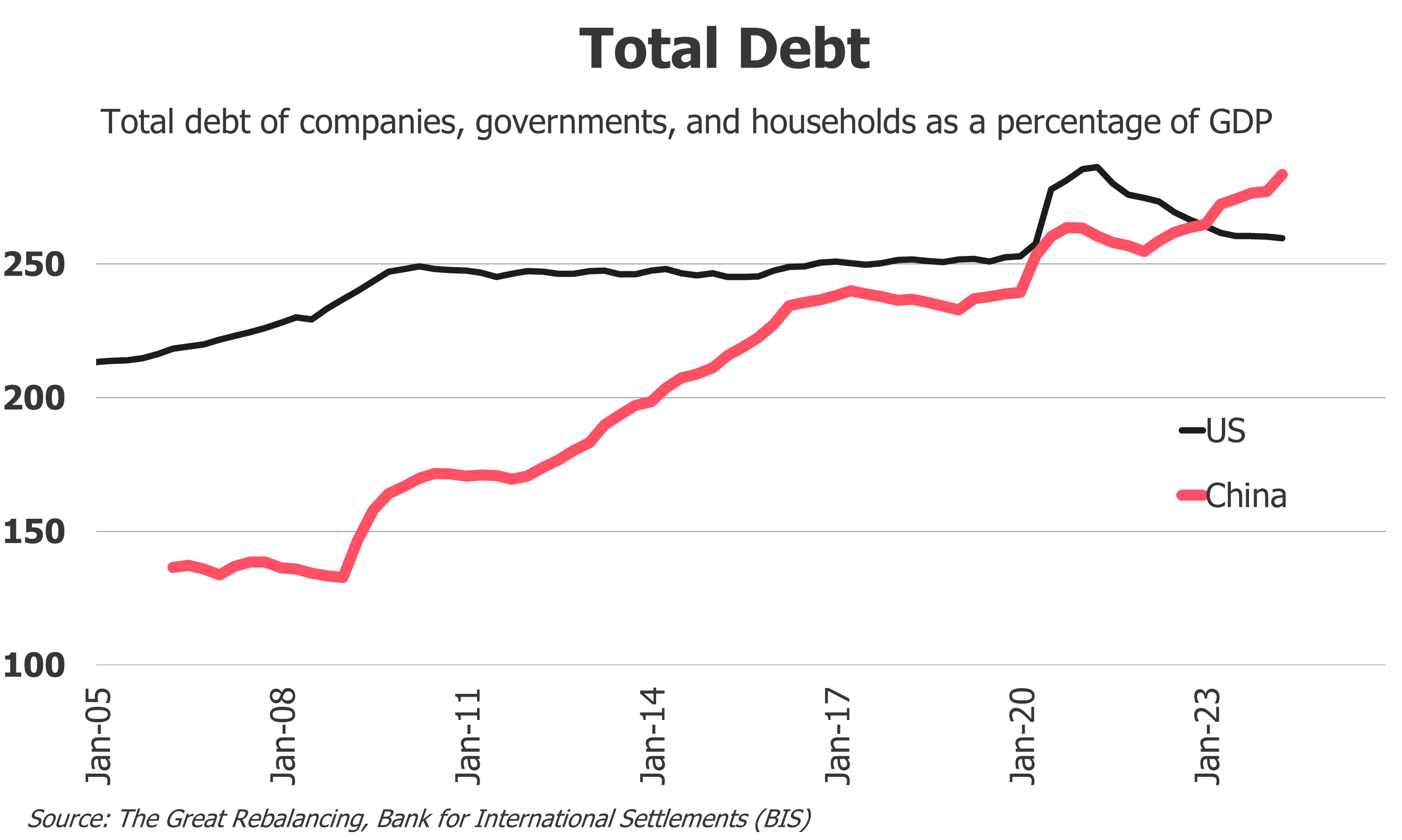

While there have long been concerns about the total level of American debt, which are admittedly entirely justified, China’s total debt-to-GDP ratio surpassed that of the United States in early 2023, and this divergence has continued to grow.

Source: Jeroen Blokland

This leaves Australia in an increasingly challenging position, reliant on Beijing continuing a strategy that has been delivering ever greater levels of diminishing returns.

