Since the international borders reopened following the pandemic, a sizable proportion of Australia’s growth has stemmed from two sources: exports and government spending.

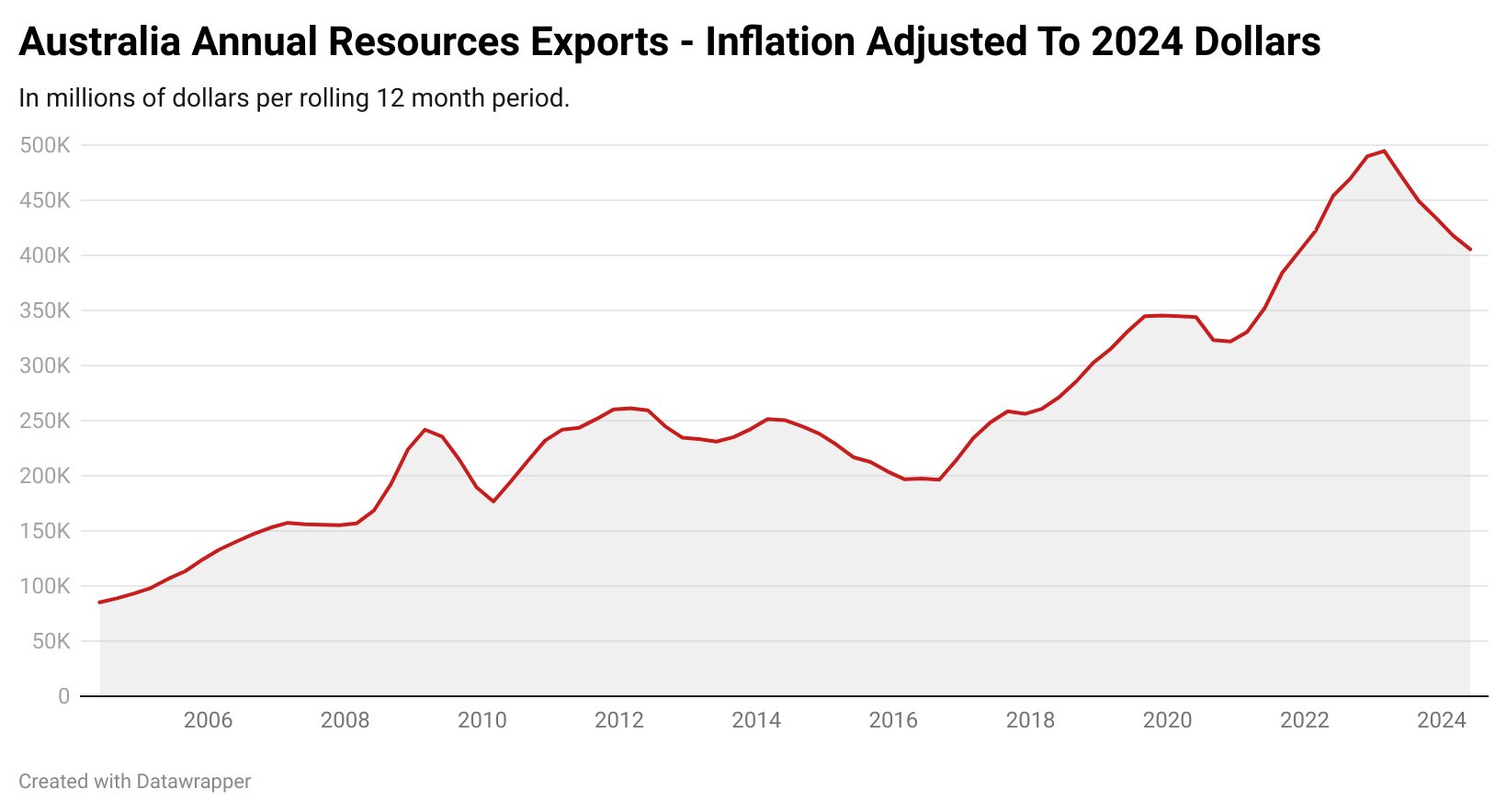

Given the impact of the war in Ukraine on commodity prices, it’s self-evident that exports would play a major role in the growth of the economy.

