Australia’s doors to be opened by treaty to 450m people?

Since 2018, the Australian government has been attempting to negotiate what is one of the toughest and most time-consuming diplomatic agreements in the world: a free trade agreement with the European Union (EU).

In that time, there have been several major sticking points for the two sides, from the acceptable volume of Australian meat and dairy flowing into the EU to Australia respecting restrictions imposed on the names of various products that relate to specific regions, such as feta or prosecco

In an attempt to get the agreement across the line, EU negotiators have added an additional element to the deal: a migration pact.

Under the proposed deal, EU citizens would be able to live and work freely in Australia for up to four years without needing to secure a job in advance, with the possibility of permanent settlement options.

The agreement would be entirely reciprocal, with Australians gaining the same rights to live and work within the EU.

The latest reports from Canberra suggest that the provision is under consideration by the Albanese government, with sources within the government stating that it would help fill labour gaps by attracting workers trained to similar standards, such as builders.

On paper and in a vacuum, admitting tradies from European countries with similar standards is a solid idea.

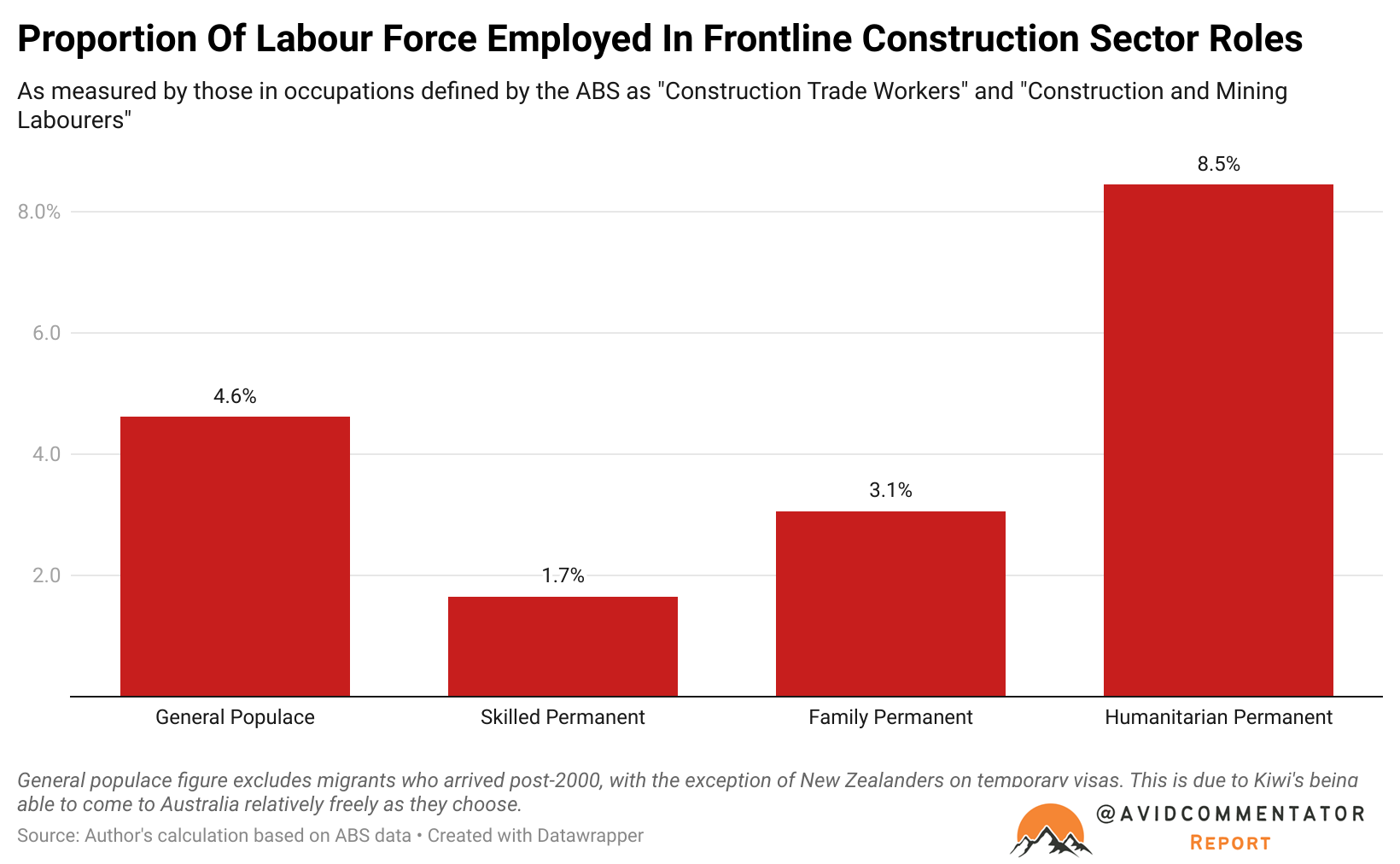

After all, just 1.7% of the permanent intake of migrants chosen for their skills (post-2000) end up working in frontline construction sector roles, compared with 4.6% of the broader non-permanent migrant populace.

The problem is the sheer numbers involved in any agreement.

If an agreement were signed without a cap, it would open Australia’s doors for up to 450 million people, an order of magnitude more than the 27.8 million people who call Australia home.

There is also the potential issue of healthcare.

Australia currently has reciprocal healthcare agreements with 9 EU nations (Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and Sweden). These agreements entitle individuals from these nations to medically necessary care, but not for injuries and illnesses that can wait until an individual returns home.

Given that the admissions timeline is up to four years, would this effectively provide access to substantial elements of Medicare at the Australian taxpayer’s expense, in all but name, for citizens of these nations?

The Takeaway

Over the last decade, successive governments in Canberra have entrenched increasing levels of migration through treaties with other nations.

From British working holiday makers to Indian yoga instructors, successive governments from both of the major parties have committed to Australia taking more migrants.

If even 0.01% of the EU population saw an opportunity in a move to Australia each year, that would be 45,000 additional migrants.

That is one of the major risks of pursuing such an agreement, particularly with a bloc whose population is more than 16 times that of Australia.

While that would be somewhat offset by Australians heading the other way, the EU is so much larger that even half as many people taking up the offer per capita would still see a completely unbalanced set of flows.