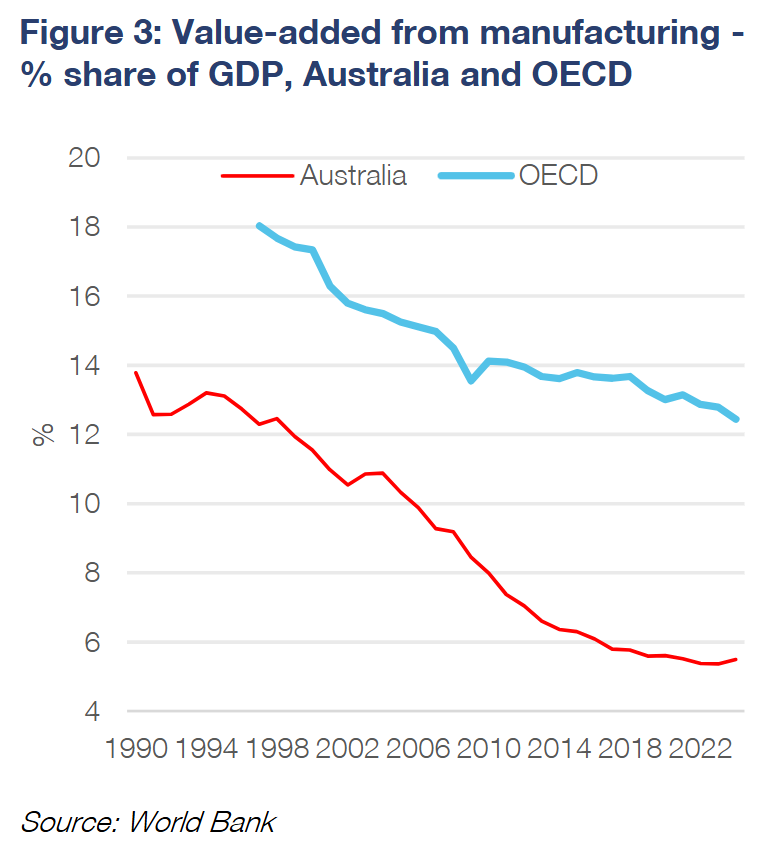

Over the last 35 years, the contribution of manufacturing to Australia’s overall economic activity has declined.

While this trend is not unique to us, the reality is that Australia had a much smaller manufacturing base as a percentage of GDP than the average of advanced economies to begin with, making the relative decline all the more impactful.

According to figures from the World Bank, Australia’s manufacturing sector as a proportion of GDP is less than half the OECD average.

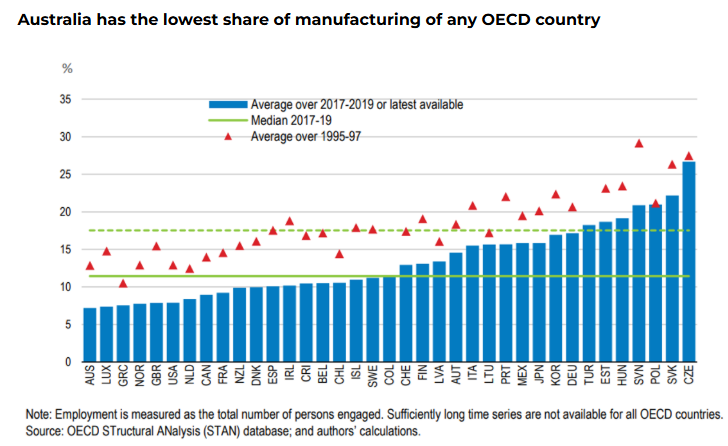

Another analysis by the OECD found that the share of GDP held by manufacturing in Australia was the lowest of any OECD nation, even lower than known tax haven Luxembourg.

While this trend is deeply concerning from a geostrategic perspective, leaving Australia extremely vulnerable to any major interruption of global trade flows, there are those who make the argument that it leaves Australia much less exposed to economic downside stemming from downturns in the global manufacturing cycle.

In terms of the direct impact, that’s certainly true; the proportion of Australia’s economy that is vulnerable to shocks stemming from global manufacturing downturns is less than half the average of advanced economies.

However, when it comes to the indirect impact of a downturn in the global manufacturing cycle, Australia is deeply exposed via its economic ties to China.