But there is a surprising factor that has ended up doing a great deal of the heavy lifting in keeping the national accounts in positive growth.

International students.

According to a report from the Australian Financial Review (AFR):

“Spending by international students accounted for more than half of Australia’s economic growth in 2023, according to new research.”

“Analysis of the national accounts figures by economists at NAB found education exports, which captures spending by international students living in Australia, was equivalent to 0.8 percentage points of annual GDP growth, or more than half the 1.5 per cent annual rate in December.”

Which begs the question: how do international students make such a large contribution to the economy?

All manner of everyday consumption done by international students in Australia is counted as an export.

A Big Mac? An export.

A loaf of bread from the supermarket? That’s an export.

A bus ticket? That’s an export

Rent from a landlord? That’s an export.

The Official ABS View

Here is a brief excerpt from an ABS paper on education exports on how they are calculated.

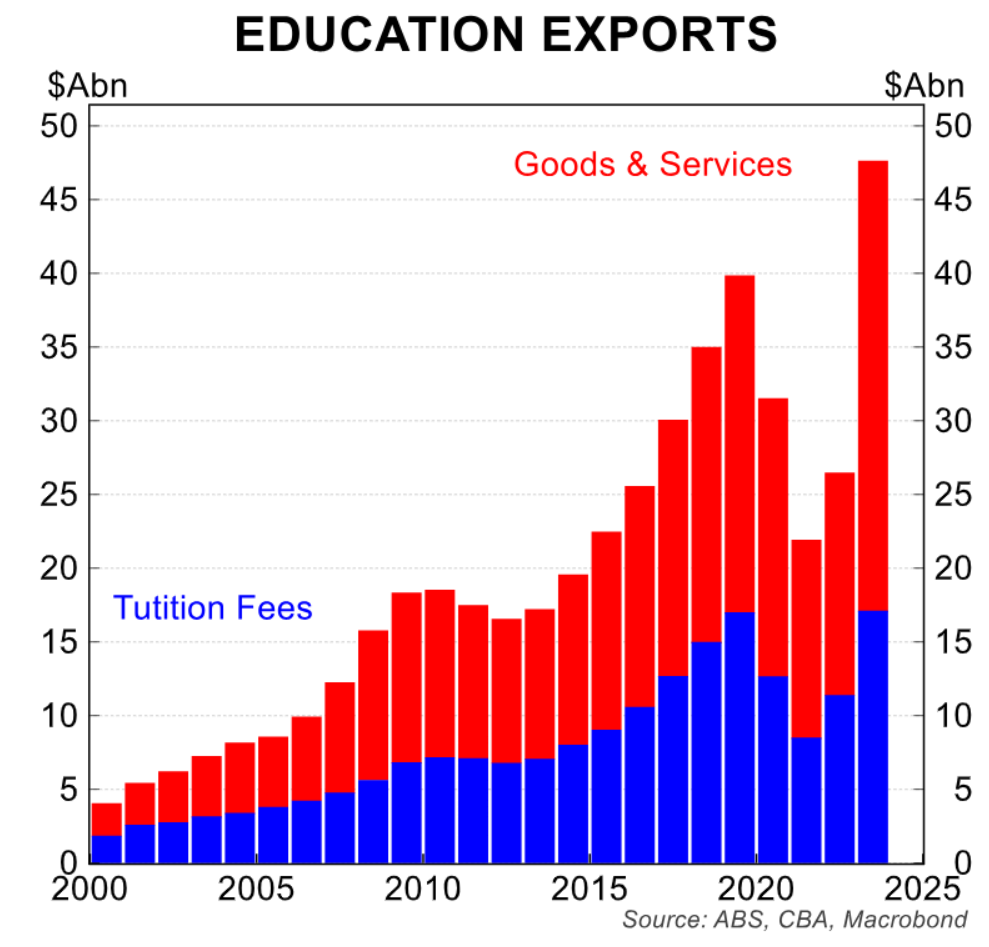

All expenditure by international students studying in Australia is recorded as an export in the Balance of Payments statistics published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This includes expenditure on tuition fees, food, accommodation, local transport, health services, etc., by international students while in Australia. This expenditure contributed $50.5 billion to Australia’s exports in the 2023-24 financial year.

