In a recent article for the Australian Financial Review, economist Christopher Joye made the case that the expansion of government at all levels was putting upward pressure on inflation and, by extension, interest rates.

“At the federal level, the annualised monthly trend budget deficit has deteriorated rapidly from $12 billion in December 2024 to $24 billion in June 2025 and now $35 billion in November”.

“This deficit represents the shortfall between public revenues and spending. And it does not account for spending at the state and local government levels”.

“If we sum up the gargantuan deficits being produced at all levels of government, the total consolidated loss will balloon to about $88 billion this financial year”, Joye wrote.

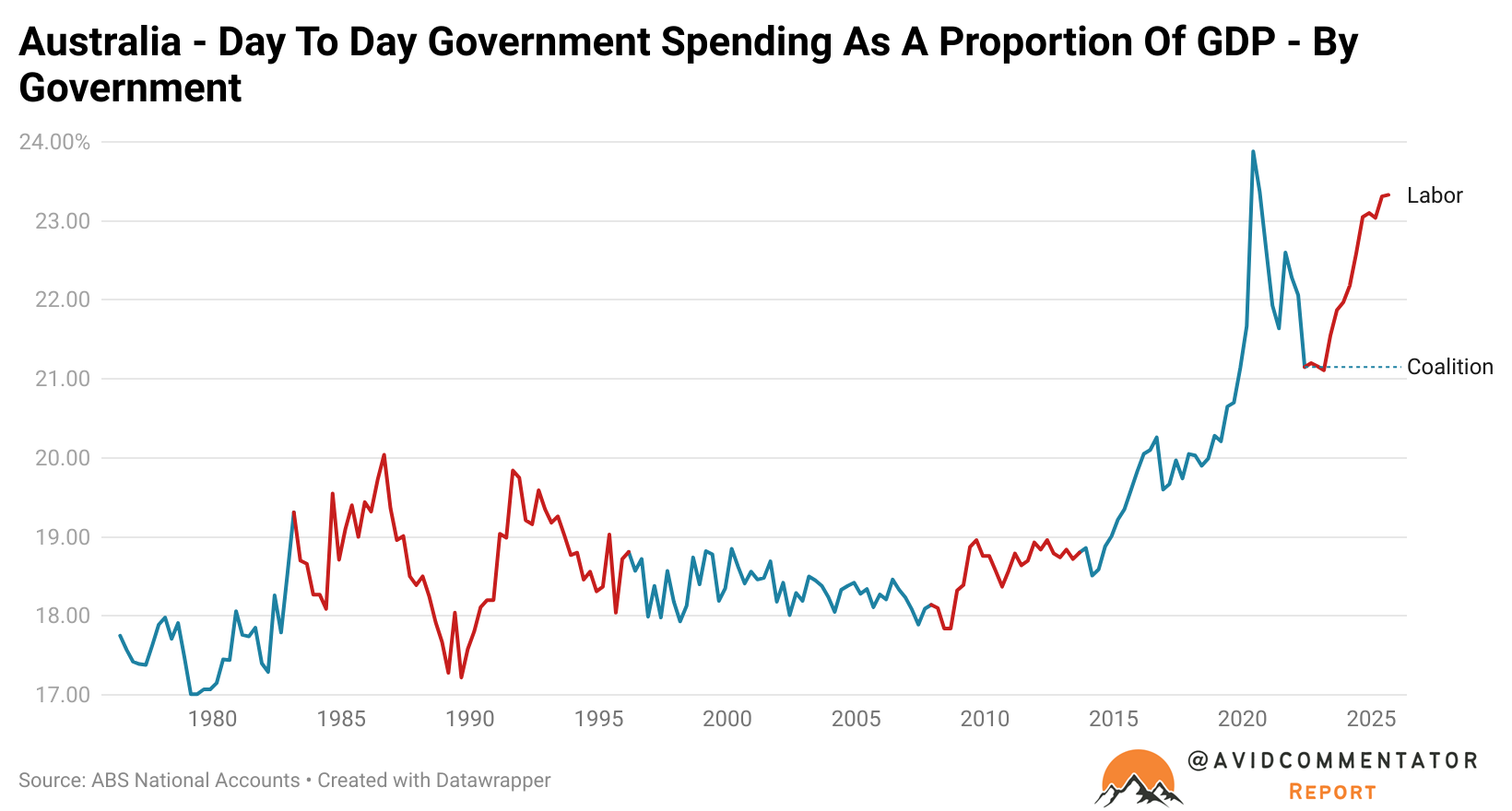

Looking at the relative size of government over time, it’s clear that Joye has a point.

The latest national accounts data showed that day-to-day government spending as a share of GDP has reached its third-highest level on record.

