The issue of productivity and its impact on real earnings has been a major source of debate among Australian economists since the Global Financial Crisis.

With productivity in headline terms flatlining for the best part of the last decade, except for the lockdown and closed border-driven bump seen during the pandemic, the issue has recently surged into the political and economic spotlight.

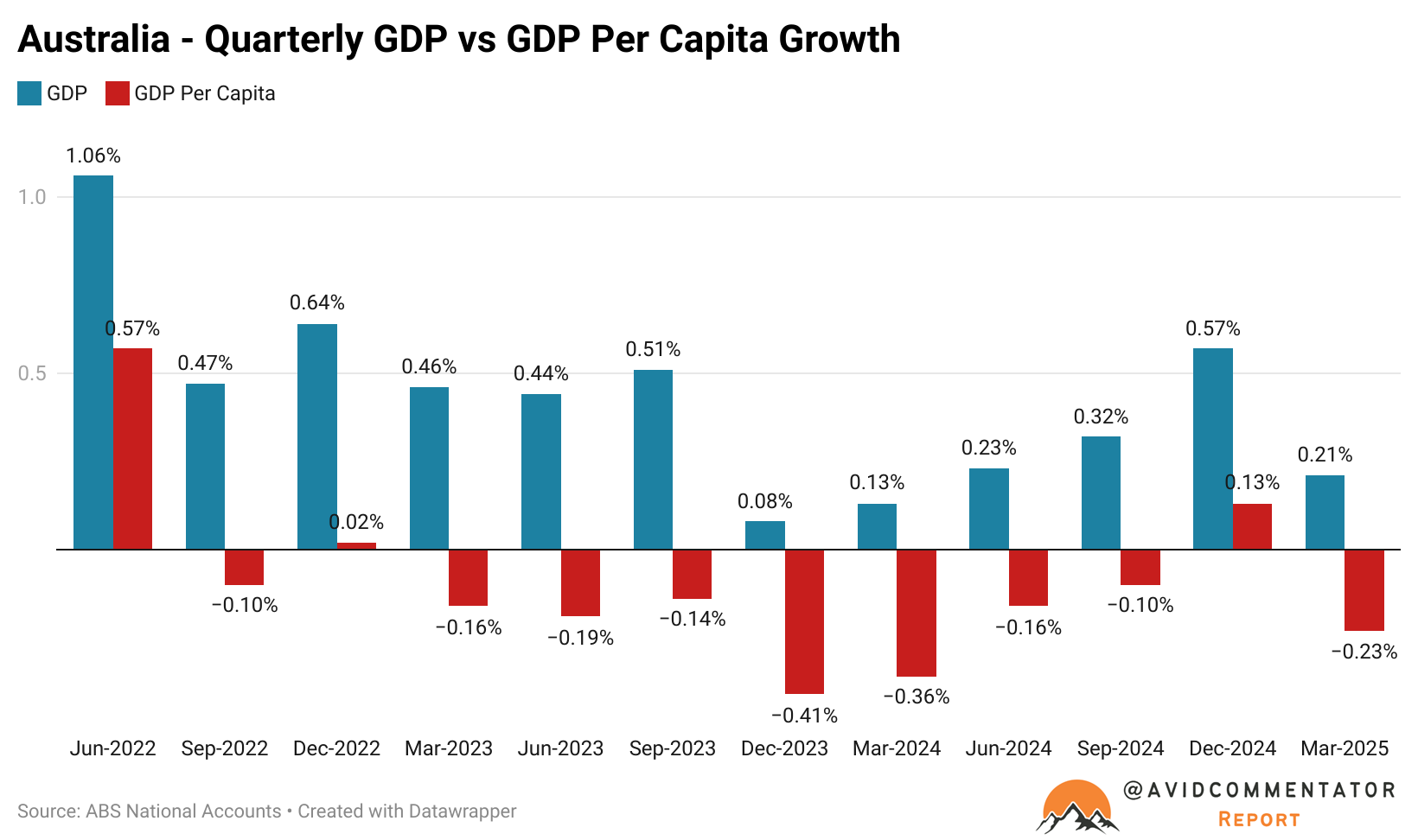

Amidst historically poor levels of headline growth and contracting per capita GDP in nine of the last eleven quarters, the Albanese government has shifted its focus to productivity growth in an attempt to reinvigorate the economy and sustainably grow real wages.

