In a recent article in ‘The Economist’ it was argued that the rise in unemployment and decreasing wage growth was the result of cuts to immigration in nations such as Canada, Britain and the United States.

“Having won elections promising to cut migration, politicians across the rich world will now have to deal with the consequences of actually doing so.

Consider the labour market first. Overall wage growth is declining across advanced economies, rather than rising as anti-migration types had expected. The unemployment rate is also inching up. In Canada it has jumped by two percentage points from its recent low, one of the worst performances of any rich country. This is not consistent with the idea that immigrants steal jobs from their hosts. Indeed, it is more plausible that some of the leaving immigrants had previously employed native workers.”

Using facts and figures, let’s unpack ‘The Economist’s’ perspective in a fact-based way and compare the narrative above with Australia, where immigration is still at record highs compared with pre-pandemic levels.

First off, the slowing of wage growth and the rise in unemployment are exactly what one would expect to see in nations that have undergone one of the largest and swiftest relative rises in interest in their respective histories.

It is, however, worth noting that in the age of ‘Burnout Economics’ where governments are acting to stimulate the economy with additional spending while central banks are attempting to rein in inflation, this is not as universal as it once was.

That being said, it’s not universal, and the government’s choice to pursue this path has little to do with immigration.

Enter Australia

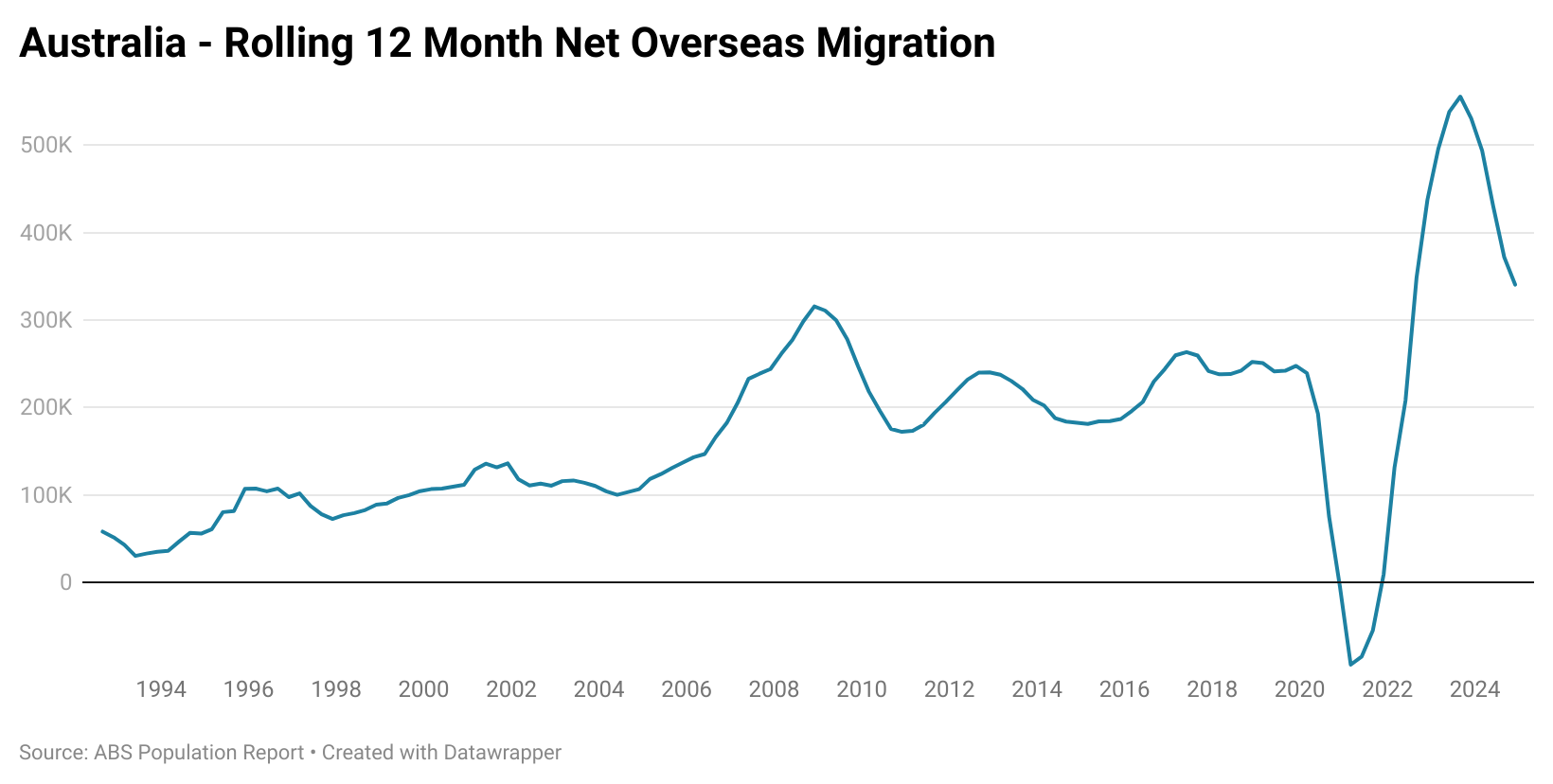

According to figures from the ABS, which cover up to the end of the December quarter of 2024, net migration over the last 12 months was 340,750 people. This is 93,130 people per year higher than its final pre-pandemic reading and 37.6% higher in relative terms.

