China gobbles up global export market

As battles over trade flows and domestic industry intensify worldwide, it’s worth stepping back and reflecting on how this set of circumstances has come to pass.

According to an analysis from the Wall Street Journal, the total inflation-adjusted volume of Chinese exports has risen by 44% since 2019.

Meanwhile, China’s imports have risen by only 1% during that period.

Based on a very rough estimate of global manufactured goods trade flows, the total inflation-adjusted volume of global manufactured goods flowing around the world has only risen by around 11%.

In short, China is growing its market share at the expense of its foreign competitors, as it attempts to keep its economic growth robust in the face of traditional engines such as the property and infrastructure construction sectors falling into contraction.

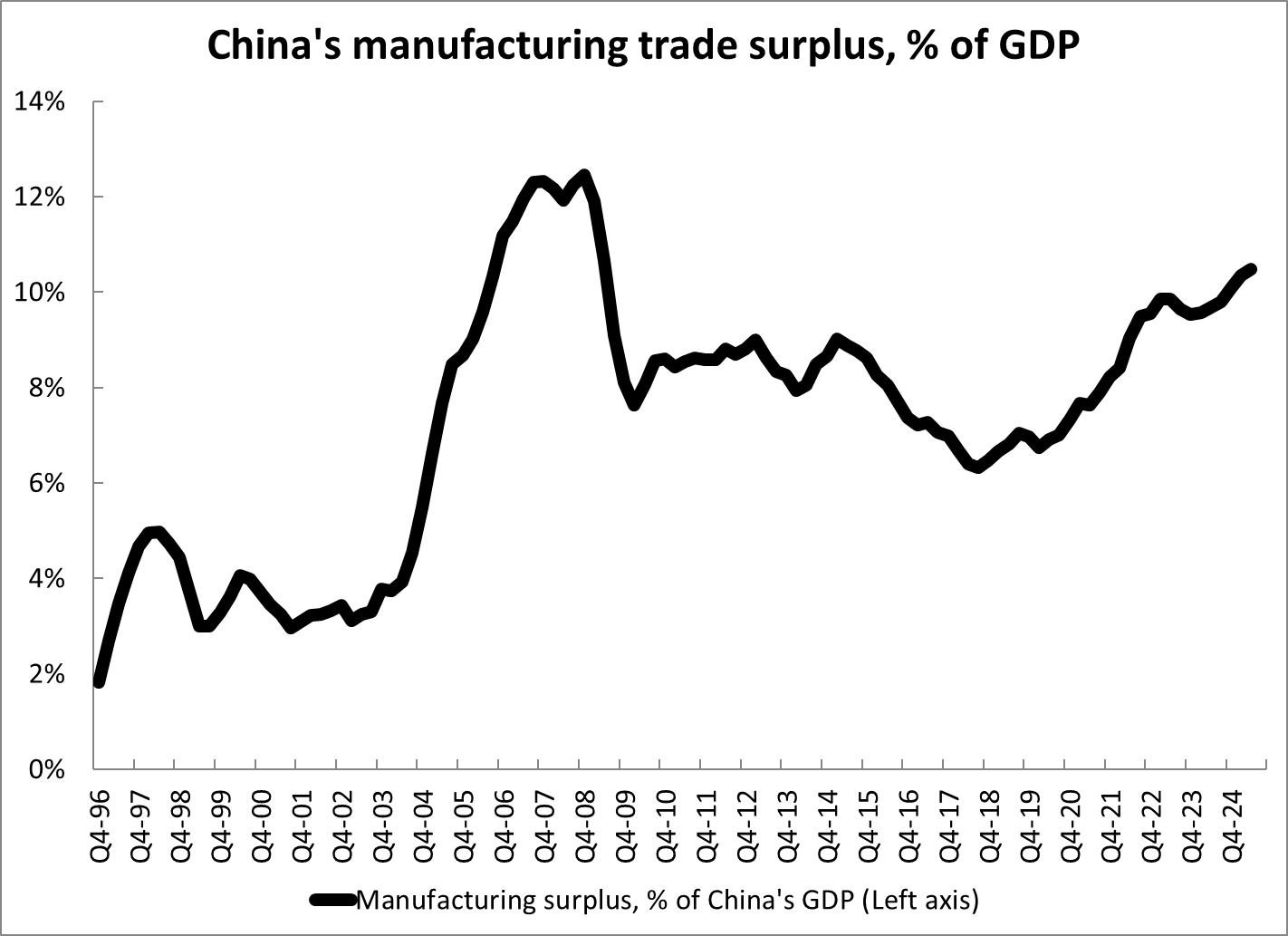

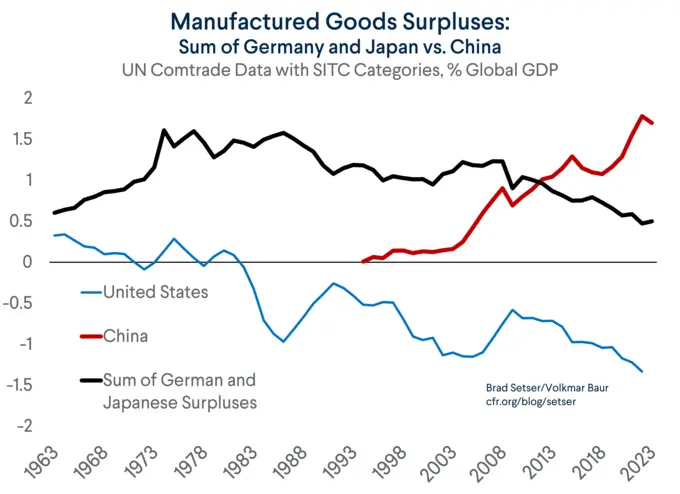

Examining global manufactured goods flows through the lens of global GDP reveals a fascinating and concerning trend.

The Chinese trade surplus in manufactured goods, as a proportion of global GDP, is larger today than the combined surpluses of Germany and Japan at their peak in the early 1970s.

To sum it up in a single sentence, China is the most trade-dependent nation in the history of the modern industrialised world.

While it is definitively the world’s factory, and the overwhelming majority of nations throughout the world are reliant on China for everything from pharmaceuticals to rare earths, Beijing is equally reliant on global trade continuing to flow.

As the chart above from the Council on Foreign Relations illustrates, China has developed a deeply symbiotic relationship with the United States when it comes to trade flows.

Where China holds the honour of the largest manufacturing trade surplus in the history of the modern industrialised world, the United States holds the title of the largest manufacturing trade deficit.

As the U.S. increasingly looks to bring manufacturing back to North America or to allied nations, particularly in Asia, China needs to find somewhere to sell its increasingly large amount of manufactured exports.