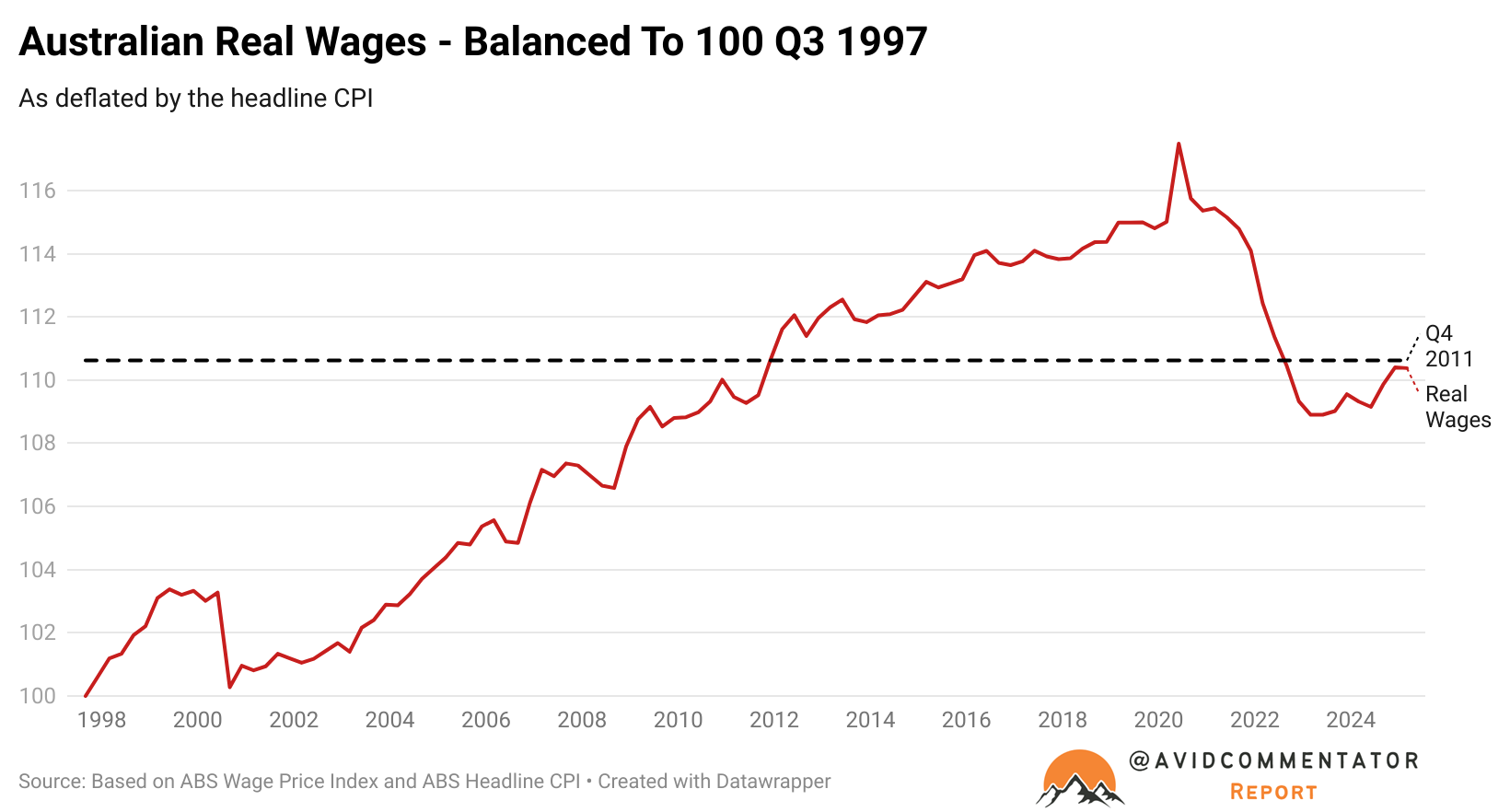

At a purely conceptual level, it’s a deeply needed change in focus, with real wages today sitting slightly below where they were at the end of 2011.