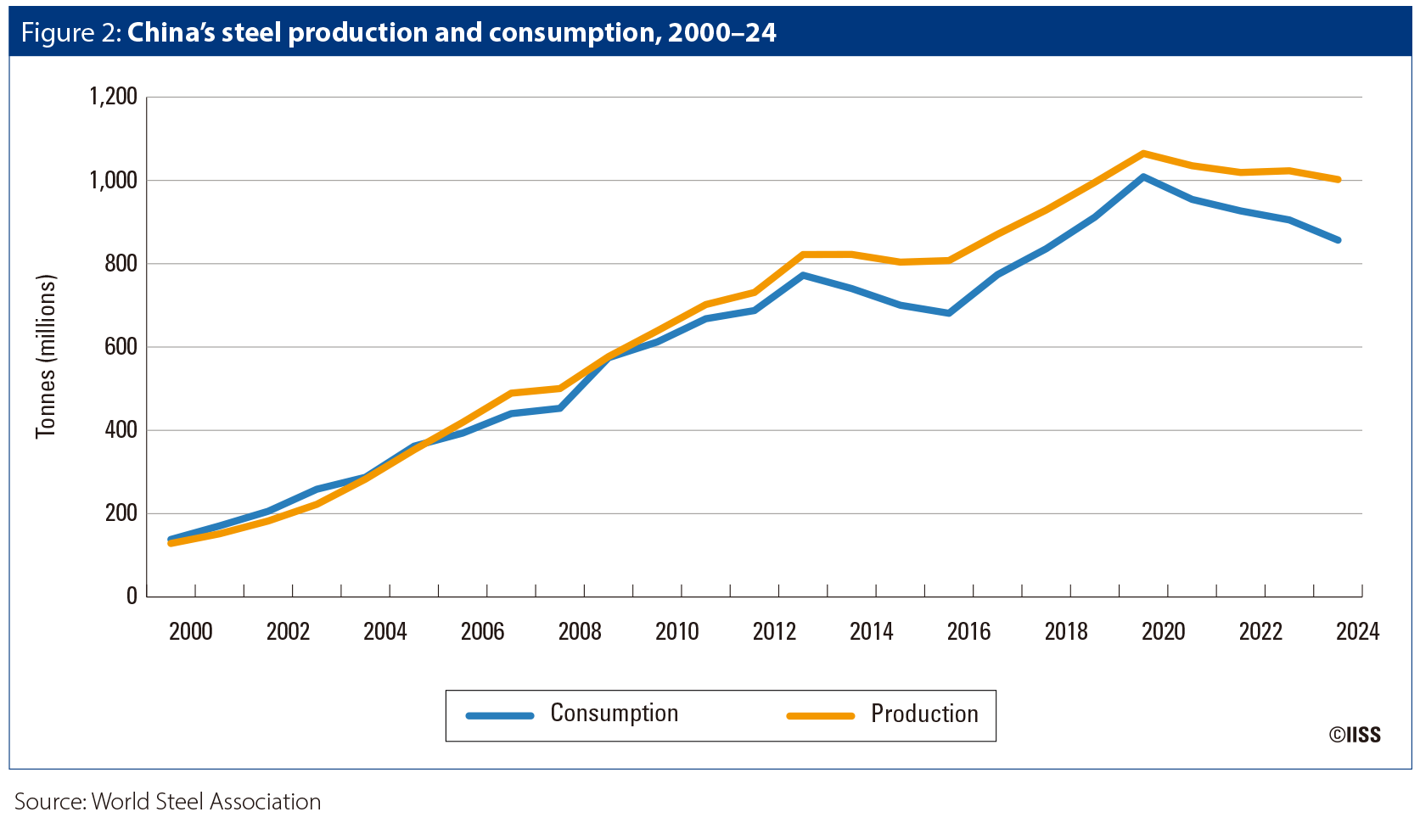

Unlike the Gillard government’s view of the future, which would see China boom across the range of forward estimates, the reality is key indicators for Australia, such as Chinese steel production, peaked in 2020 and have never fully recovered.

