Labour economists are on the march.

While the RBA currently views the labour market as beyond so-called “full employment” and adding to inflation, Professor Borland said conditions were likely far weaker and supported by bumper growth in so-called non-market jobs that are predominantly funded by the taxpayer.

“Conditions in the labour market may soon be worse than they should be, if they are not already in that position,” he said, adding the circumstances did not warrant the RBA keeping the cash rate at a 12-year high of 4.35 per cent.

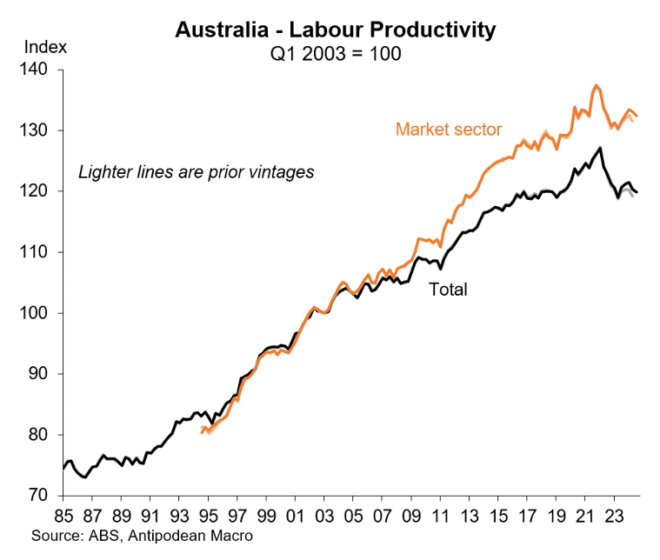

The growing share of government-aligned employees in the workforce has been a trend of the past two decades. However, jobs in health, education and the public service have surged in the past two years, climbing to more than 31 per cent of total employment.

Further indicating weakness in the jobs market was the current level of wages growth, which Professor Borland deemed was not excessive, as government-aligned jobs had a “built-in protection” that stopped them from generating inflation. Despite the economy’s run of anaemic productivity growth, Professor Borland said the trend was due to “transitory” changes in the jobs market, even as the elevated unit labour costs – the difference between productivity and wages growth – raise concerns for the RBA.

“Trying to counteract the impact of labour productivity on unit labour costs therefore runs the risk of jumping at a shadow,” Professor Borland wrote.

Damn right. Why is the RBA focused on productivity at all? It’s good to pressure the government for reform but that is completely different to setting the cash rate based upon it.

Productivity is a structural and political issue, not monetary policy input.

More at AFR from Ross Garnaut.

…missteps in monetary policy also played a large role in the seven years of underperformance before COVID-19. After 2013, the RBA kept interest rates higher than other developed countries, even though Australia’s economy was weaker. Unemployment stuck at over 5 per cent and underemployment soared. Record rates of unskilled migration put downward pressure on wages. Inflation was mostly below the target band.

…Vines and I focus on one big error in economic theory through this period and two mistakes in the application of concepts to policy.

The mistaken idea is that all that matters in macroeconomic policy is total demand so fiscal and monetary policy must both contribute to its increase or decrease. In reality, it matters a great deal whether demand to generate employment comes from lower interest rates or increased budget deficits. Too little reliance on lower interest rates and too much on higher budget deficits leads to excessive debt. And it leads to unnecessary constraints on private sector expansion.

Exactly. The RBA has exceeded its mandate. Again.