The only two data points that exceed the current relative size of government are from the June and September quarters of 2020, which occurred during the height of the pandemic.

To be completely fair to the Albanese government and its counterparts in state and local government, this is not a new thing.

Since the mid-2010’s government has gotten larger and larger, playing a pivotal role in keeping a largely anaemic economy afloat during the latter half of that decade.

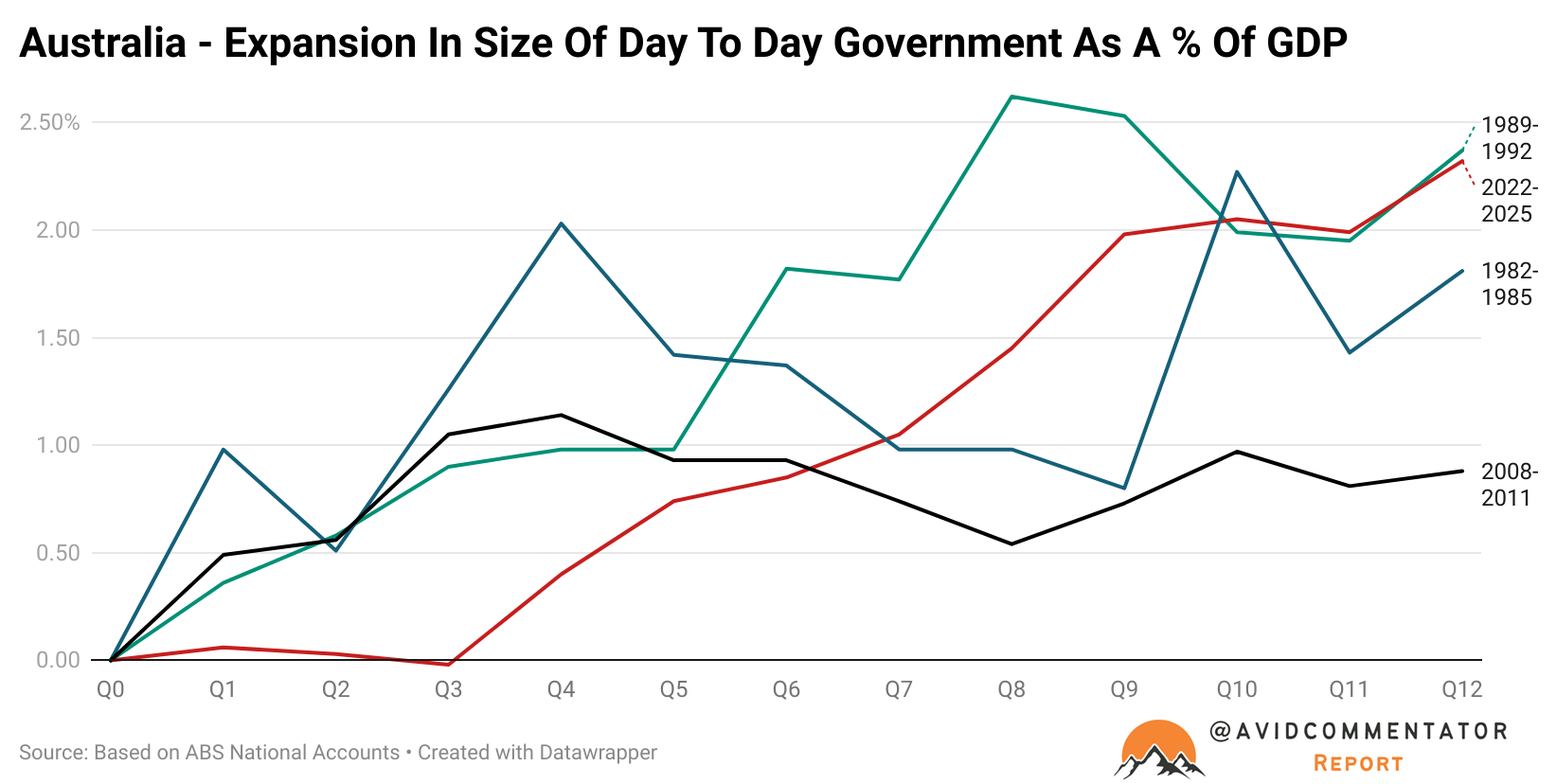

However, the rise seen during the era of the Albanese government has been meteoric and closely mirrors the relative expansion in the size of government seen during the 1990-1991 recession, and its immediate aftermath.

What we have seen is a crisis level expansion of government as a proportion of GDP, despite conditions being ostensibly normal.

But as Joye writes in the AFR this has significant consequences.

“If we want to avoid interest rate hikes, we need to dramatically pare back public spending. We need to back our people rather than our politicians to power prosperity in an extraordinarily competitive world.”