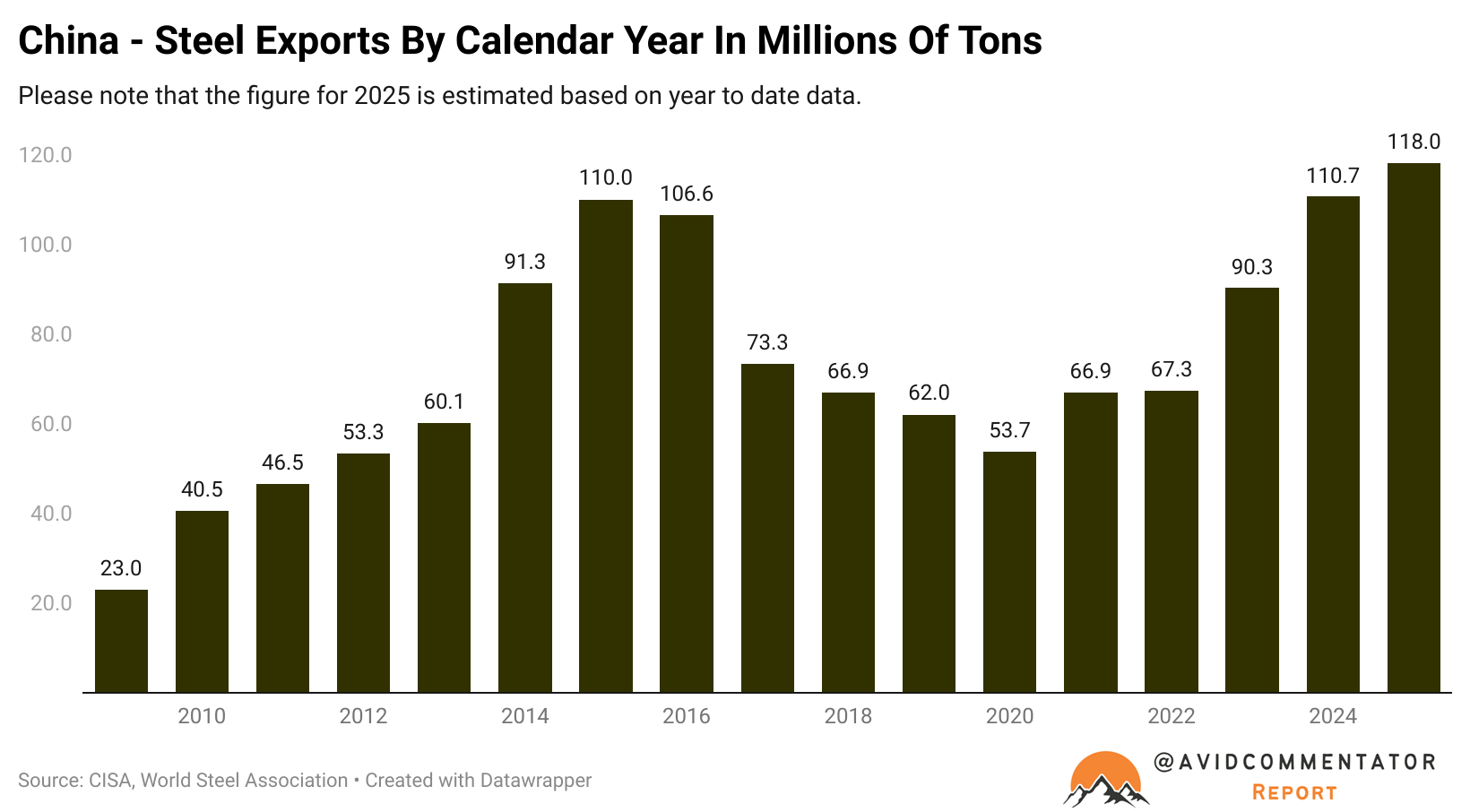

Instead, China, and by extension Australia, has become increasingly reliant on exports of steel to other nations.

It’s entirely possible and some would argue likely, that China will return to its old ways of steel-intensive, infrastructure construction-fueled growth as it struggles to evolve into a more consumer- and services-focused economy.

But as today’s key chart illustrates, that comes with a reality of deeply diminished returns and an ever greater load of debt relative to economic output left to pay for it.

Ultimately, the choices of Chinese policymakers on the road ahead will prove defining for not only the Middle Kingdom but also its most symbiotic non-Asian trading partner, Australia.