In the last four years, expectations for the RBA cash rate have been wildly variable.

Back in late 2021, the Commonwealth Bank was projecting a peak cash rate of just 1.25% by the end of 2023.

While this estimate may seem low now, it was not alone at the time, as many economists and institutions held a similar view that the cash rate would end up in a similar range.

In reality, the cash rate reached 4.35% by the end of 2023, signaling the conclusion of the largest and fastest relative tightening cycle in the nation’s history.

Now, it is increasingly expected that the path of the cash rate may once again confound previous expectations, as market pricing turns more strongly toward the possibility of rate hikes in the coming new year.

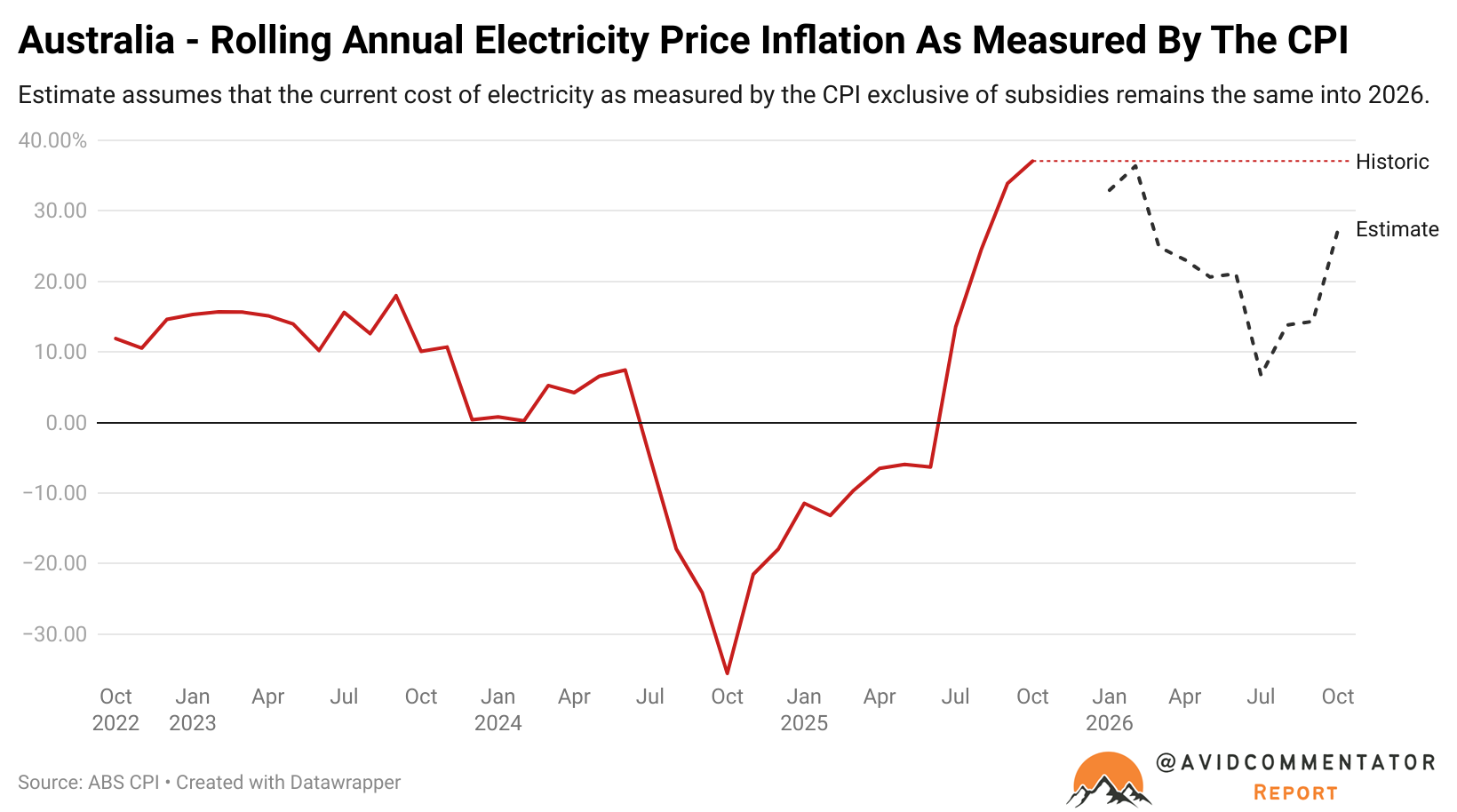

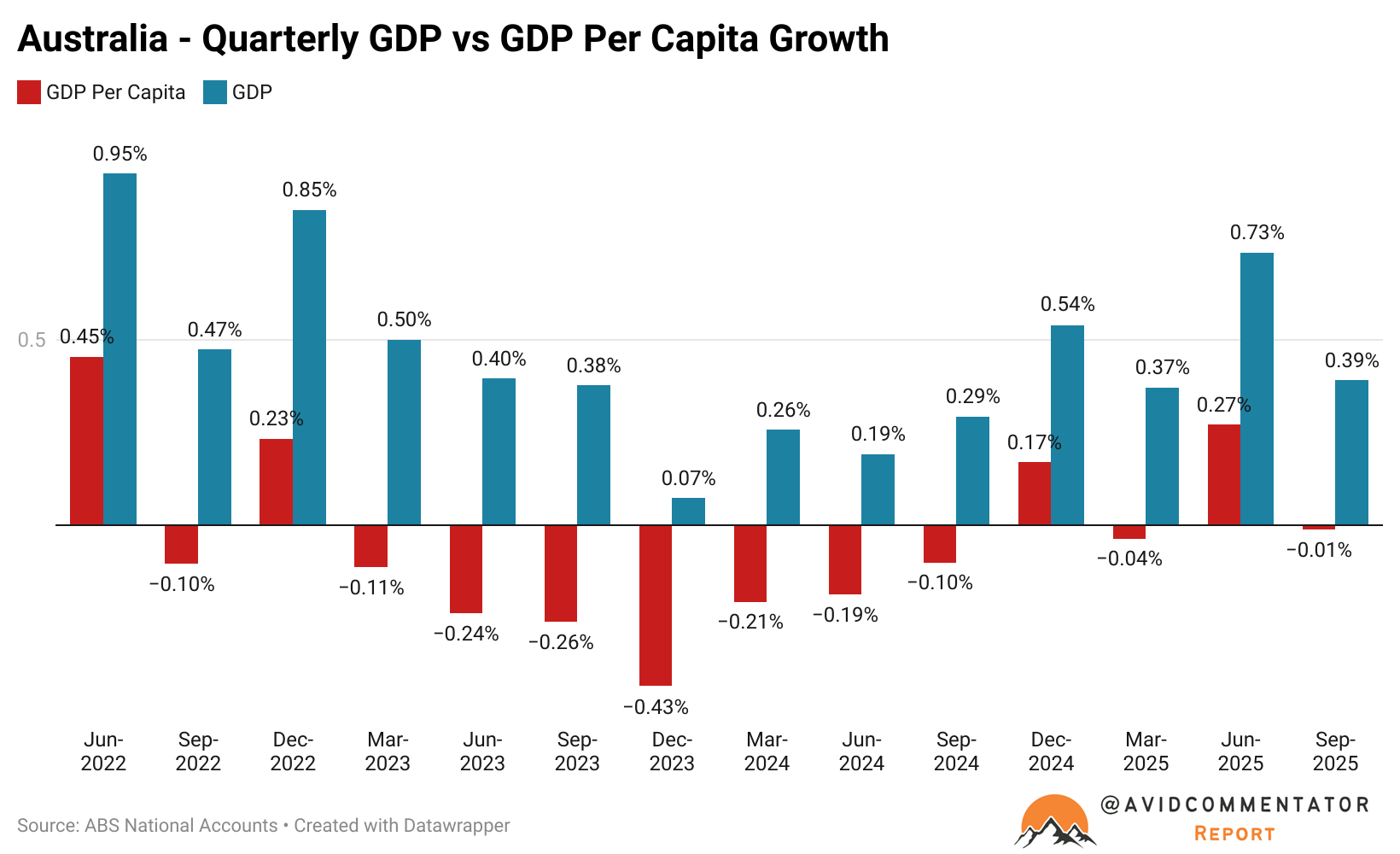

Amidst resurgent inflation after excluding the impact of the roll-off electricity subsidies, economists are increasingly examining exactly what has gone wrong for the economy to once again be struggling with inflationary pressures even as broader growth remains anaemic.

In the words of independent economist Chris Richardson, speaking with the ABC recently:

“Inflation isn’t back because of what is or isn’t happening to taxpayer subsidies for things like electricity”.

“Inflation is back because, even though the Australian economy isn’t travelling fast, its clapped-out engine is already moving faster than we can safely travel”.

“With our engine clogged by poor productivity, we’re already back where we were a while ago—with inflation bouncing as too much money chases too little stuff”.

“There’s no easy solution to that”, Richardson said

Richardson is correct; the issue stems from basic supply and demand, and this imbalance is detrimental to the overall economy.