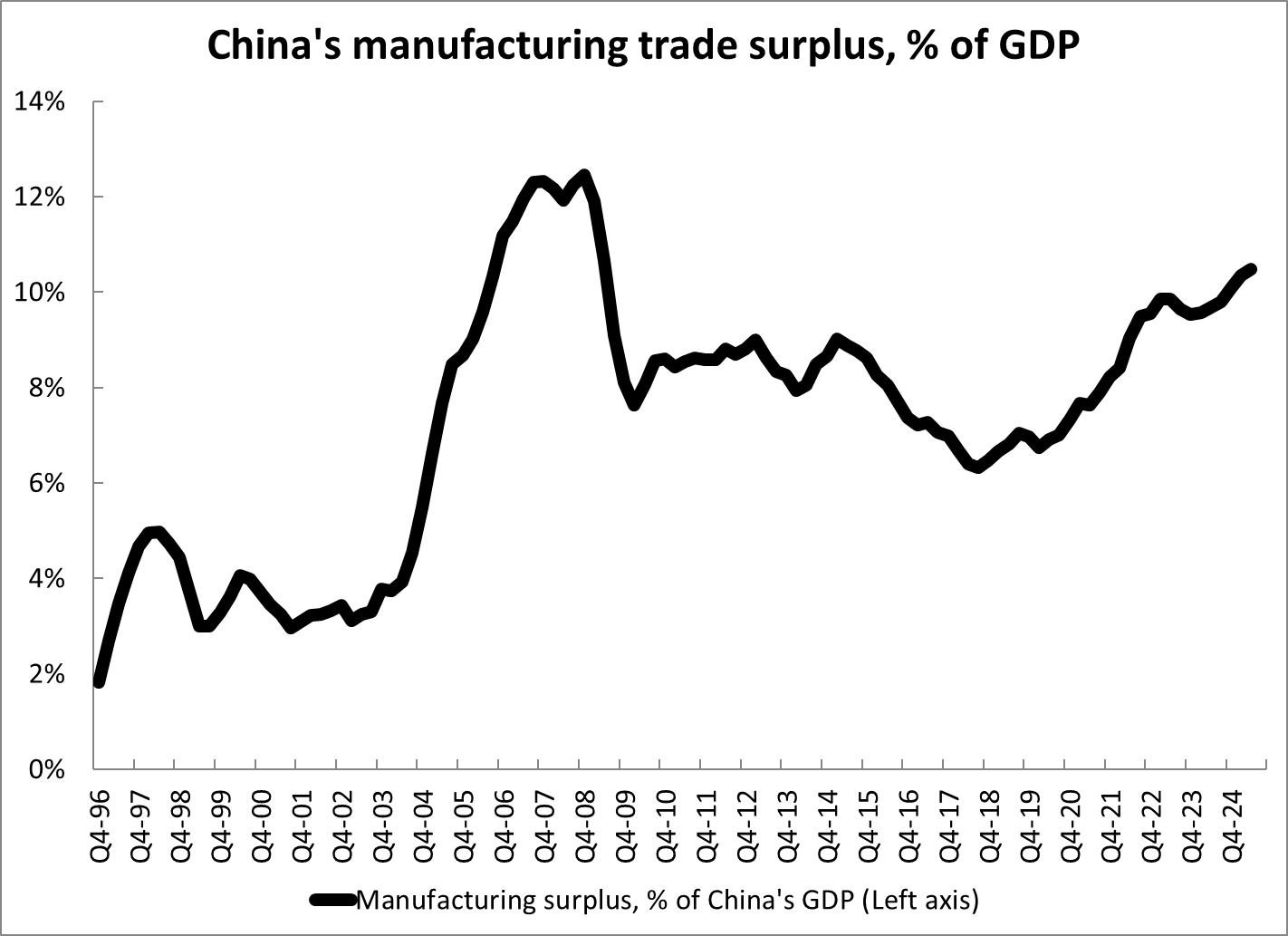

China, being the world’s factory, is the nation most vulnerable to a downturn in global trade.

According to an analysis from the Brad Setser, a Senior Fellow at the Council for Foreign Relations, China’s manufacturing trade surplus is more than 10% of China’s entire GDP.

In short, China holds the largest manufacturing trade surplus as a proportion of global GDP in the history of the world.

Enter Australia

With manufacturing accounting for more than a quarter of all Chinese GDP, a major downturn would hit the broader Chinese economy.

