Hellbourne is Australia’s first version of Mega-City One. The sprawling helltropolis of the Judge Dredd comics describes a crush-loaded future of base humanity, scrambling over one another like spifire grubs for survival.

Twenty years ago, Melbourne was a cheap and thriving creative center with excess infrastructure, booming multicultural success and a lifestyle to burn.

Today, it is crush-loaded and war-torn, dogged by machete-wielding gangs, marauding e-bike possies that humiliate police regularly, too expensive for artistic foment, and carrying a chip on its shoulder so large that a kind of sunken, pretentious hostility is the overriding sentiment.

Hellbourne crime is severe and spreading. A decade ago, Sydney had similar crime statistics figures for burglary, car theft, theft from cars, and retail theft a decade ago. However, the number of crimes across these four categories in Hellbourne increased from 131,140 in 2015 to 176,729 in 2024, while in Sydney the same incidents fell from 122,107 to just 97,553 over the same period.

Sure, it still has the greatest food on earth, if you can get to the restaurant without being threatened by a meter-long knife or being abused by the angriest people in the Western world.

To boot, public services have gone from premium to poor as the crush-loading model outstrips the permanent building site supposed to fix it.

It is run by a corrupt gang of pseudo-communists in bed with the CFMEU, who have bankrupted the state and whose only goal is to suppress free speech, such that the truth of the city’s ruination is hidden behind a thin veneer of Spring Street propaganda.

Helbourne is Australia’s first fully devolved Asian megacity, increasingly downwardly mobile to meet the slum metropolises of Bangkok, Jakarta, Delhi and Kathmandu.

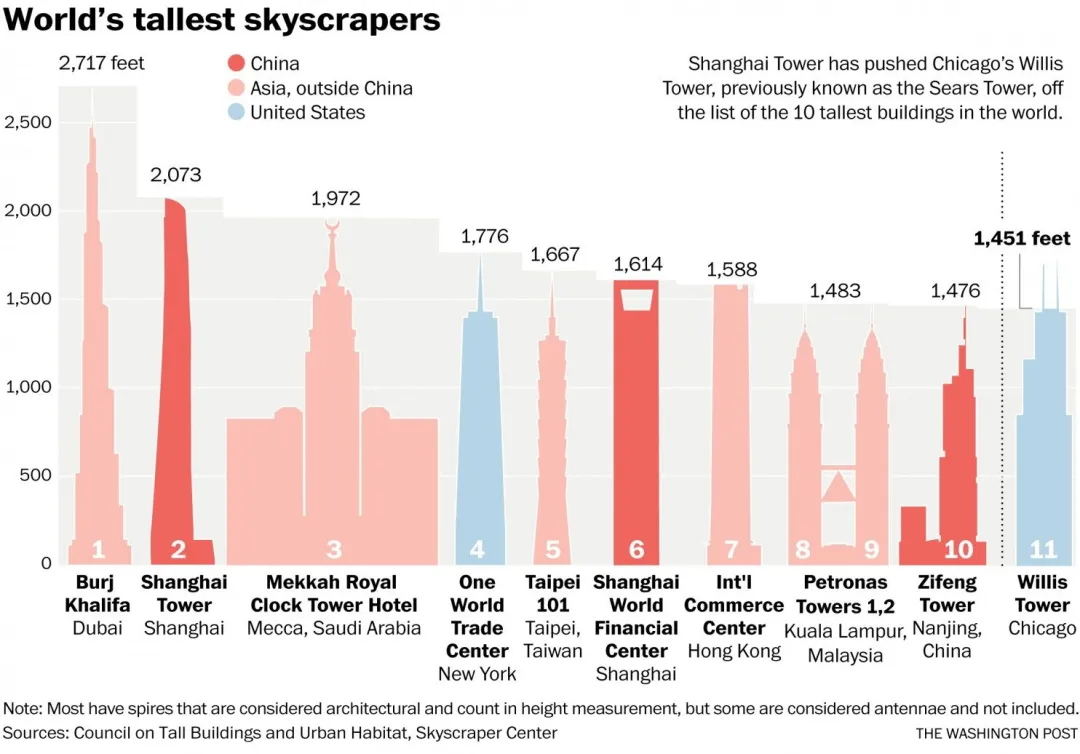

It is no surprise, therefore, that Hellbourne is, once again, leading Australia into a new downturn, with the Skycraper Index sending its prophetic warning.

The Skyscraper Index is one of those marvelous indicators that pops up now and again to make an excellent point:

It’s more apocryphal than it is scientific, but it is nonetheless indicative of overextended economic models in the final throws of exuberance. Bloomberg.

Four weeks before Melbourne entered lockdown in March 2020, a group of councillors gathered in the city’s Town Hall to back a proposal for the tallest structure that Australia had ever seen, one that would see a spiraling green garden wrapped around a 365-meter skyscraper.

The developers — a young married couple with ties to well-connected Malaysian families — were hailed as nothing short of revolutionary during the meeting. Councillor Nick Reece, who has since been elected as the city’s Lord Mayor, said that the “relative newcomers” to Melbourne were poised to deliver the most ambitious project the council had considered in its more than 170 year history.

Five years on, after buyers paid deposits for 80% of its planned apartments, the A$2.7 billion ($1.7 billion) project still doesn’t have a builder. The Melbourne-based developer Beulah, co-founded by Adelene Teh and Jiaheng Chan, was caught out by soaring construction costs in the wake of the pandemic, and creditors owed more than A$5 million have taken action to recover their debts.

In one of the most prominent examples yet of Australia’s building crunch, the millennial developers’ ambition went stratospheric, it turns out, at the worst possible time. Beulah has now engaged Jones Lang LaSalle Inc. and KPMG to scout for new investors, partners or a potential buyer of the site in Melbourne’s Southbank district, where construction is yet to start.

Amusingly, in the usual dark way, the answer here is simple. Australia’s building cost crunch emanated from two major sources.

First, the electricity shock thanks to gas cartel war profiteering. Second, stuffing in migrants at such a furious pace it created a rental price shock.

These two sent interest rates mad, rendering building entirely unprofitable and crashing the sector.

The answer is to smash the gas cartel and slash immigration.

Only then will building become viable once more as input costs fall with rents, pulling down interest rates while driving up capital values.

An even better outcome would be to abandon the failing immigration-led, labour market expansion model that has destroyed Hellbourne and return to productivity-based economics.