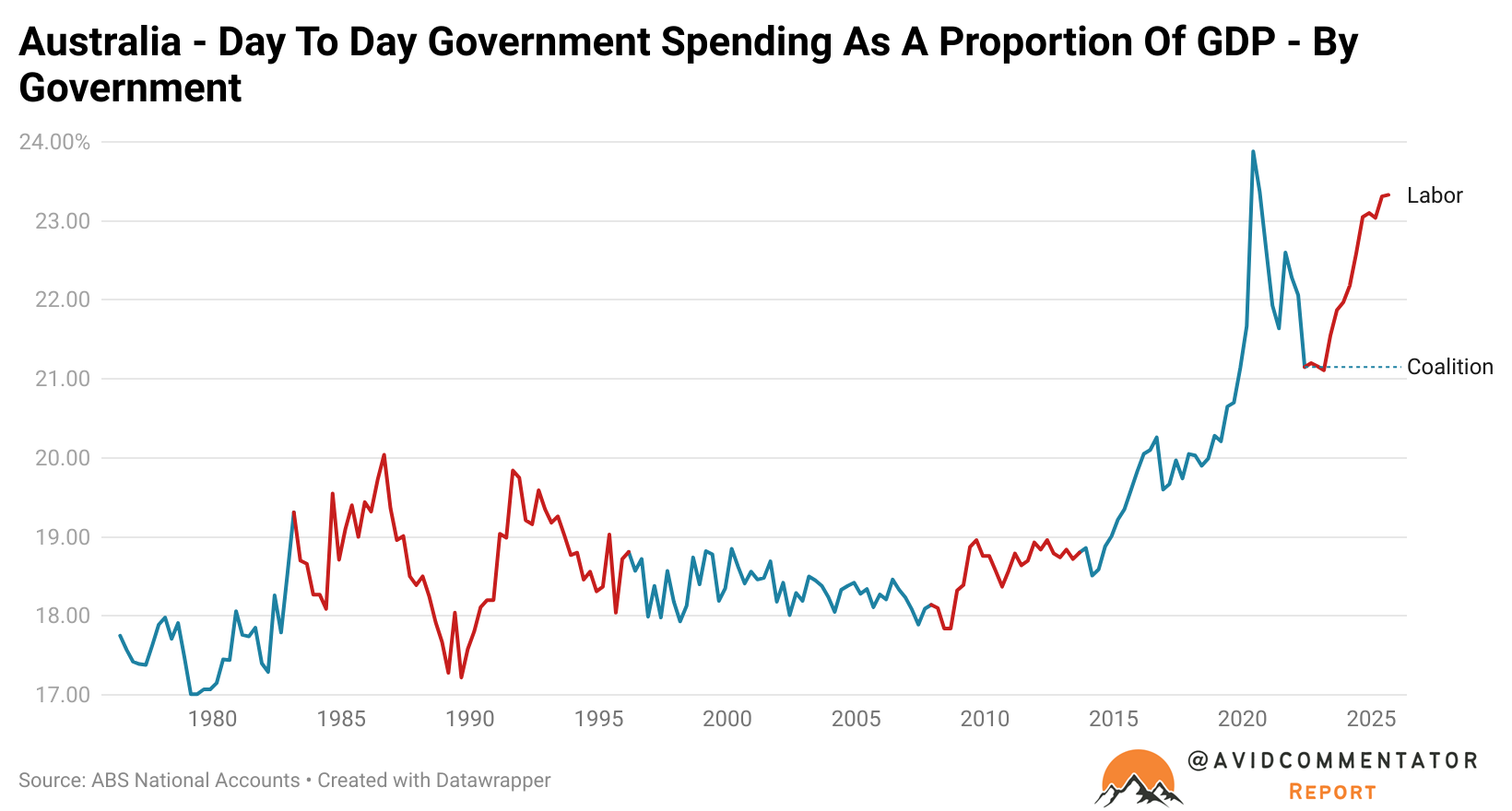

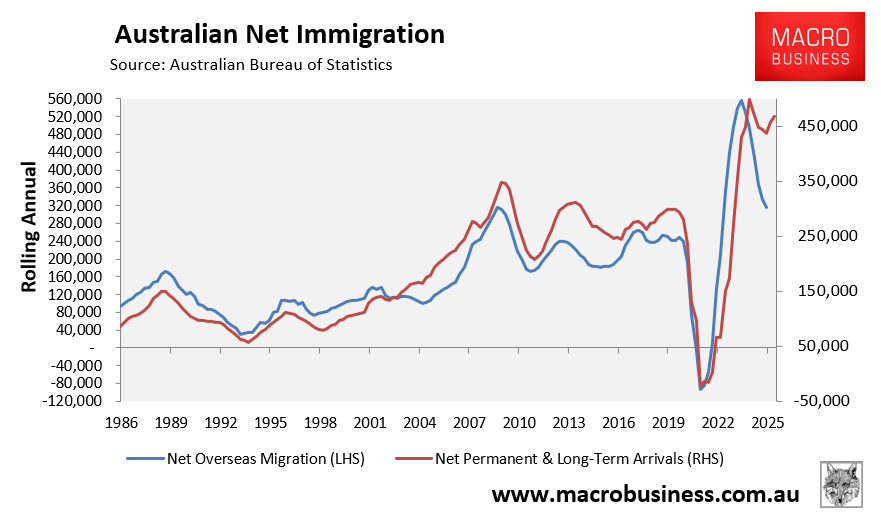

Two of the major drivers of the demand are government spending and high levels of immigration.

According to the latest ABS National Accounts data, day-to-day government spending as a proportion of GDP is currently at the second highest level on record.

It is eclipsed only by the absolute height of the pandemic, when billions of dollars a week were flying out the door to support an economy in lockdown.

The impact of the current path of government spending led HSBC to remark in a recent note:

Meanwhile, still elevated levels of net overseas migration continue to add to aggregate demand. Yet strangely, there has been no robust response from the market sectors of the economy to deliver more supply.

According to the latest ABS Labour Account data, the number of hours worked in market sectors has only grown by 0.04% since June 2023.

This is really quite a striking set of circumstances if you think about it.

It means that in aggregate the market sector activities of stocking shelves, delivering goods, unclogging drains, and building homes has only added a handful of hours, despite the size of the population continuing to rapidly expand.

The Albanese government effectively bet on a strategy of supporting the economy through additional spending and higher migration, delivering a manageable increase to inflationary pressures.

In reality, a further rise in interest rates may be required to tame inflationary pressures.

All that being said, the Albanese government did get reelected, so perhaps the strategy was successful after all.