“Today we are trading away whatever remaining edge we have left, forcing the nation to rely on selling its natural resources and physical amenities. We are turning into Asia’s Ibiza”, Joy wrote.

Balancing It Out

While Joye is correct in his diagnosis and prescription, it is not a course of treatment without risk.

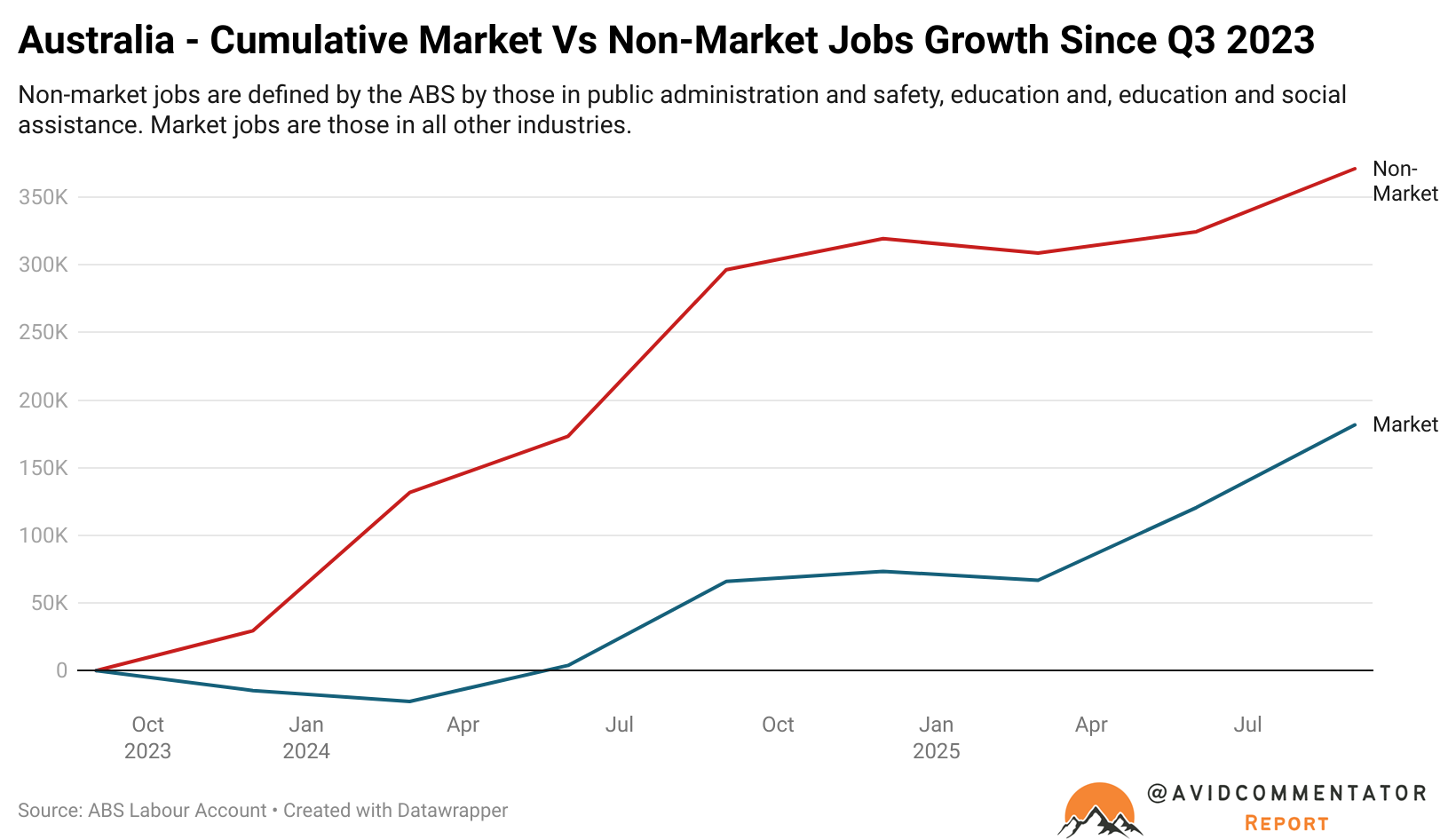

For better or worse the economy has become deeply reliant on taxpayer-funded employment growth over time and without the government boosting the economy’s fortunes with money printed through deficits, the likelihood of a recession rises dramatically.

That may be an acceptable outcome for many Australians, who are already facing recession-like conditions in their living standards and their scope for social mobility.

But for the Albanese government, which has already expended a significant amount of money on intervention to support the economy, both directly and indirectly, it represents a major risk to their future political fortunes.

It’s for this reason, amongst others, that some variation of the status quo will continue, even though few Australians benefit outside of government.