The ABS also makes no distinction between what consumption is funded from overseas sources and what is funded by local employment. As they detail below.

The classification as an export of expenditure by international students studying in Australia does not depend on how the students fund their expenditure in Australia. Some of the expenditure is funded from overseas sources. While it is not possible to be precise, ABS estimates suggest around a quarter of the expenditure (around $13 billion in the 2023-24 financial year) is funded by international students working in Australia for Australian employers.

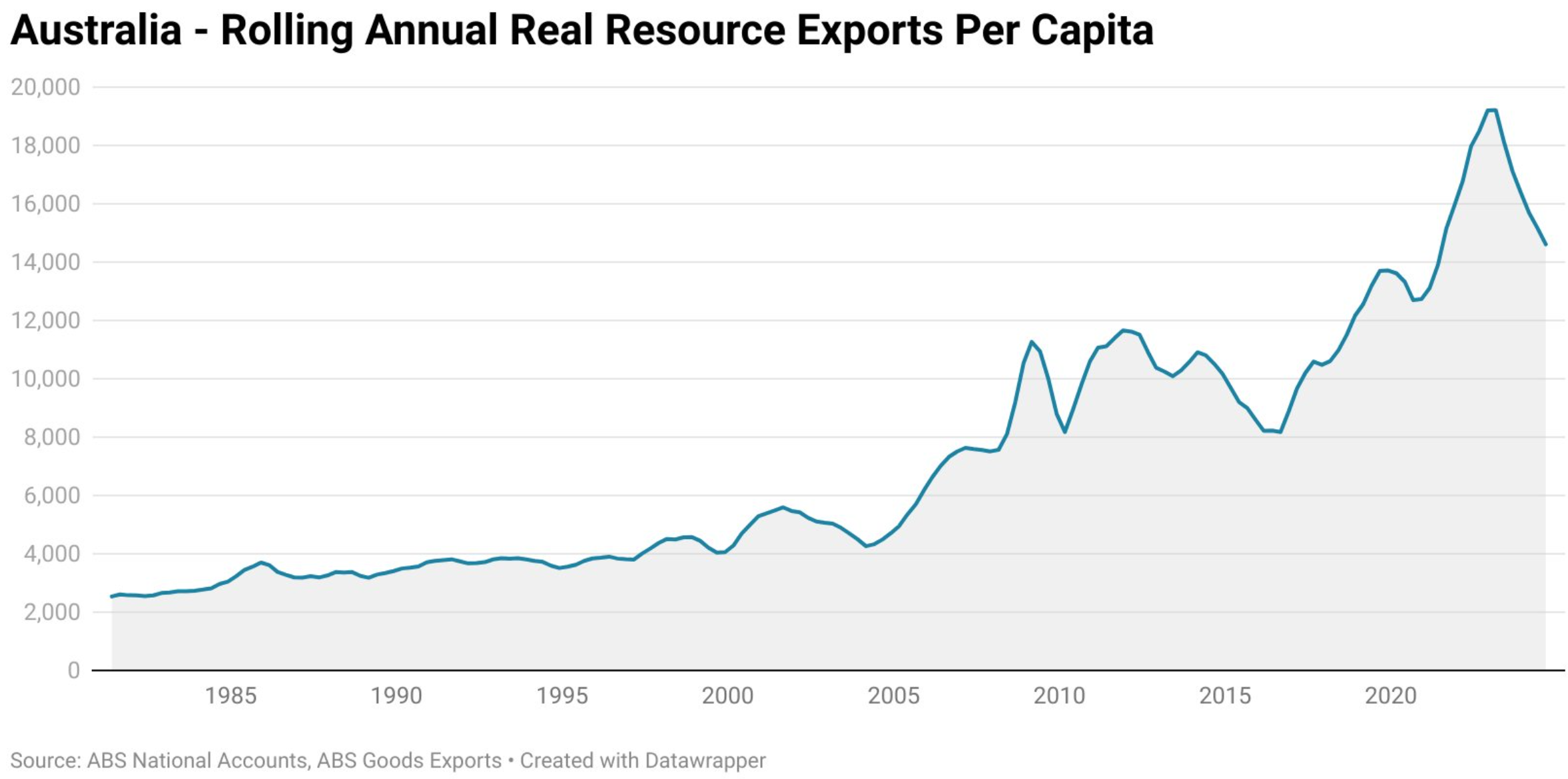

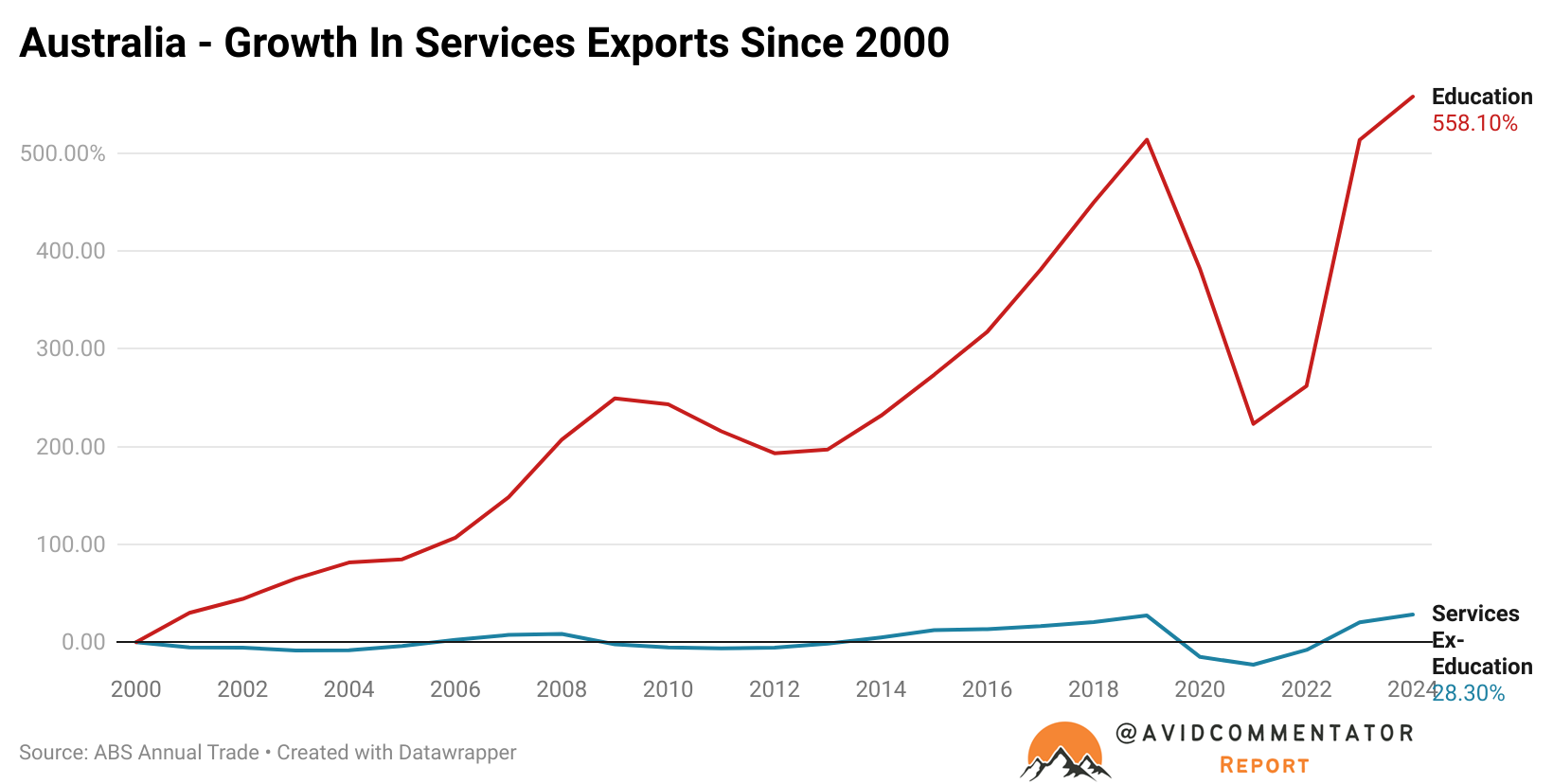

Since 2000, the total amount of annual export revenue derived from education exports has risen by 558.1% in inflation-adjusted terms. Meanwhile, service exports excluding education have risen by 28.2%.