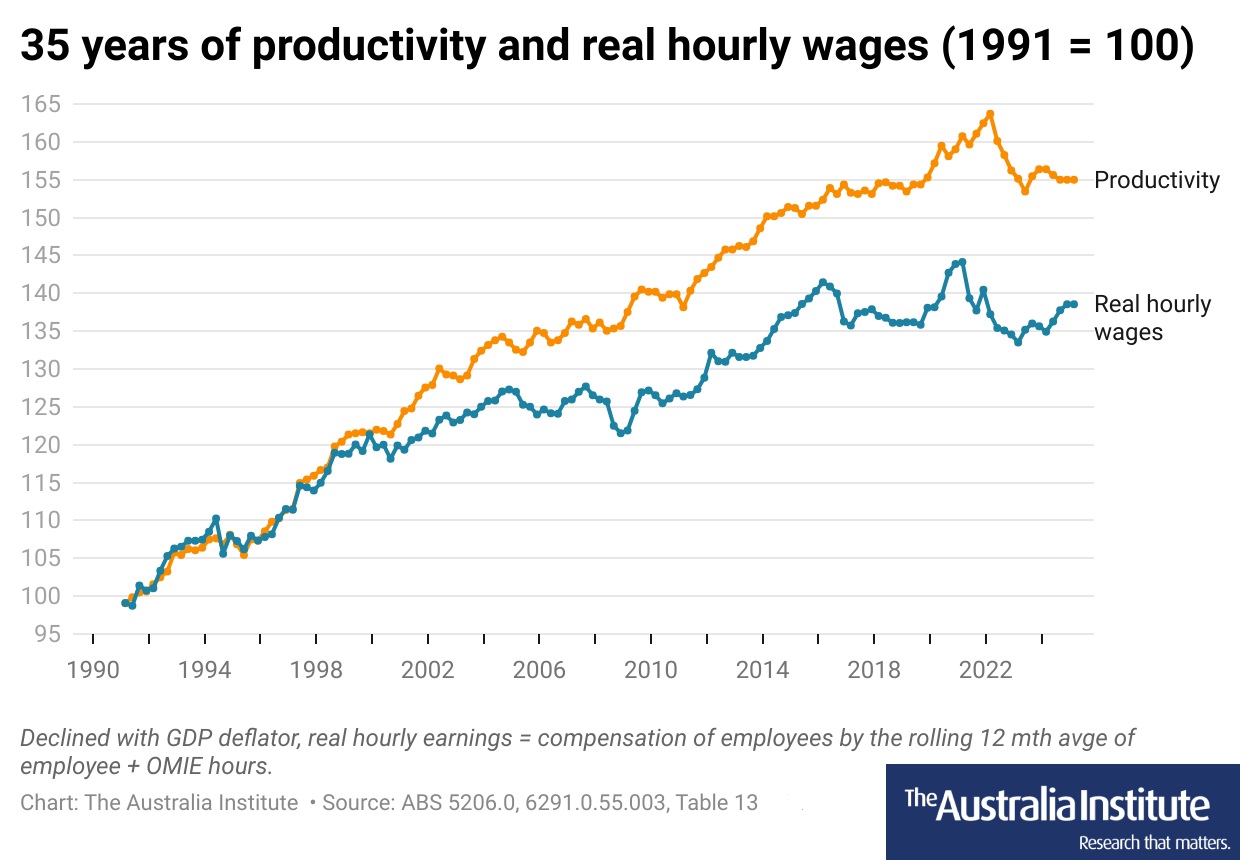

In purely headline terms, productivity growth has outstripped growth in real hourly wages since the year 2000, as shown by the graph below from the Australia Institute.