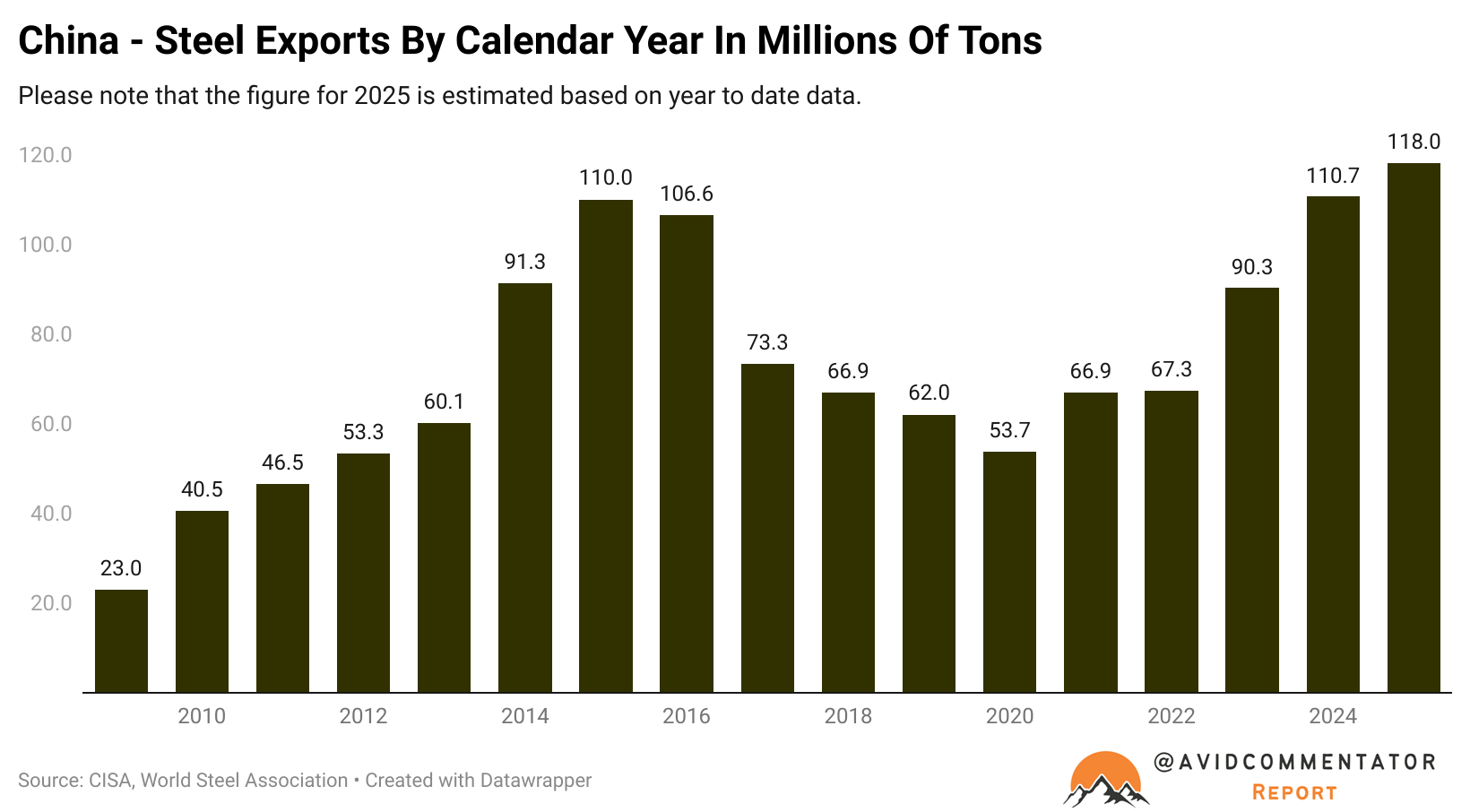

A notable Australia-related example of this is Chinese steel.

With domestic Chinese steel consumption now falling significantly and potentially irrevocably, the Middle Kingdom’s steel mills are being forced to look overseas to find a home for their wares.

Currently, Chinese steel exports are on track for another record high year in 2025, with roughly 118 million tons expected to be exported this year.

This would render China’s steel export sector by itself as the third largest producer of steel in the world.

While Chinese steel is generally cheaper than its competitors, it often comes with a long-term cost many nations are increasingly unwilling to pay: the atrophy and potential death of domestic steelmaking.

It is this type of threat to more advanced manufacturing capacity that is seeing nations push back against Beijing’s attempts to find a home for its manufactured goods in their markets.

A recent example of this was a statement from French President Emmanuel Macron, who warned the European Union may be forced to take what he describes as “strong measures” against China, which include potential tariffs and other trade barriers if Beijing fails to address its growing trade surplus with the EU.

“I’m trying to explain to the Chinese that their trade surplus isn’t sustainable because they’re killing their own clients, notably by importing hardly anything from us any more”.

“If they don’t react, in the coming months we Europeans will be obliged to take strong measures and decouple, like the US, like for example tariffs on Chinese products”, Macron said

Ultimately, China and much of the industrialised world are on what appears to be an unavoidable collision course when it comes to trade; the big question is how messy will the battle become?