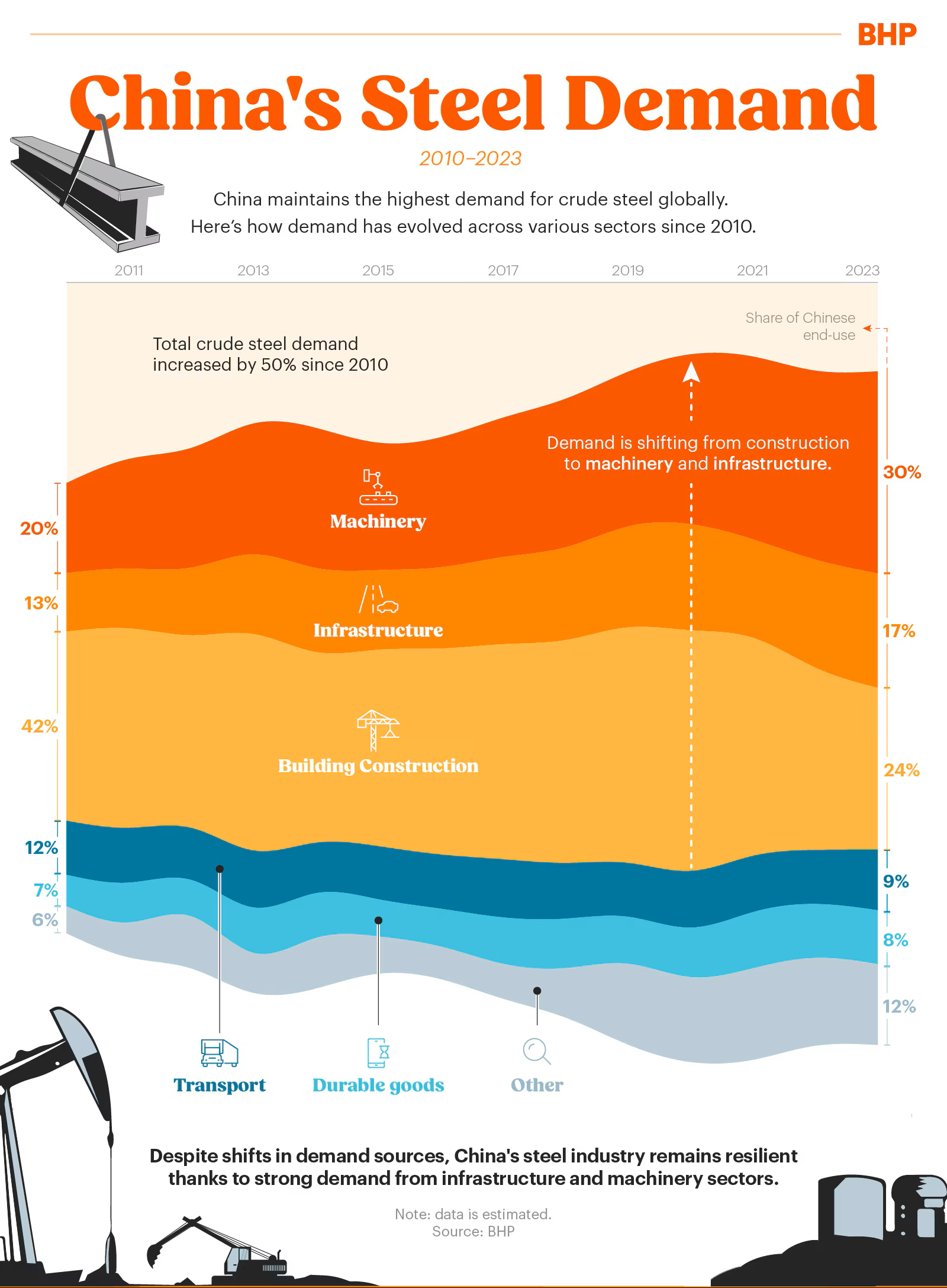

In terms of the most direct impact, more than half of the steel being consumed within the Chinese manufacturing sector is made using Australian iron ore.

According to BHP, as of 2023, China’s machinery manufacturing sector accounts for 30% of Chinese steel demand, followed by transport manufacturing with 9% and durable goods with 8%.

In terms of the longer-term impact, a squeezed Chinese manufacturing sector, which is already reliant on government subsidies, would need further government support in a scenario of a protracted global manufacturing slowdown.

This would leave fewer resources with which to pursue some of the traditional engines of Chinese growth that benefit Australia, such as construction and infrastructure building.

The Takeaway

While it’s certainly true that Australia is much less directly exposed to the global manufacturing cycle than other nations, its ties to a China attempting to come to terms with massive manufacturing capacity and the largest manufacturing trade surplus in the history of the world leave the nation deeply indirectly exposed.

Ultimately, Australia remains deeply reliant on the health of China’s industrial economy. If the Middle Kingdom begins to struggle badly, in time so will we.