This illustration is often repeated to show that workers have not fully benefited from productivity gains in their pay packets over the last quarter of a century.

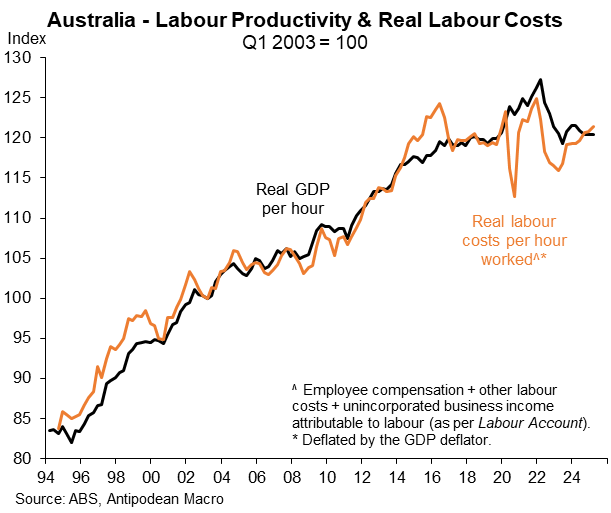

But a recent analysis from Antipodean Macro provides a very different perspective and is well worth examining.

When the focus is shifted to real labour costs per hour worked as proxy for inflation-adjusted wages and then compared with real GDP per hour worked (arguably the most prominent metric for productivity), the two measures align much more closely.

While this doesn’t change the fact that productivity growth has been abysmal for the better part of a decade, it does add an additional perspective to the current debate about productivity growth and its benefits to the average person in the street.

Going forward Australia faces a significant challenge: the government is pushing the economy in two distinct directions.

On one hand, the Albanese government wants greater levels of productivity growth to help boost real household earnings and the broader economy.

On the other hand, the government wants to keep the rise in unemployment minimal and avoid a headline recession.

The problem is the more non-market jobs (public admin, education, healthcare, and social assistance) that the government creates, the more productivity growth deteriorates in headline terms.

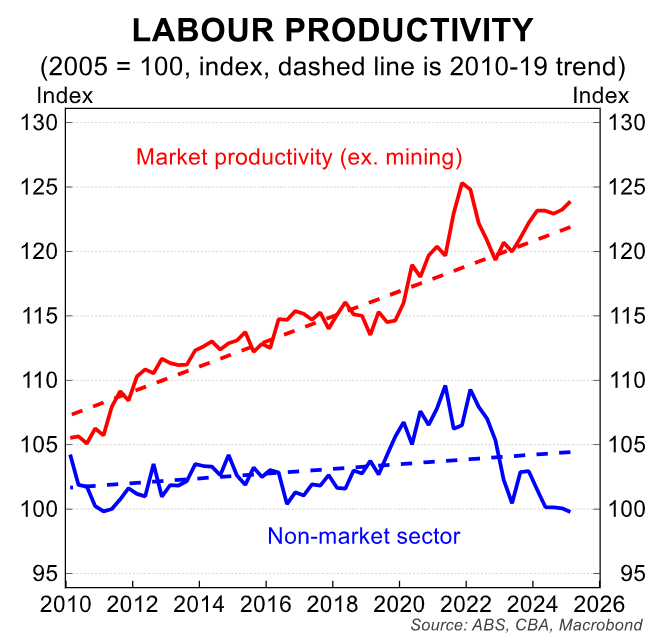

Productivity in the market sector of the economy is actually performing relatively robustly, while for the non-market sector it’s broadly flat.

If the current course continues, 2026 appears set to be the year where the rubber meets the road for the nation’s great productivity debate and where it becomes clear how viable the push for productivity growth is in an economy that has become reliant on generally taxpayer-funded jobs growth to keep the labour market ticking over.