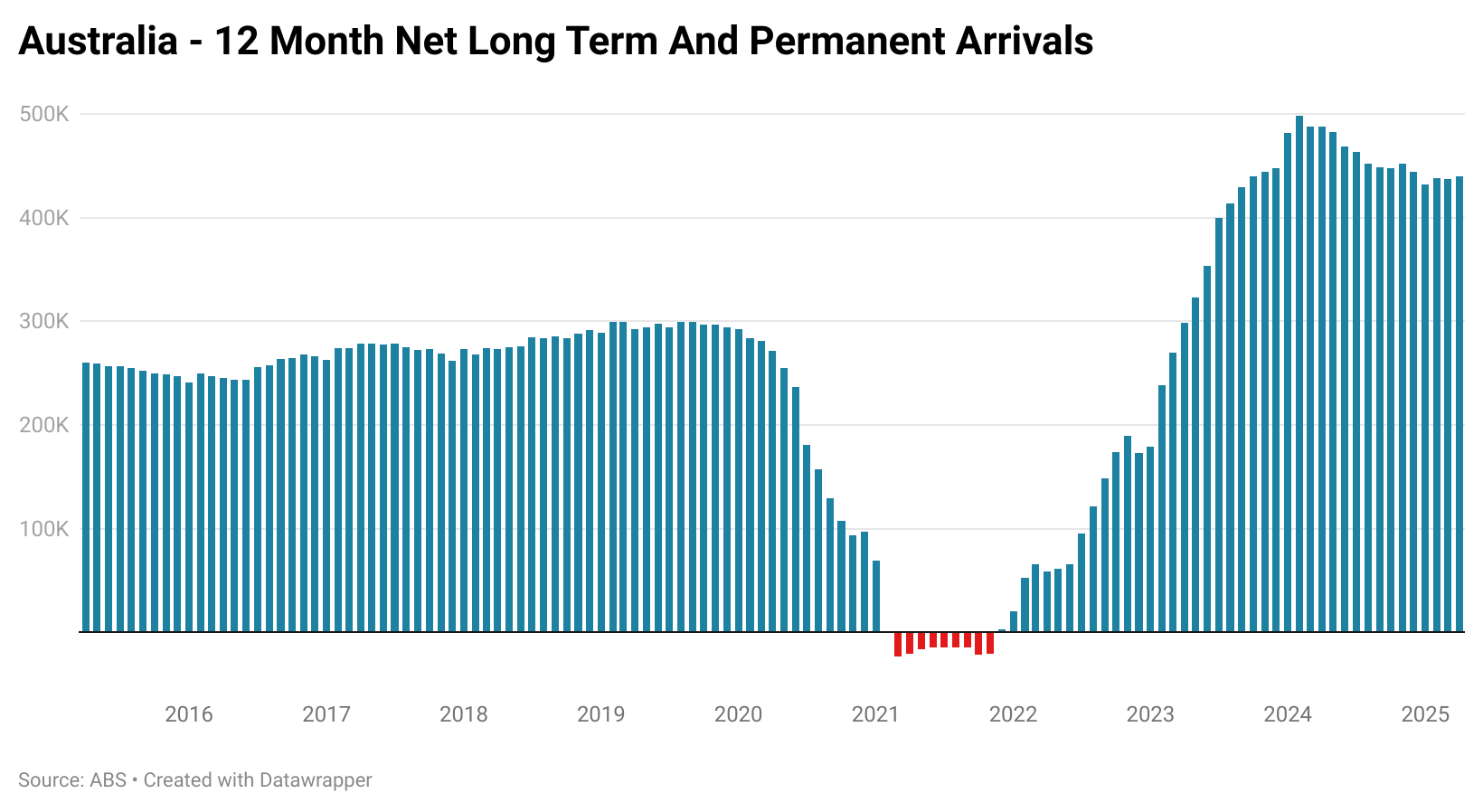

More up-to-date figures from the ABS on Net Long-Term and Permanent Arrivals (December 2024 vs April 2025) reveal that migration has likely plateaued roughly in this ballpark, with risks tilted to the upside given the reacceleration seen in recent months.

Given this state of affairs, it would be fair to conclude that immigration remains high in Australia. So, is this paying a dividend to the economy?