Papering Over The Cracks

Taking a step back and looking at the economy more broadly, it makes sense why policymakers are largely heavily in favour of the international student-led growth model.

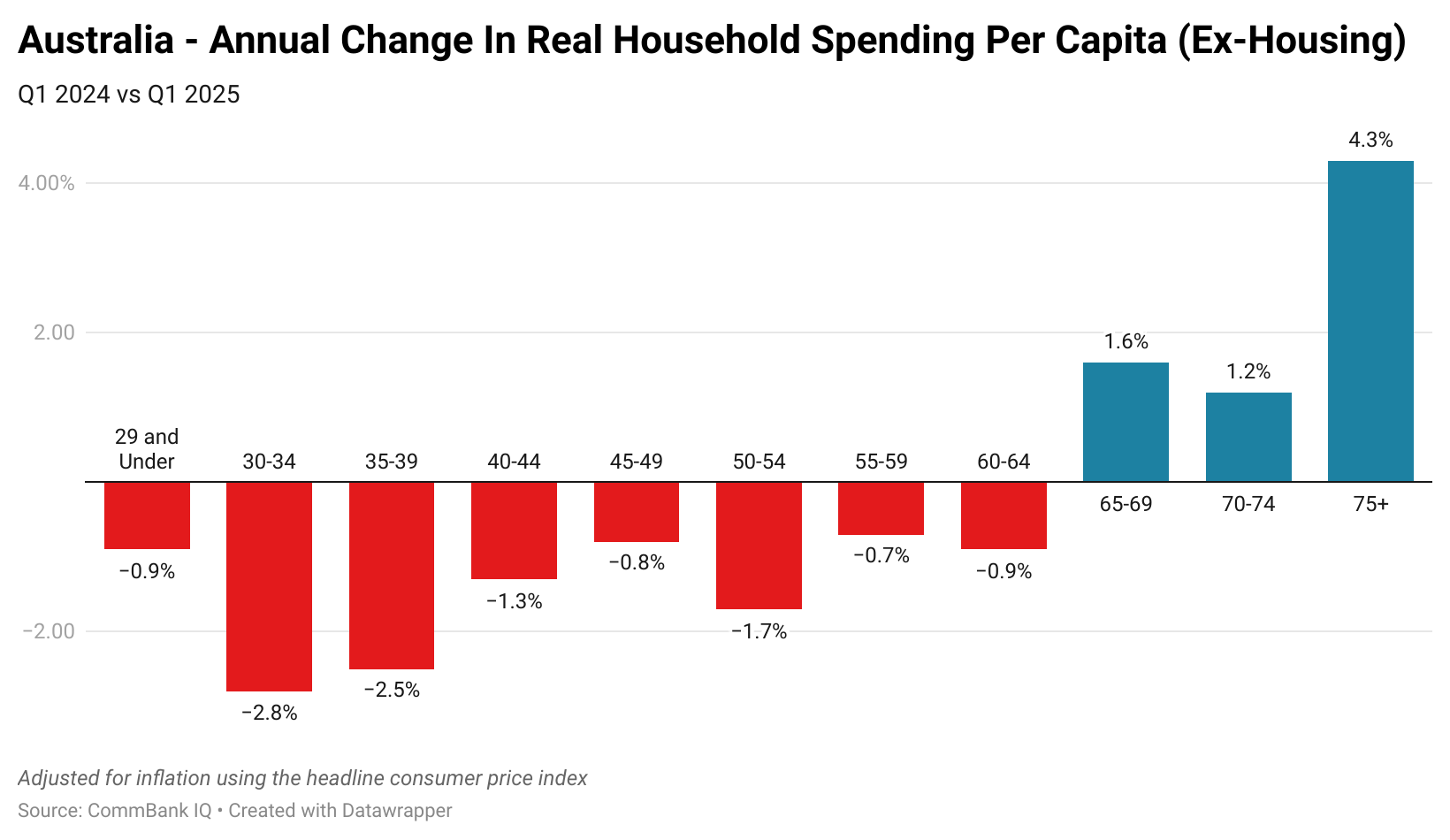

Real household consumption (ex-housing) is going backwards for all age demographics in aggregate, except those aged 65 and over.