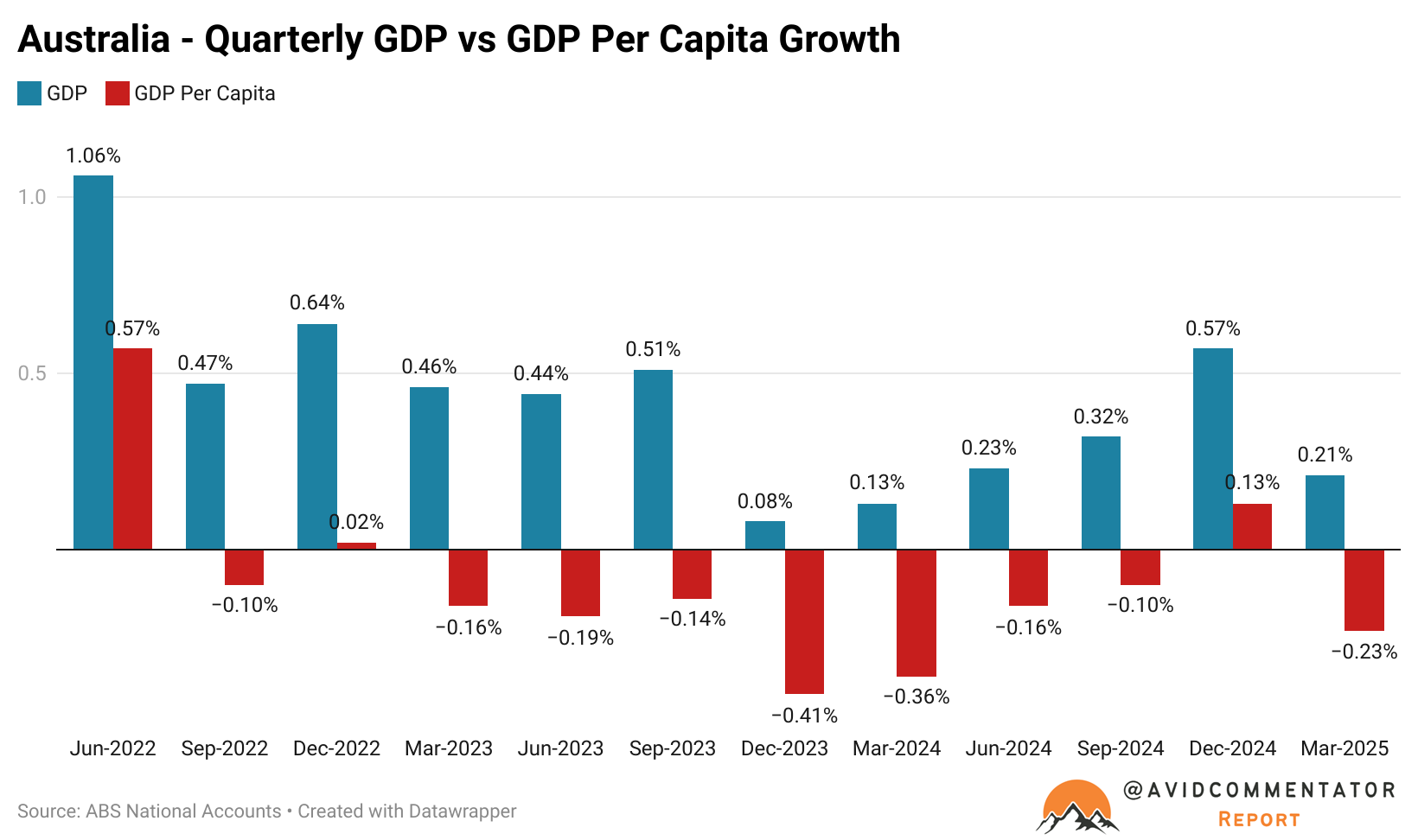

To a degree, yes. It is propping up headline GDP growth figures, despite the fact that 9 out of the last 11 quarters saw GDP per capita decline.

It is also boosting the bottom line at the federal Treasury, boosting tax revenues significantly beyond projected levels due to a larger-than-expected taxpayer base.

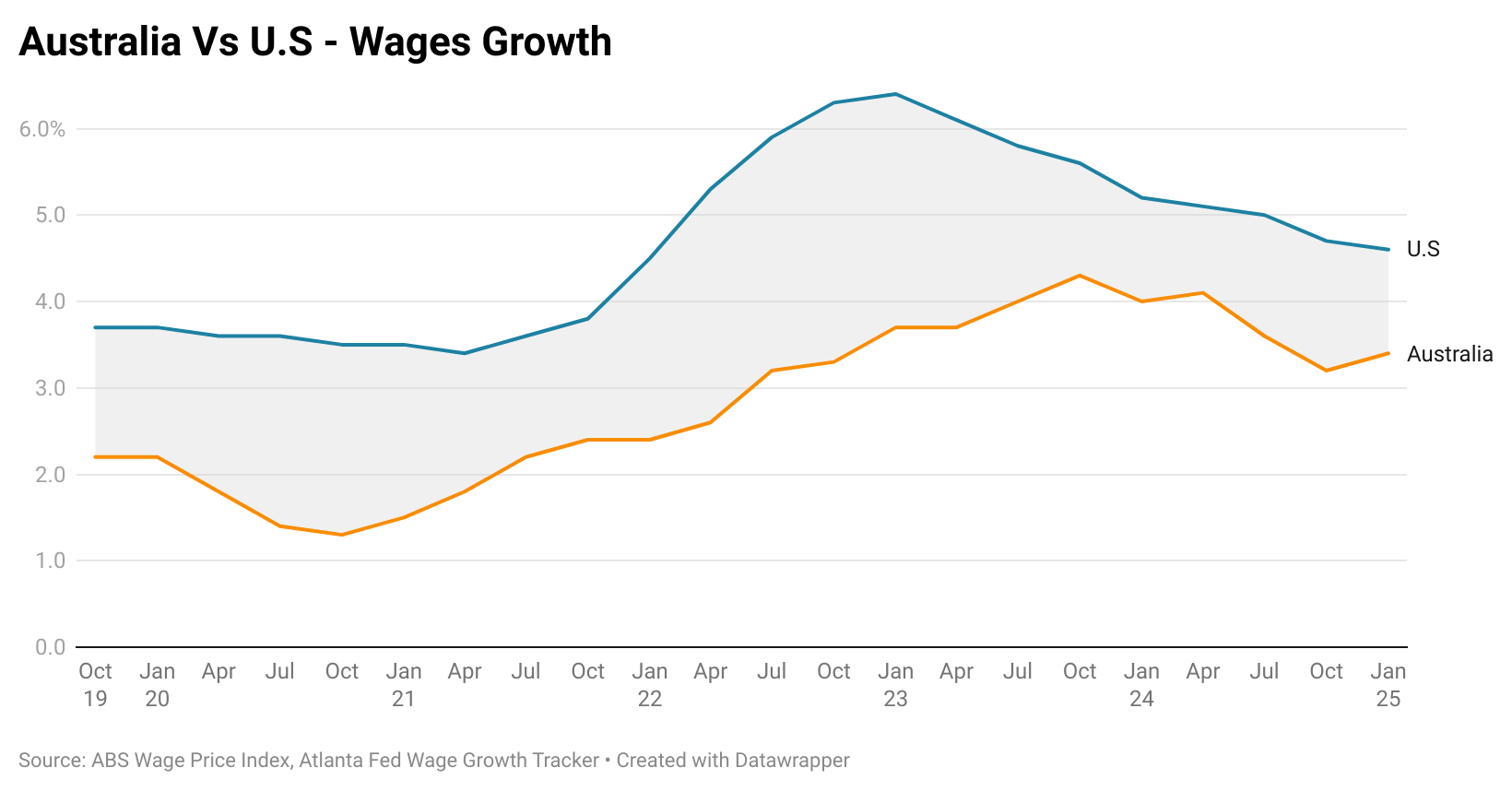

If we compare Australian wage growth with the U.S, the Americans handily emerge on top. As of the end of the March quarter, which is the latest data point available for the ABS Wage Price Index, annual wage growth in Australia was 3.4%.

Meanwhile, in the U.S the Atlanta Federal Reserve Wage Index was seeing growth of 4.6%.