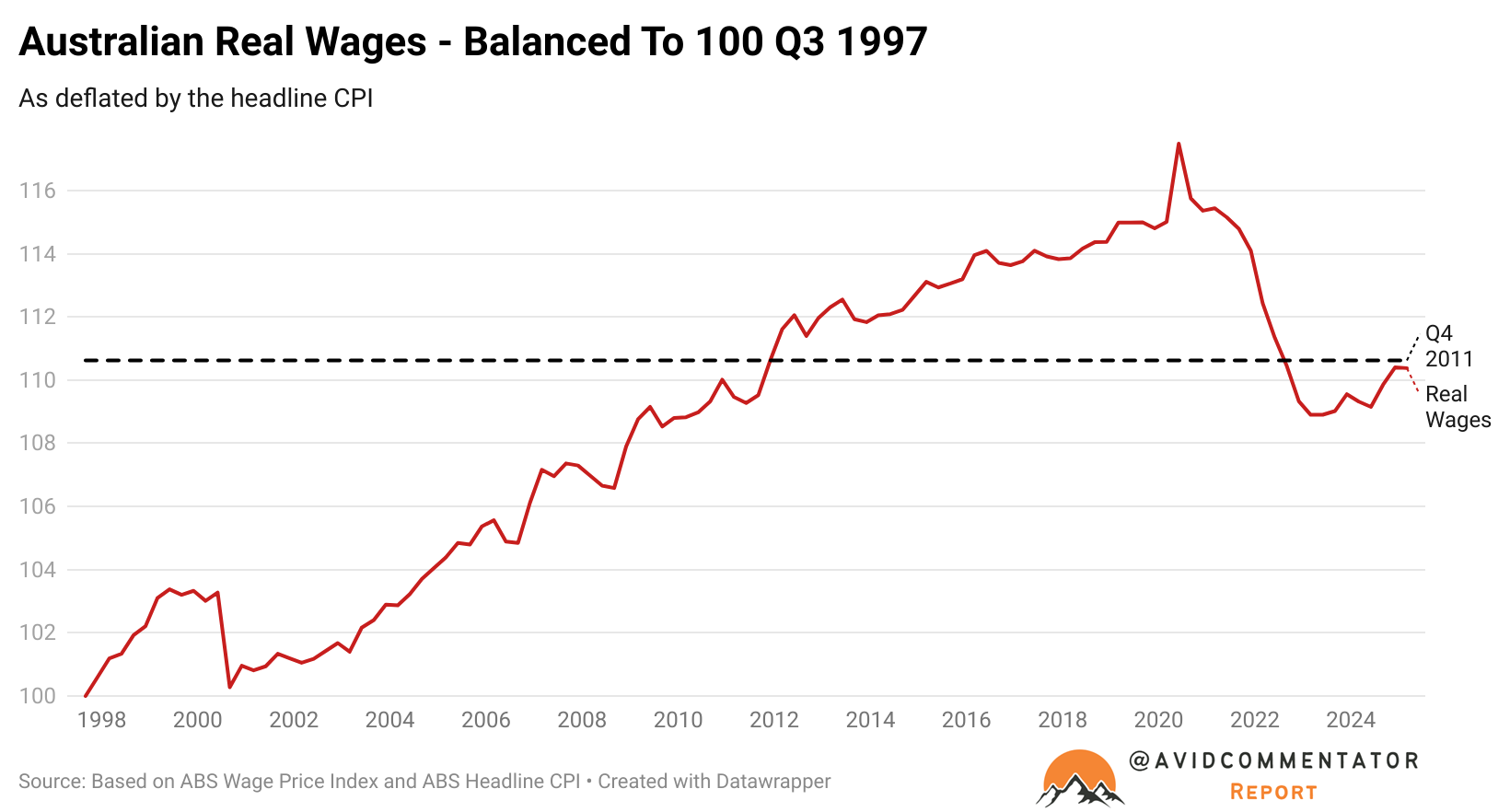

Meanwhile, real wages are currently sitting just below Q4 2011 levels and on a pathway that may take over a decade to get back to where they were pre-COVID.

The problem is, international student-led growth is materially fake and makes these local income statistics worse, given that foreign students are also a labour supply shock.

Australia’s economic growth model rests on an increasingly narrow and self-defeating base.