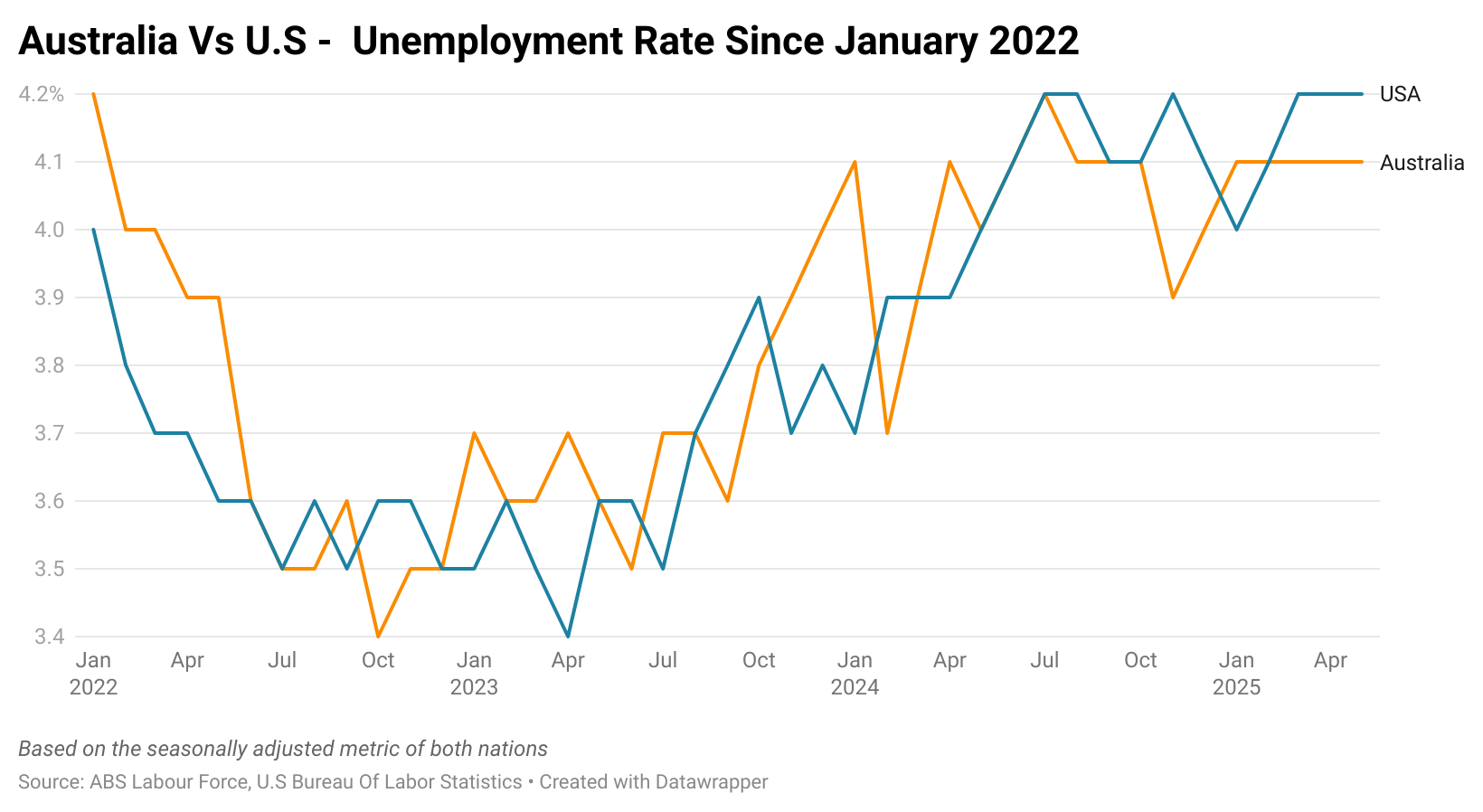

In terms of the pathway of unemployment, the broad strokes are relatively similar thus far in Australia and the U.S.

In Australia, unemployment bottomed out at 3.4% in October 2022, before rising to 4.2% in July 2024 and has since stabilized at around 4.1%.

In the U.S, unemployment bottomed out at 3.4% in April 2023, before rising to 4.2%, which is where it has sat for the last four months.

But there is a major difference between Australia and the U.S, the rise of non-market jobs, aka jobs in sectors that are overwhelmingly funded by the various levels of government.

While both the U.S. and Australia have seen the total proportion of the workforce employed in non-market jobs rise, the rise in Australia since the onset of the pandemic has been significantly larger.

The Takeaway

In Australia, a high immigration strategy is still very much being pursued, yet it faces many of the same issues that other economies with much lower levels of migration face.

Given the level of employment growth in non-market sectors being undertaken largely by government, one would expect Australia to be performing significantly better than its peers, yet it isn’t.

In reality, despite a level of immigration well over the pre-Covid record high, the parts of the economy and the level of hours worked in the market elements of the economy (all sectors excluding public administration and safety, education, healthcare, and social assistance) are lower today than they were in June 2023.

Ultimately, Australia is showing similar signs of a deteriorating economy to other nations, even though immigration remains high anthe d government is doing its darndest to prop up the economy and labour market.